Climate change is the defining challenge of our times. The Spinoff is devoting a week of coverage to the issue, its advocates, complexities, and solutions. Today, five journalists discuss the intricacies and importance of covering climate change.

Climate change is the biggest story on any editor’s newslist right now. Legendary environmentalist David Suzuki wants journalists to drop covering things like the Dow Jones, and focus all their attention on climate change.

But it’s one of the hardest stories to tell. It’s a scientific slow burn, wrapped in politics and vested interests, surrounded by visions of a firey apocalypse. It’s full of numbers and data and uncertainty. Journalism has never had a more important or difficult task.

The Spinoff caught up with five Kiwi journalists dedicated to climate change, about the challenges and rewards of covering this massive story. They discussed why it’s such an important moment for climate coverage, how to tell the story, and what they hope their journalism will achieve.

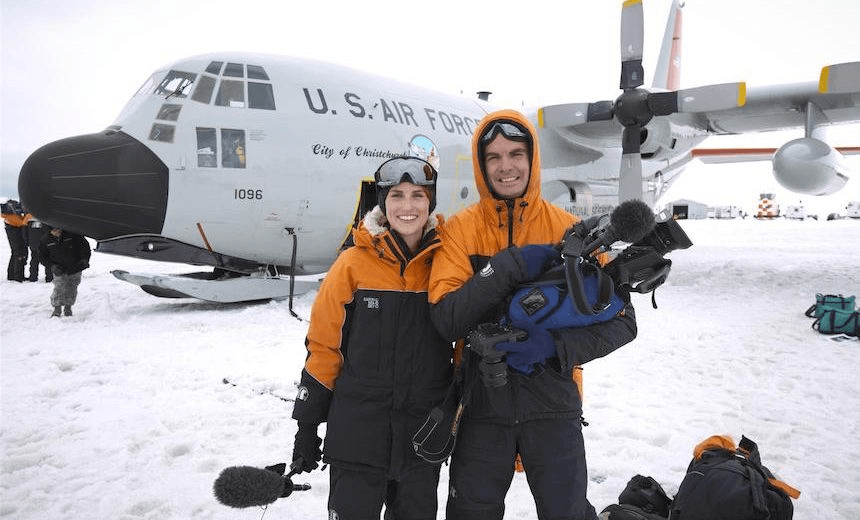

Samantha Hayes of Newshub grew up in New Zealand’s great outdoors on foot, horseback, or in a helicopter, and her journalistic gaze naturally fell on the environment, and on climate change as one of its great threats. On the global warming beat, Sam has beamed into New Zealand’s living rooms from Antarctica, the Pacific and the Copenhagen Summit.

Charlie Mitchell is a new generation of environmental journalists, and covers climate change (among many other things) for the Press and stuff.co.nz. He’s covered the effects of sea level rise on the West Coast, and recently returned from Kiribati where he witnessed the social consequences of climate change that are happening right now to Pacific communities.

Kennedy Warne co-founded New Zealand Geographic magazine in 1988, and served as its editor until 2004. He has published stories on climate change in perhaps the most famous magazine of all – National Geographic.

Jamie Morton is the New Zealand Herald‘s science reporter and was in Paris in 2015 to cover the historic global commitment to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions and hopefully save the world…

Veronika Meduna was as a microbiologist before she became an award-winning science journalist. She previously produced and hosted a RNZ’s weekly science programme and is now the New Zealand editor of The Conversation.

And in an environmental journalism rite of passage, each one of them appears to have visited either Kiribati or Antarctica in pursuit of the climate change story.

Here they share their thoughts on:

Why climate change is such a hard story to tell

Samantha Hayes: Any story that is based on numbers, statistics and graphs is going to be difficult to get your head around and challenging to hook people into. Add to that the fact that the villain is invisible and you’ve got a tough task on your hands. Pile on top of that the scale and time frames being talked about – it’s a global problem that will occur over centuries – and there is no denying it’s a tough sell. So what you need is great talent – science communicators who are charismatic, and can break it down to a simple and punchy message – and good local examples of how this massive, overarching threat will impact your country, city or town or street.

Charlie Mitchell: I think one of the major issues journalists have with covering climate change is that it’s so abstract. The timeframes are always massive, for a start: You can write about how New Brighton [in Christchurch] will be underwater a century from now and it won’t resonate, I guess because it doesn’t feel real. It also deals a lot in scientific uncertainty, which some people are suspicious of, perhaps not understanding what that means.

Veronika Meduna: Even though climate change is one of the biggest issues that will affect all aspects of our lives, it is a slow-burning emergency. It’s a long-term issue, it’s complicated, it’s threatening, there are a lot of vested interests, and it’s calling for a significant change in behaviour. None of this makes it an easy story to tell.

Climate change stories are up against human psychology, which makes us resist change and care less about less imminent dangers. They are also up against intentional smokescreens and cherry-picking of data, intense lobbying and straight denial.

Kennedy Warne: Part of the difficulty is that early reporting of climate change tended to emphasise that its most severe effects will be decades and centuries away. This has tended to lull the public – which has a perverse aversion to facing its responsibility to future generations – into a false sense of security, the assumption that the danger is distant in place and time. In telling climate stories today, media have to break through that fog of complacency. A further challenge is that climate change is the classic slow-onset threat. Humans are hardwired to pay attention to sudden disasters, not gradual ones.

Jamie Morton: It’s the biggest threat and challenge facing the planet and it can appear too big for some people, which means we have this apathy risk. Some recent studies have also shown that focusing too much on the doom and gloom – and that includes the apocalyptic messaging you hear from many big-note travelling advocates – can also turn people off.

How to tell climate change stories well

SH: Climate change stories have a tendency to be negative and I think people have a low tolerance for depressing statistics and doom and gloom so you need to put it in context, and I try and add an expert’s opinion that provides a solution or advice on mitigation.

JM: Kiwis care about climate change – we’ve seen that reflected in survey data – but that doesn’t mean we can write anything about the issue and expect that everyone will read it. You have to ask yourself those questions every other journalist does. How will this be relevant or interesting to my readers and why is it important? What are you telling them that they don’t already know? I’ve also found readers will spend a lot of time reading a long piece on climate change if you’ve told and presented it well – and this doesn’t just apply to local stories.

Therefore we need to be careful not to misrepresent the science or take any silly leaps in language, particularly when we’re writing about models or ranges of probability. I recall one headline error that basically told people the world was imminently bound for Biblical levels of sea level rise, which embarrassed the scientist concerned in front of colleagues at an overseas conference. Fortunately, that scientist was Professor Tim Naish, who’s a top guy and was quite forgiving. My advice to journalists would be to work closely with scientists or study authors to ensure you’ll get it right.

VM: Radio, particularly in longform and outside studios, is great for getting the real thing – not just a person’s words but also a good impression of their overall personality. Radio is intimate, immediate and authentic. It can be great for climate change stories because voice carries emotion and connects listeners on a level far beyond words. Radio has a way of taking listeners to a place as well as engaging their imagination at the same time.

The narrative of the looming apocalypse

KW: There are reasons that climate change reporting has been sensational, alarmist and apocalyptic. The first is that sensation sells. Polar bears on shrinking ice floes, waves washing through Pacific island homes – these are dramatic situations, and obviously the media will tend to maximise the drama, often at the expense of perspective and context. But the second point is that climate change really is a looming catastrophe. Species extinctions, obliteration of ecological systems, human suffering and displacement on a massive scale – we truly should be alarmed.

However, there is at least a decade of research in the social sciences that shows that alarmism is counterproductive in communicating an issue like climate change. “Fear-based messages are more likely to induce apathy or paralysis through powerlessness or disbelief than motivation and engagement, particularly if not accompanied by an action strategy to reduce the perceived risk,” notes one researcher. Catastrophism presents the climate problem as overwhelming, “effectively counselling despair,” says another. A further line of research suggests that apocalyptic language, rather than encouraging action, actually promotes disengagement and motivational paralysis. In no scenario does catastrophist coverage of climate change lead to positive outcomes such as a personal and political engagement with the issues and commitment to decarbonisation.

CM: I’m a bit of a cynic, so I think climate change is inherently apocalyptic. I mean, as you drag the timeline out, it’s only going to get more and more ruinous for an increasingly large number of people. If you’re a journalist who takes the job seriously you should be reckoning with that in some way. Of course, you’ll get dismissed as fear-mongering by some people – I’ve had my fair share of that – but that’s no excuse not to write about this stuff.

VM: If the evidence is there for a bad outcome, I think it’s important to say so. But it’s equally important not to let an apocalyptic scenario just hang there without providing a way out of it.

Reporting from the Pacific Islands – the coal face of climate change

CM: What struck me is that while sea-level rise is almost an existential threat to [Kiribati], there are way more pressing issues right now, some of them climate related. They’ve been in a severe drought, and have barely any water to drink. The infant mortality rate is similar to that of the poorer countries in Africa. Children don’t go to school because there are no toilets. In terms of New Zealand, one of the major climate change issues worldwide is forced migration, and that may become a reality for Kiribati in the coming decades. Over 110,000 people live there, and we’re their closest wealthy neighbour. Where else are they going to go?

Reporting from the Copenhagen conference

SH: I went to Copenhagen and watched as every prime minister and president stood up and said climate change is real, it’s is a threat to humanity and we must act now. That was in 2009. All the summits since have had similar goals to Copenhagen but we’re still yet to see a legally binding agreement that would reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Is it depressing? I’m an eternal optimist so no it’s not depressing but it is frustrating. I have however seen attitudes change and support blossom for solutions to the problem. I think there is enough understanding and momentum now globally to see climate change addressed in a meaningful way.

On New Zealand media’s coverage of climate change

JM: A while back, RNZ’s Mediawatch show aired a segment which quoted a visiting overseas academic and painted a fairly sorry picture of climate change coverage in New Zealand.

That annoyed me as it ignored the fact that so much solid work is being done out there every day. Even moderately-important climate stories – usually new studies – typically get picked up by all the main media outlets. And then we’ve got a good number of journalists who specialise in climate change issues: Brian Fallow, Rebecca Macfie at the Listener, Adelia Hallett at Carbon News and others at New Zealand Geographic. So, yeah, for a country of 4.7 million, which isn’t much more than that of Sydney, we do okay. But people find it easy to trash the media.

VM: There are positive signs and new resourcing going into more specialised journalists’ positions, but overall the mainstream media story has been one of staff cuts. Science and environment journalism remains under-resourced and undervalued in New Zealand and elsewhere. I think science and environment coverage, and climate change in particular, should be equal to other major rounds in a newsroom, such as politics, business and sports.

Balance, climate sceptics and fake news

KW: There was a giant speed bump in media coverage when oil-company funding of climate change scepticism and outright denial kicked in. Denialist groups successfully turned climate into controversy, which had two effects. It took media attention away from the reality of the threat to the vacuous details of the pro/anti debate – more heat than light – and it scared large numbers of the public away from engaging with what the Parliamentary Commissioner of the Environment rightly describes as “the ultimate intergenerational issue.”

VM: We’ve known for a long time that climate change is happening and that we’re doing it, but for many years the media coverage stuck to asymmetrical debates, where one dissenting voice carried the same weight as hundreds of others. That’s changed dramatically in the last decade or so, partly because the evidence is no longer just written down in scientific publications but happening in front of our eyes.

JM: While we don’t see climate sceptics (deniers if you call them that) given as much oxygen in the media as was once the case, social media has enabled a troubling environment where bad science and fake news gets shared around and user algorithms can project ill-informed views back at people without challenging them. It bothers me how Facebook, which traditional journalism is competing with, uses the term “newsfeed” as though that’s what we’re actually getting.

The role of a journalist in the response to climate change

SH: My goal is to help people understand what climate change is, how it will impact them now and in the future and to give them some ideas about how they can help. I don’t think it’s acceptable for people to say they don’t understand it, or they haven’t done enough research to know what it is or what it means. This is too important an issue to bury your head in the sand (or rising sea). Scientists are pulling their hair out, they cannot understand why people aren’t listening to them, why governments aren’t acting. Our job as journalists is to create readable, watchable content that conveys the facts and their frustration.

VM: I wish it were that easy to change people’s behaviour. As a journalist, my goals are more subtle. It’s about connecting audiences with the information and stories that help them think through an issue and to decide whether they want to/need to do something about it. Credibility and evidence are important aspects of how I think about journalism.

CM: I think what people do with the information is really up to them. I don’t see behaviour-change as a useful end-goal for journalism. Systemic change, definitely: if it pressures authorities into being more proactive about the threat of climate change, that would be worthwhile. But when I’m writing a story I’m not quietly hoping the reader will think twice before buying a bottle of milk or whatever.

KW: I think anyone who cares about life on Earth – or who has grandchildren, and I tick both of those boxes – must have an interest in persuading fellow members of the species to act with the planet’s future in mind. In a TEDx talk in 2012, Grist magazine climate writer David Roberts pithily described climate politics as stuck between the impossible and the unthinkable. “Your job,” he told his audience, “anyone who hears this, for the rest of your life, your job is to make the impossible possible.” That sounds like a pretty good job description to me.

JM: As a science journalist, your aim is more just about putting the facts in front of people, and doing that job as well as you can. Whether this has any effect on action, you only hope.

Climate Change Week at The Spinoff is brought to you by An Inconvenient Sequel – in cinemas August 24.

A decade after Al Gore’s film, An Inconvenient Truth, brought climate change into the heart of popular culture comes An Inconvenient Sequel – highlighting the perils of unmitigated climate change and the need for more action. See it in cinemas from Thursday August 24.