Harry Wynn, director and writer of TVNZ’s Queer Aotearoa: We’ve Always Been Here, reflects on making the groundbreaking documentary series.

The first seed of the idea for Queer Aotearoa came to me during a regular dog walk. I found myself wondering: “when did it become legal for adult men to have consensual relationships in New Zealand?” To my surprise, it was only in 1986 – six years before I was born. Even more shocking, it was only a year after I was born that it became illegal to deny someone a job or rental property because of their sexuality or gender identity. I had always imagined New Zealand as a progressive little utopia at the bottom of the world but, for queer people, progress came surprisingly late compared to places like the UK.

This moment on the dog walk felt like opening Pandora’s box. As someone who benefits from the hard-won rights of activists who risked everything to challenge a repressive status quo, I was embarrassed by how little I knew about our own history. When I searched for documentaries on key events and change-makers in New Zealand’s LGBTQIA+ history, I found almost nothing – just a few old clips from Queer Nation. This glaring gap in access to our own history made me realise how essential it was to preserve these stories. With time running out, it felt urgent to capture the voices of those who had been part of these movements while we still could.

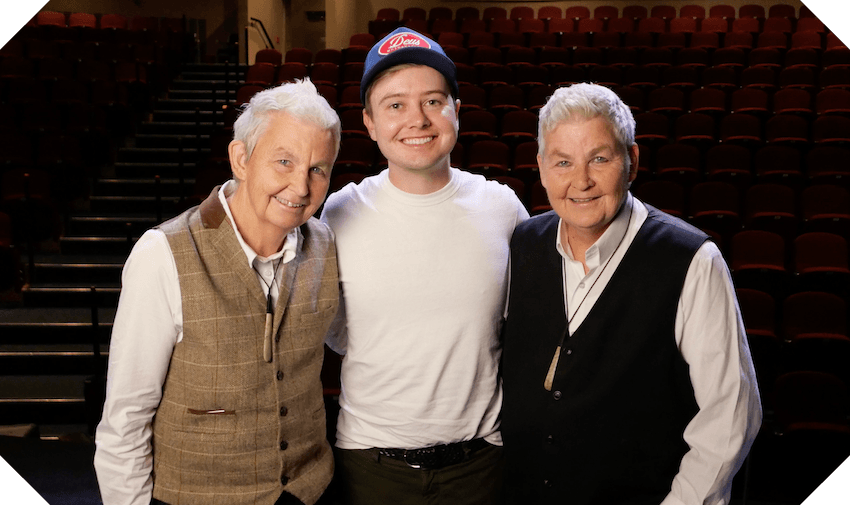

Working with producer Orlando Stewart was a no-brainer. He had made the TVNZ series When Bob Came, a documentary about the enduring cultural impact of Bob Marley’s one and only visit to Aotearoa in 1979. His experience with utilising TVNZ’s extensive archival database, which spans over a century, proved invaluable. This treasure trove helped us visually support the stories shared in interviews. Among the gems we uncovered were experimental documentaries by Geoff Steven about Auckland’s nightlife in the early 1980s, as well as old interviews with queer icons like the Topp Twins, Hudson & Halls, Carmen Rupe and Georgina Beyer.

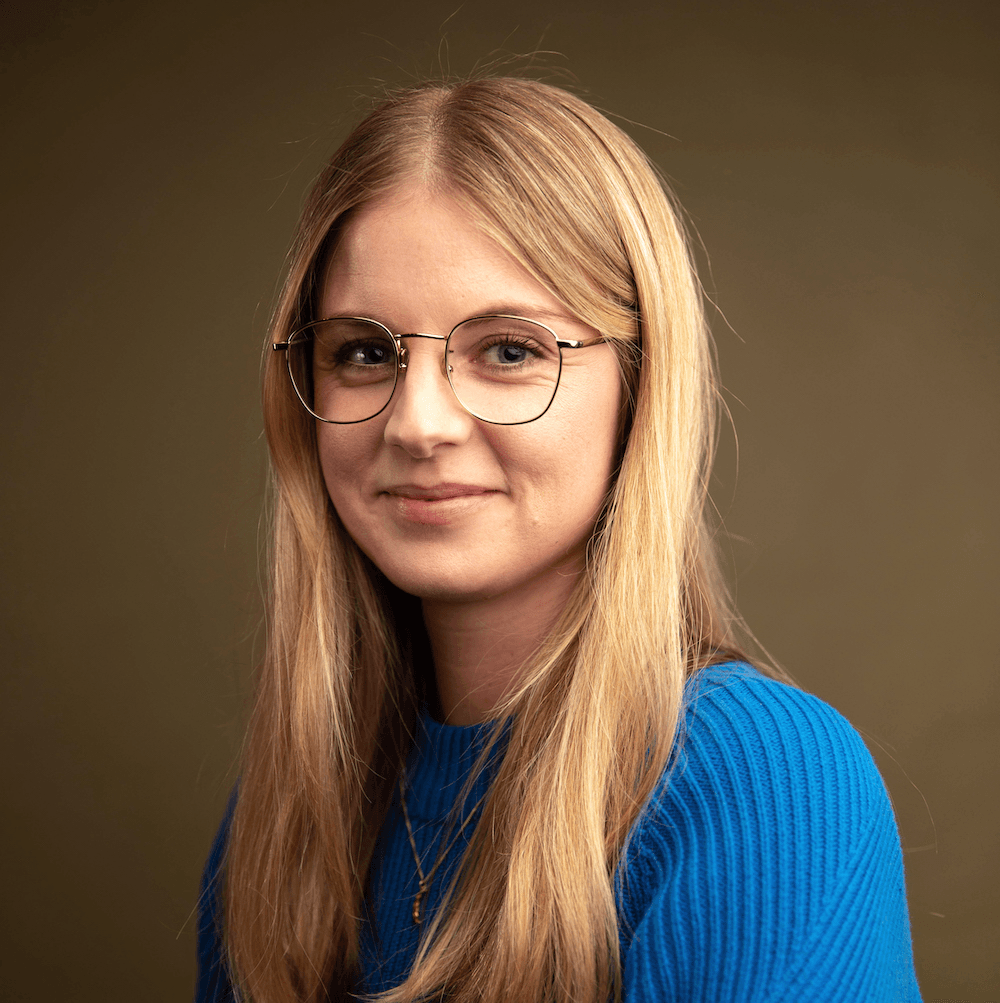

I think audiences will be surprised by how progressive some attitudes were in the past. Georgina Beyer’s Wairarapa campaign, for instance, included interviews with several middle-aged rural male voters who said they couldn’t care less about a politician’s identity, that it was her character that mattered most. Then there are also the interviews where reporters reveal blatant intolerance toward LGBTQIA+ people. Condensing all of these stories into six half-hour episodes was no small feat (shoutout to our brilliant editor, Sacha Campbell.)

When we started this project, I saw it as history worth telling. But what I didn’t expect was how deeply it would move me. We sat down with 35 interviewees for the series, and many shared the most difficult experiences of their lives. Mike Puru spoke about his fear of being publicly outed – a fear that became a reality for other entertainers. Joan Bellingham, a lesbian nurse, was sent to a psychiatric ward halfway through her training and committed for 12 years, enduring countless rounds of electroconvulsive therapy to “fix” her. Michelle Lewin, a trans woman, had to leave her dream job in the Air Force because it became unbearable to live as someone she wasn’t.

In 2025, events from 1986 or 1993 can feel distant or even irrelevant. But as recent events here and across the world have shown us, knowledge is power, especially for minorities whose rights can be stripped away with the stroke of a pen. Learning what LGBTQIA+ people have endured in New Zealand underscores how far we’ve come and how fragile progress can be. History shows that it doesn’t take much for the silent majority to shift their views on what rights they think minorities “deserve”. That’s why understanding what’s at stake is so important, while still finding the warmth and fun through our wonderful host, Eli Matthewson.

I know that for some in the LGBTQIA+ community, things like pride parades, rainbow flags, and overtly camp imagery can feel off-putting. Our rights are built upon activism and protest movements, and Pride represents activism on our community’s own terms. We gave a lot of thought to how we could make the show broad enough to resonate with people who are still working through their identities, as well as straight cis-gendered people. I hope this show and its exploration of our queer heritage in Aotearoa can serve as a gateway for people, no matter where they are on their journey.

For me, this is the show I wish I had when I was 21. My hope is that it passes down our queer history to younger generations, reaffirming that we’ve always been here – and ensuring that our stories will be here for those who come after us.

Queer Aotearoa: We’ve Always Been Here comes to TVNZ+ on Feb 1.