National has taken a good hard look at the issues facing New Zealand and come to a tough decision: we need to make things more difficult for poor people.

Reserve Bank governor Adrian Orr admitted to cooking up a recession on purpose, in an appearance at a select committee hearing in November last year.

“I think that is correct,” he conceded to Green MP Chlöe Swarbrick in a crypt-dry tone polished by a lifetime of banking. “We are deliberately trying to slow aggregate spending in the economy.”

A week ago, Statistics NZ revealed Orr had failed on a technicality. According to its revised figures, GDP growth only dipped 0.007%, or about $5 million, in the March quarter – equivalent to the price of a Devonport villa, one tank of petrol, or what Alan Hall got in compensation after being wrongfully imprisoned for 18 years. The sum has been deemed too insignificant to count.

Despite the sweet fiscal flatline, many people still sense something a little bit off with New Zealand’s economy. They can barely afford groceries. Mould is metastasising on the curtains of their $650-per-week rental. Air NZ sent debt collectors to repossess their furniture after they conjured a mental image of a plane ticket. In some high schools, students are having to juggle their studies with working all night to support their families. Four in 10 poor children in this country have a parent in full-time work. Meanwhile, 311 families have an average net worth of $276 million, and possess more wealth than the poorest 2.5 million New Zealanders combined.

This election, Labour has taken a good hard look at that situation and decided it needs to give people 14 cents off yams.

National, on the other hand, has surveyed the inequity burbling under the surface of our skyrocketing -0.007% GDP growth, the settings that immiserate the have-nots in order to sustain wealth and property price growth for the haves, and come to a firm conclusion: we need to crack down harder on poor people.

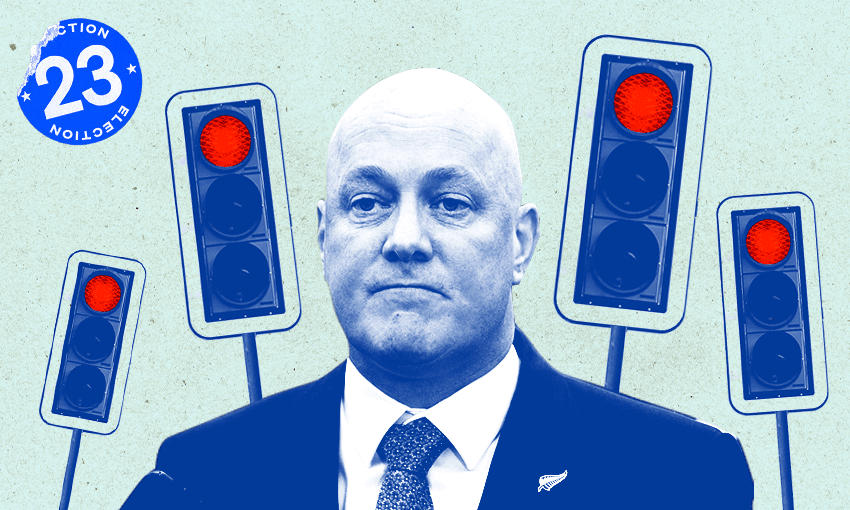

Its leader Chris Luxon stood at a strawberry farm in Kumeu on Tuesday and announced a new traffic light-coded benefit system, with those who transition through an orange warning to red being doled out punishments such as benefit suspensions or reductions. It’s hard to say what those people will do after losing their income. Presumably they’ll simply lie down and die, or carry out a ram raid to get free accommodation in Act’s new $1 billion suite of prison beds.

Some raise doubts about how much this move will address the big issues facing Aotearoa. Sanctions already exist for people on a Jobseeker benefit in our current system, despite the Welfare Expert Advisory Group finding they’re ineffective, and recent research has concluded they entrench welfare dependency by creating a cycle of desperation. Challenged to give evidence his new suite of sanctions will get people back into work, Luxon said “I think they will.”

A similarly robust method seems to have been employed on moves to address New Zealand’s other biggest problem: poor people accessing some measure of security and comfort. National’s housing spokesperson Chris Bishop says a group working with homeless people urged him to bring back no-cause evictions. It’s possible that group exists, but we know it wasn’t the Salvation Army, the Auckland City Mission, the Wellington City Mission, the Christchurch City Mission, the Queenstown-Lakes Community Housing Trust, Community Housing Aotearoa, De Paul House, Community Connections, Auckland Action Against Poverty, or Renters United.

Wellington City Missioner Murray Edridge summed up the tenor of those groups’ responses to the proposal: “I think bringing them back is a ridiculous proposition. It talks into the fact that we’re treating people who are disadvantaged in a way that’s disrespectful and undignified.”

Of course it’s ridiculous to argue just sanctioning beneficiaries and reducing their security of tenure will be enough to fix New Zealand on its own. National is also vowing to cut back benefit increases by $40 this term by tagging payments to inflation rather than wages, and to repeal Fair Pay Agreements for those who do get a job. The groups in line for a pay rise under that legislation include cleaners, hospitality workers, and grocery staff. They were once hailed as essential workers who got us through the pandemic. On the other hand, a misleadingly edited document from Business NZ says paying them more would breach international labour treaties.

In other comments to the select committee last November, Orr said “there will be a likely rise in unemployment” as a result of the Reserve Bank’s inflation-busting recession. He urged workers to adopt a low inflation mindset and avoid asking for a pay rise to match the cost of living.

Many people accessing the Jobseeker benefit will be the product of those efforts to right the economy. Some would see a certain meanness in punishing them further given their desperation is in part deliberately engineered. There could even be an argument that beneficiaries are doing heroic work taking heat out of the job market– that they’re on the ground so the rest of us can soar high on the wings of inflation within the target band of 1 to 3%.

Those arguers don’t understand: when someone’s on the ground, that’s the best time to kick them. It’s much easier than going after someone powerful; someone who actually might be the real problem.