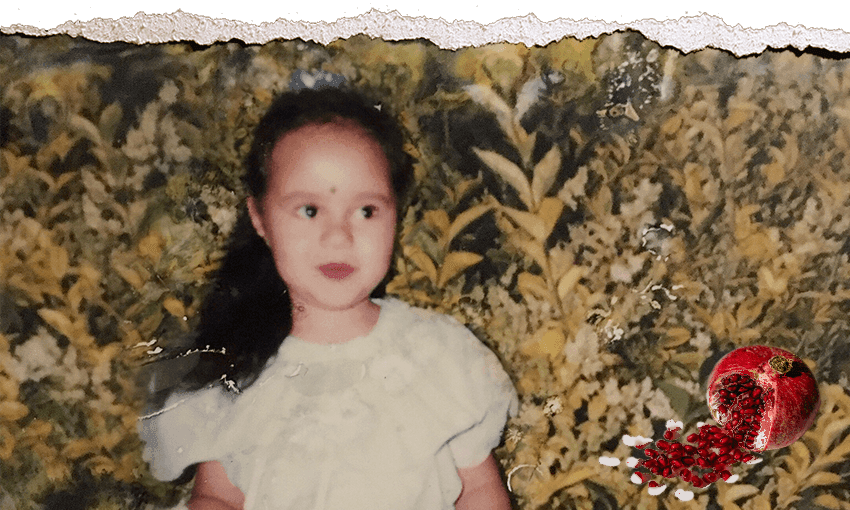

Before it became a hostile place, the Iran of my father’s youth seemed a sensual heaven of family and so much feasting.

When I was seven years old I watched Conan the Barbarian and asked my Baba joon (dear Dad), “What is a pomegranate?” He smiled as if remembering an old friend. He closed his eyes for a moment, the way you do when you travel vast spaces and immerse yourself somewhere other than where you are. He looked back at me, the lingering comfort of a happy memory on his face, and said very quietly, as if divulging a great secret, “Anar is the fruit of heaven. I will show you.”

Baba joon’s anecdotes of Iran filled my dreams with decadence and longing. His stories told tales of relentless desert heat. Summers that could only be survived with potions made from honeydew melon, mint, saffron or watermelon. Cities turned to snow, surrounded by mountains cloaked with white in winter.

The Iran of my dreams, the Iran my Baba joon illustrated for me, was a kind of heaven. The Iran I saw in family photos was one where people would sing and dance together with fervor in the street at any hour of the day or night. Where children would jump over bonfires into the early hours of the morning. Where women sat on the beach with their friends, the sun glistening on their bare shoulders, long hair draped down their backs or flowing behind them as they ran against the wind.

“It is a country that is alive,” Baba joon would say. “The people there, they are alive.” I wanted to know children who had names like mine. Names not found on pencil cases or mugs. I wanted to know children whose hair joined in a beautiful embrace between their brows like mine. Eyebrows that were being preserved for a ceremony of threading.

But we never went back.

When I was eight years old, in the early ‘90s, Baba found a pomegranate at a fruit store in New Lynn, West Auckland, for $7. He said, “This is a very precious fruit.” We placed it in the middle of the fruit bowl that sat at the centre of our table.

Our fruit bowl was always abundant and overflowing with Persian cucumbers, seasonal fruits and grapes, much to the amusement of my friends.

Kids I grew up with lived on Marmite sandwiches, fairy bread, saveloy sausages and tomato sauce. Grated carrots and sliced boiled eggs with grey yolks adorned their salads. Meals at their homes were strictly by invite only, their meals were portioned, and there seemed to be little talking at their tables.

They said my family was strange. We snacked on salted sunflower seeds, pistachios, and brittle flavoured with cardamom. Bergamot, rose and clove tea was offered to anyone who came through our door. The cooking of fragrant rice was a two-day-long exercise. Meals were served as a banquet. We talked, laughed and sang at our dinner tables. No one left our home with a hungry belly.

When my extended Persian family first settled in West Auckland after an arduous journey as refugees, my Māori side of the family took great pleasure in introducing them to local culinary delights.

Uncles dug the hāngi pit, Mum made boil-up, and the piece de resistance, a pig on a spit, was in full rotation. A culinary expression not available in Iran. It brought great amusement to my newly settled relatives.

As I grew older my Amehs (Aunties) taught me how to grow herbs, pick and dry them, and create stews with lamb and whole dried limes. They taught me how to grind walnuts into a paste, to be served with pomegranate syrup in a sour and sweet chicken khoresht (stew). In the formative years of my life, I came to know my Persian identity through my Baba joon, and through family who came to join us.

My childhood was imbued with the most brilliant amalgamation of tastes, scents and languages.

Mum made it her mission to ensure no man, woman or child who came from Iran to Aotearoa to join our family was left behind when it came to fitting into the wider culture. At this time mullets were the hairstyle of the season. No one was safe. Amehs, Amus (Uncles) and cousins all had their hair fashioned into the style that purported to state “business in the front; party in the back”.

My Baba sported a trucker’s cap, and called people “mate”, “cuzzie” and “bro”, vernacular picked up through his Māori in-laws. His accented vowels created new sounds out of old words. The curl of his “r” enveloping the vowels and alerting listeners to a tongue of foreign verses.

His attempts to assimilate were no match for the over zealous police officers who would pull him over when he drove with the tenacity and vigour he had learnt on the roads of Iran.

“I don’t know where you’re from but we don’t drive like that here. You want to drive like that, you go back to where you came from,” a young officer said to our Baba joon in front of me and my brother after pulling us over in Glen Eden. “I’m a New Zealander,” Baba said. “You don’t sound like one,” said the officer.

When we relayed the story to Mum she glared as she listened intently.

“He said go back to where you came from?” she hissed, picking up the phone attached to the wall, the way they were back then, yanking the coiled cord which had twisted into a ball. Mum would never accept anyone telling us that we didn’t belong.

Indeed, where else could Baba belong? When his homeland could not home him?

An officer came to our house in the days following Mum’s complaint. But nothing ever came of it, as the young officer had claimed we were lying.

It was just before Christmas, the time of Shab-e Yalda, the winter solstice, on the other side of the world. An occasion that predates Islam, Christianity and Judaism. The day had come to unveil the fruit of heaven. We gathered around the table, Barodaram (my brother), my Baba joon and me.

We watched our father slice the pomegranate gently into quarters with his pocket knife. There is an art to unveiling the contents of an anar. It is undertaken with precision, old knowledge and care. Tracing the groves with your fingertips. Only cutting into the white. Using water to separate the pillowy flesh from the juice rich magenta jewels.

It unfolded effortlessly; a blossoming rose. My brother and I gasped. I will never forget the profound and lush, deep, purple red. The fruit of my father’s youth.

My Baba was raised in a warm place. Where he was named after one of the Shanameh’s great kings. Where the fruit of heaven grew in abundance. Where anar decorated dishes at mehmoonis (family gatherings).

Where anar filled bowls on the table on the night of the winter solstice, and where children would drink its deep blood, fresh pressed juice, their inheritance from the earth.

I have hope that one day the world will know the Iran that was lost. The Iran that our parents remember before members of our Baha’i faith were actively persecuted. The Iran that drives the youth to demonstrate in defiance of decades of subjugation, removing with fierce determination the veils of oppression. The Iran that we have preserved in our hearts and our dreams.

The Iran that was, back before the land of my Baba’s forefathers – for thousands and thousands of years – rejected him. Rejected its own people. Suppressed their expression. Spilled their blood, spilling them out into far corners of the earth.

To New Lynn, where we would search for the fruit of heaven, and occasionally find it in fruit shops, for $7 a piece.