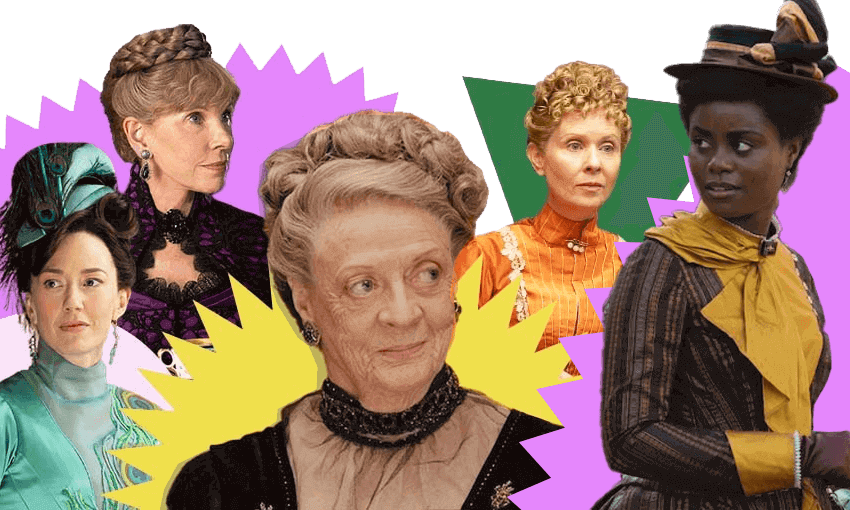

What if you took the best part of Downton Abbey and multiplied her? You get the best bits of The Gilded Age: the women.

When you think of Downton Abbey, what do you think of? Do you think of Mary killing a man via sex? Do you think of them killing off their romantic lead in an unceremonious car crash? Do you think about Mrs Hughes wandering around, muttering about murder? No. You think of Dame Maggie Smith as the Dowager Countess, stealing away scenes, episodes and entire seasons with a single raised eyebrow.

The role won Smith a slew of Emmys for doing the sort of acting work she could perform comatose, but those Emmys weren’t ill-awarded: she gave life, vigour and vinegar to a show that could often feel like BBC-sanctioned anti-anxiety meds. Not that many viewers were complaining, if the six seasons and two movies are anything to go by.

The Gilded Age, set in turn of the century America, is creator and writer Julian Fellowes’ follow-up to Downton Abbey, and sits largely in the same milieu. Like Downton, The Gilded Age is concerned with the haves and the have nots, with old money and new, and features lots of expensive looking sets and even more expensive looking gowns. It occasionally dips into high drama (Death! Loss of fortune!) but largely exists in the realm of low-stakes social drama (Ankles showing! Not being invited to a party!).

The most obvious change is that this show is set in New York, not Yorkshire, but Fellowes has also widened his lens beyond a single fabulously wealthy family and their servants. While The Gilded Age focuses on a range of families from varying backgrounds, the two that take centre stage are the Brooks (no relation, presumably) who represent old money, and the Russells, railway-owning tycoons who intend to muscle their way into New York society by hook or by crook.

Fellowes has also figured out that we don’t come to these shows to see men push papers and tighten ties. Nobody cares about Lord Grantham and his repressed emotions. We care about the Dowager Countess (Violet, if you’re nasty). As if in response to my specific, unvoiced, request, Fellowes has filled this show with variants on that one iconic character. It’s an embarrassment of riches.

The most obvious parallel to the Dowager Countess is Agnes van Rhijin, played by the reliably resplendent Christine Baranski, who can steal a scene with one hollow chuckle. She’s the closest thing the series has to a villain, but a more appropriate label might be anti-hero. We should hate her – she’s the representation of everything wrong with society, all about restrictions and the way that things should be done – but we can’t. Baranski adds a melancholy undercurrent to each withering glance and vicious bon mot, a constant reminder that her rigid social mores will break before they bend.

Less obvious but no less crucial is Ada Brook, Agnes’ sister and ward, played by Cynthia Nixon at her least Miranda Hobbes. Ada is a mirror image of Agnes: while she seems soft on the surface – as exemplified in one memorable sequence where she loses her dog Pumpkin – she’s always watching and always absorbing. Even though her niece describes her as “kind but not clever”, you get the sense that Ada won’t be brought down when rust comes for the gilded lot.

On the other hand, Carrie Coon’s Brenda Russell, very loosely based on real-life 18th century socialite Alva Vanderbilt, is essentially what you would get if the Dowager Countess dropped the “o”. By which I mean, she’s delightful to watch. It helps that Coon is doing an extremely specific accent that belongs to no region but instead drowns every sentence with disdain and dollar bills. Brenda is also the source of much of the series’ drama: she is excluded at every turn from higher society, purely because she came into her money rather than being born into it. Watching her plot and scheme out in the open, disrespecting people to their face, is glorious. She wears her wealth as proudly and unashamedly as she wears her gowns, adorned with flounces, ruffles and a runway’s worth of taffeta.

There are other women in the series, including Marian Brook (played by Louisa Jacobson, the third Streep daughter to go into acting) who is born into money, but still new to this particular society. Marian is the least interesting, by which I mean she has a moral compass and doesn’t get very many funny lines. Perhaps the most engaging of the non-Dowager-adjacent characters is Peggy Scott (Denee Benton), a Black woman from Pennsylvania with aspirations to make it as a writer in New York. Her presence provides a compelling tension in the series, forcing the characters to address race in a way that they, uh, didn’t really have the opportunity to in Downton Abbey, to put it nicely.

All in all, the formula for The Gilded Age’s success is simple. Take the best bits of your best character, multiply them into more characters, and place those characters in opposition to each other. Hire some of the best actors of the day to play them – seriously, Carrie Coon is doing the Lord’s work here – and boom! You’ve got yourself an entertaining TV show. Grantham who?

The Gilded Age starts streaming on Neon tomorrow; episodes drop weekly on Tuesdays.