While they reap the benefits of living in a liberal democracy, what compels those who left behind a country brutalised by the Marcoses to give them another chance? A deep-seated and insidious cynicism, argues Monica Macansantos.

At a campaign rally in my hometown for Leni Robredo, a candidate in the recently concluded presidential elections in the Philippines, I could feel a palpable sense of hope in the air – rare in a country that views politicians running on a platform of reform with scepticism, if not outright derision. Volunteers and attendees shared food and drink, exchanged smiles and words of kindness with complete strangers, and made way for each other instead of shoving people aside to secure a better view of the stage (a habit that’s common in the Philippines, and which Filipinos themselves are quite aware of).

There was a shared sense that we had finally gotten our act together as a people, consciously shedding our self-serving habits that have undergirded a culture of corruption in our country. This was because we had found a leader to rally behind, a woman whose untarnished record as a public servant and selfless devotion to grassroots causes had given us permission to believe that a better future for our nation was finally within our reach.

“Walang pag-asa ang Pilipinas” (there’s no hope for the Philippines) is a line I’ve heard from many Filipinos who have become resigned to the seemingly unending cycle of corruption and mismanagement in which our nation has been mired, even after a popular uprising ousted Ferdinand Marcos and his kleptocratic family from power in 1986. It’s the kind of resignation that I found especially pronounced in Filipino immigrants I met while living in New Zealand and the United States, many of whom would habitually deride our shared homeland if only to justify their decision to leave.

Every attempt to tackle corruption and poverty back home under the leadership of more progressive and democratic leaders was usually met with scepticism, even ridicule, by many Filipino immigrants I met. For many of them, it was silly to take tangible steps towards ensuring a better future for our countrymen, to even believe it was possible to redeem a system that was, in their eyes, irredeemably broken.

This was one of the reasons why I was shocked by the widespread support I saw for outgoing president Rodrigo Duterte from the same sceptical Filipinos who’d tell me “walang pag-asa ang Pilipinas”. For reasons I struggled to comprehend, they saw hope for our nation in Duterte’s promises as president to kill all drug addicts and fatten the fish of Manila Bay with their corpses. A good friend of mine and ardent Duterte supporter told me, when we met on the streets of Wellington, that Leila de Lima, an opposition senator leading an investigation into Duterte’s extrajudicial killings, “should just shoot herself”. I wasn’t completely sure what brought even close friends to embrace the darkness and nihilism that Duterte preached with his words and deeds, but there seemed to be, at least to me, a deep-seated cynicism that prevented these people from seeing a future for our nation that wasn’t mired in death and destruction.

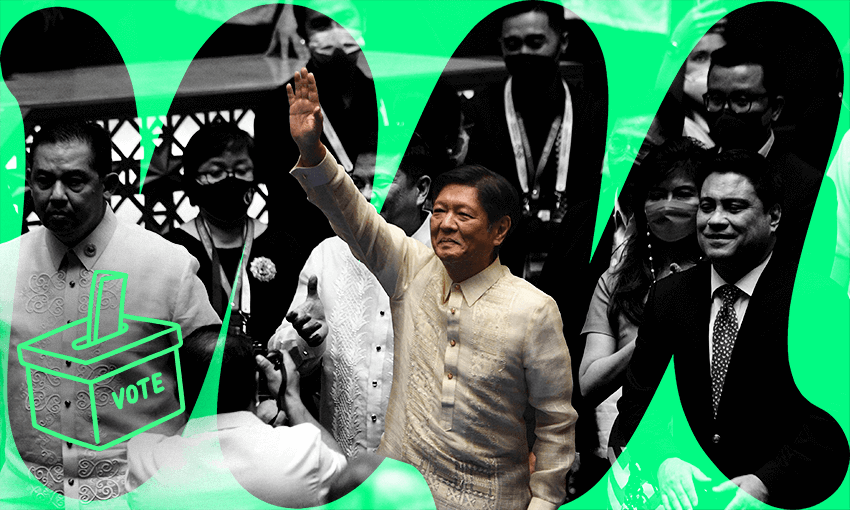

Ferdinand Marcos Jr, popularly known in the Philippines by his nickname Bongbong or “BBM”, won the Filipino overseas vote, winning by a landslide in New Zealand and losing narrowly to Robredo in Australia. I believe that this sense of cynicism that’s pervasive in Filipino immigrant communities played a role in their election of a convicted tax evader who has never acknowledged or apologised for the widespread human rights abuses committed by his family. Belonging to a society in which corruption and dishonesty are rife, thanks in part to Marcos Sr’s 20 years of kleptocratic rule, many Filipinos at home and overseas automatically expect corruption and dishonesty from their leaders.

My guess is that what makes Marcos Jr different from “everybody else”, as far as his supporters are concerned, is that he carries with him a legacy of authoritarianism inherited from his late father and celebrated by his mother (the notorious Imelda Marcos whom, I kid you not, is still alive). His supporters truly believe that this kind of government, which leaves no room for dissent when its leaders abuse their powers and holds zero regard for the sanctity of human life, will cleanse our country of its many ills. Their masochistic desire to give the Marcoses another chance makes me wonder about the full extent of their confusion and rage amid our struggles to rebuild a democracy that the Marcoses left in ruin. Their rage has become irrational and violent, allowing them to lend their unabashed support for Rodrigo Duterte’s reign of terror over the Filipino people through his bloody war on drugs.

What disappoints me is the strong support authoritarianism receives from many Filipinos in New Zealand, who left the Philippines after the Marcos family impoverished and brutalised it, and who nonetheless choose fascists like Marcos and Rodrigo Duterte to lead the country they left behind while reaping the benefits of living in a liberal democracy. Wilfully blind to the flaws and abuses of their heroes, some would ask me, upon hearing that I was writing a novel for my creative writing PhD about the Marcos regime in the 70s and 80s, if I was correcting the “widespread lies” about Marcos Sr being a corrupt and murderous dictator. The same people would stake their hopes in Duterte to “cleanse our homeland of all the drug addicts and communists that hinder our progress”. In the comforts of a democratic, prosperous New Zealand where they would have been given due process if wrongly accused, they could conveniently forget how easy it would have been for them to be mistakenly labelled a drug addict or “communist” if they lived in Duterte’s Philippines.

About a week ago, a former student now living in Sydney sent me Facebook screenshots of Filipinos planning to hold a big celebration in Sydney for Marcos Jr’s win. One woman even celebrated the predicted collapse of the Philippine peso under another Marcos presidency, because this would mean the strengthening of the Australian dollar against the peso which would make it “easier to live like royalty in the Philippines now, if our Australian dollars can buy more pesos”. I can’t see how anyone else could celebrate the impending economic collapse of their homeland, if it weren’t for an insidious cynicism that has crept into their bodies and squeezed all the remaining traces of goodness and hope from their hearts. Such callousness ultimately leads to self-destruction, or in the case of many Filipinos overseas, an implosion they can witness comfortably from afar, preferably with a nice glass of Otago pinot noir.