After nine years in development hell, The Last Guardian has finally been released. Don Rowe enters a mysterious and melancholy world and finds the masterpiece of director Fumito Ueda’s career.

The first time I calmed Trico the bird-dragon with a gentle pat I felt certain he was going to die. Nothing in the plot would seemingly make it inevitable, but that a game in 2016 would encourage such a moment of intimacy and tenderness made me suspicious. My dog died barely three months ago, I’m not ready to hurt again.

The Last Guardian has been in development for nine years, existing in a sort of bureaucratic purgatory, drifting like an orphan between studios and backers. In that time games like Journey have introduced a similar melancholy minimalism, crowding what was in the early and crude days of video game development simply out of artistic reach.

But The Last Guardian has aged like a fine miso. A lost and empty world, populated with mythical beasts and an ancient God vibe. What is it about Japanese developers and creatives that they just nail that feeling over and again? Religion? A sense of the archaic nature of the living world? A reverence for form?

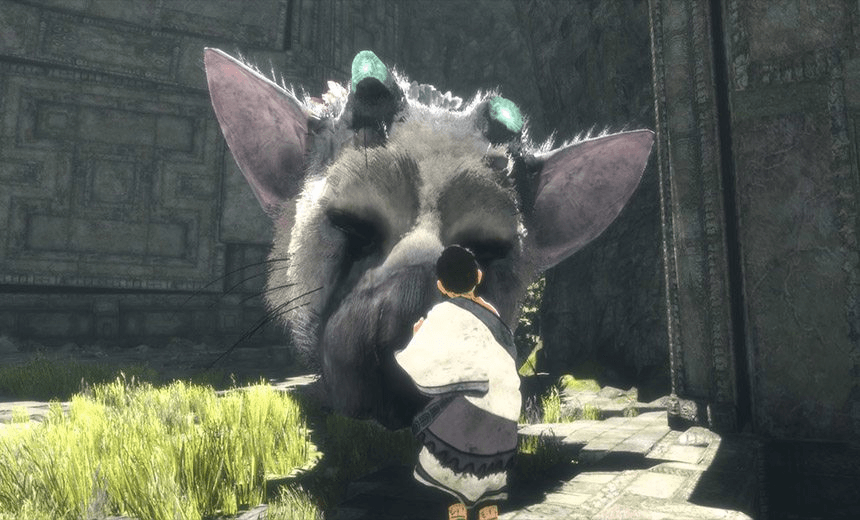

A robed boy wakes amnesiac on a paved floor far beneath the surface of the earth. His skin is covered in runic tattoos. Besides him is a feathered and mammalian dragon, chained, wounded and stuck with spears.

There are no maps, no health bars, no quest markers and no written objectives. The game isn’t broken or unfair, it just asks a little more in the way of patience and problem solving – truly an indictment of my attention span and temperament.

In this way, solving puzzles is generally a matter of logical assumption, taking into account Trico’s moods and desires. A 4-foot boy can’t push around a dragon, but he can manipulate his environment to encourage certain behaviours. For that purpose, barrels of luminous blue butterflies are scattered around the ruins and can be used as a lure to guide Trico. Mostly though I found myself finding buckets just because it felt like a nice thing to do. There’s no obligation to rub a dogs ears, or to feed a bird-dragon butterflies, but boy does it feel good.

In The Last Guardian director Fumito Ueda’s second game, Shadow of the Colossus, a young boy named Wander journeys through a forbidden land in order to save a girl. There are no towns, no dungeons, no characters with which to interact, and nothing to fight but 16 ancient colossi. Wander’s only companion in this vast and minimal wasteland is his horse, Argo, and it is the relationship between man and horse that has proven the games most emotive and enduring feature – despite the ultimate objective of saving Wander’s romantic love.

The Last Guardian is an extension of that same dynamic. But this time, it’s shared need that brings you together. From Trico’s back the player can jump to hidden areas, opening otherwise unaccessible routes for the pair to traverse. And unlike Shadow of the Colossus, the player in The Last Guardian is totally unarmed and reliant on Trico to crush his enemies to death. Then, after the act of killing turns Trico into a shell-shocked and catatonic mess, the player can sooth him with a reassuring pat behind his giant feline ears.

The animation is whimsical, exaggerated and perfect. The robed boy leans against unprompted against banisters and walls, pats Trico without player input and generally flops and bumbles like a child. Trico moves like what he is, some bizarre cat dragon bird thing, with dog whiskers and a puppy whine.

In an age of photorealism and grim-dark fantasy, The Last Guardian’s graphics are eastern to the core. Intentional oversaturation washes the world into an opium dream through which the player wanders miniscule amongst the towering ruins and rocky outcrops reaching into the sky. Occasional texture clipping and a clunky camera are weak points in what should by now be a polished release, however, and dark areas are occasionally too dark.

The soundtrack, composed by Takeshi Furukawa and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, is as iconic as anything from a Studio Ghibli release. Soaring crescendos fade to plonking keys only to rise again, crashing and booming, depending entirely on the situation. It would have been easy with such a prestigious and accomplished soundtrack to cram The Last Guardian with music, but often it’s the absence of sound that makes it notable, as Furukawa outlined in an interview with PlayStation:

‘The compositional process was more like sculpting, and trying to find the essence of the score. Carving away, taking away, it’s actually a subtractive process.’

I imagine Ueda faced a similar creative challenge. With games cramming in more, more, more, turning into dopamine-dispensing crack machines, it says something that to create such an emotive and touching experience is a matter of stripping back the clutter.

And as for Trico’s fate, Ueda says that’s ‘up for interpretation’.

This post, like all of our gaming content, is brought to you by the Last Guardians at Bigpipe.