The stage is set for New Zealand to allow more research into infertility and better IVF treatments. After more than a decade and a half, the committee in charge of giving advice on embryo research will be updating their guidelines. But is New Zealand ready?

Currently, there’s effectively a blanket ban on viable embryo research in New Zealand. That is, on research where the embryo (in humans, a developing human less than nine weeks of age) could develop into a baby.

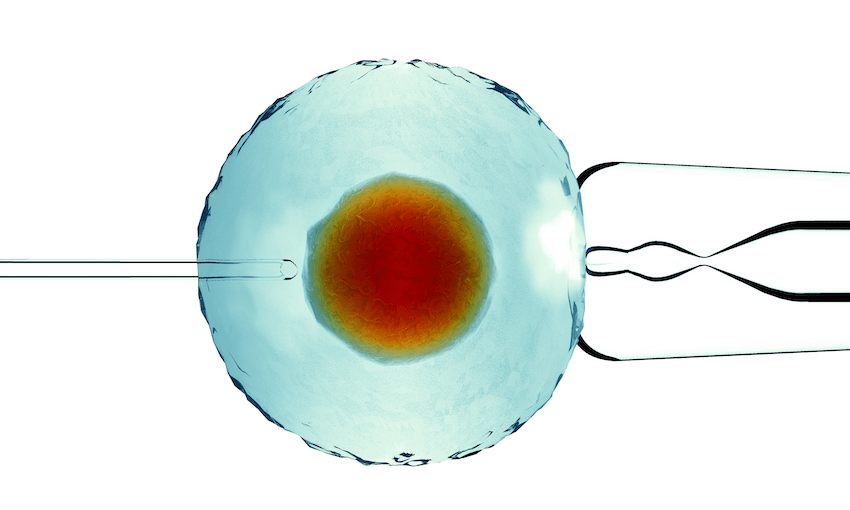

Clinicians and fertility experts have said the ban has stalled necessary research that could improve the success of reproductive technology like in-virto fertilisation (IVF), which currently has between a 10 and 50% success rate.

Research on embryos isn’t technically banned under the act that outlines the rules around it, but does require approval from the ministerial ethics committee. That ethics committee works off a set of guidelines from a panel of experts called ACART (the Advisory Committee on Assisted Reproductive Technology).

But those guidelines are outdated, say those who were instrumental in putting them together, and were last revised in 2005. It’s up to the minister of health to tell the committee to revise the guidelines.

In March that panel of experts was given the green light by the minister to review the guidelines.

“The way the guidelines are set up at the moment with its reference to research using non-viable [embryos] means that they can do no research on that basis,” minister Andrew Little told The Spinoff.

“If we want that research to happen and want to have the medical and health benefits to go with it, then we need to change the guidelines.”

“It sounds like a little bit of a breakthrough,” said Cindy Farquhar, a professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the University of Auckland.

One of the studies she proposed, comparing how long to grow IVF embryos in a lab before transfering them into future mothers, was previously rejected by the committee even though the methods mimic those IVF clinics use. Fertility clinics routinely transfer embryos at different times. When that’s done it’s left to the decision of the clinic and doesn’t require ethics oversight.

ACART chair Kathleen Logan told The Spinoff that the committee will consult the public on what researchers can do with embryos, eggs and sperm.

“The research guidelines, ideally, will provide a robust ethical framework for research to ensure we can get the benefits of assisted reproductive technologies, while taking into account consultation feedback from the public, to make the guidelines the best they can be and appropriate for Aotearoa New Zealand,” she said.

Research suggests that although some New Zealanders hold strong views that embryos should be protected and not exploited, religious viewpoints seem to go both ways, both for and against the work.

Logan has started putting feelers out to researchers about what they’d like to study and says most relate to improving the quality of fertility services. This could be things like comparing different liquids or gels that embryos grow in, finding better ways to store embryos or when to transfer embryos for IVF (similar to Farquhar’s study).

It’s unclear at this stage what the committee will focus on or how the guidelines will change.

The go-ahead in New Zealand comes just as international rules around embryo and stem cell research also get a refresh. The international guidelines, produced by the International Society for Stem Cell Research or ISSCR, were last updated five years ago.

The push for both revisions comes from the rapidly-evolving science on the topics. Scientists have found ways to inject human stem cells into an embryo from another species, in the hopes of one day getting a pig to grow a human heart, for example, or can use techniques such as CRISPR, which acts like scissors to cut bits of DNA, to edit human genes.

These advances could help treat and prevent inherited diseases, improve fertility treatments or develop ways to regrow injured or missing human body parts. But they also raise complicated ethical, religious and beliefs questions, says Robin Lovell-Badge, Chair of the ISSCR Guidelines Task Force.

“Some find these scientific advances scary and uncomfortable,” he wrote in a commentary in the journal Nature. “Most scientists want clear boundaries delineating which experiments are acceptable, both legally and to society. And the public wants reassurance.”

One of the biggest changes to the international guidelines is relaxing the 14-day rule, which states that research embryos are only allowed to develop up until this point before being destroyed.

The guidelines now say that, if there’s broad public support for it in a country and local laws allow it, ethics committees could allow research that goes beyond the 14-day threshold. Essentially, more developed embryos could be used in research.

The information from those more-developed embryos could prevent suffering for people who are infertile, have miscarriages or have an inherited disorder, according to Lovell-Badge.

The ISSCR did not set a new limit on how far embryos could grow, saying the original limit was arbitrary anyway. “It was a compromise that was accepted to allow some experiments to go ahead against the opposition who didn’t want any at all. It’s far more important that the reason for doing the experiment is looked at really closely,” said Lovell-Badge in a press briefing.

The New Zealand committee will take these international guidelines into consideration, says Logan, alongside other international ethical positions, but “in a way that supports the unique values and situation of Aotearoa”.

Previously:

NZ scientists set to lose out on major embryo research breakthrough