While the March 15 terrorist was not on the intelligence agencies’ radar, Haamid Ben Fayed has been. He hopes the inquiry will be a chance to address the systemic discrimination faced by Muslims in this country – but, as he tells Jo Malcolm, he doesn’t hold out much hope for change.

Haamid Ben Fayed thinks deeply before he speaks. He’s considered things very carefully before deciding to speak publicly. He relied on his Muslim faith to guide him but he is also acutely aware of what happens when you are Muslim and stick your head up. He didn’t want a photo of himself used.

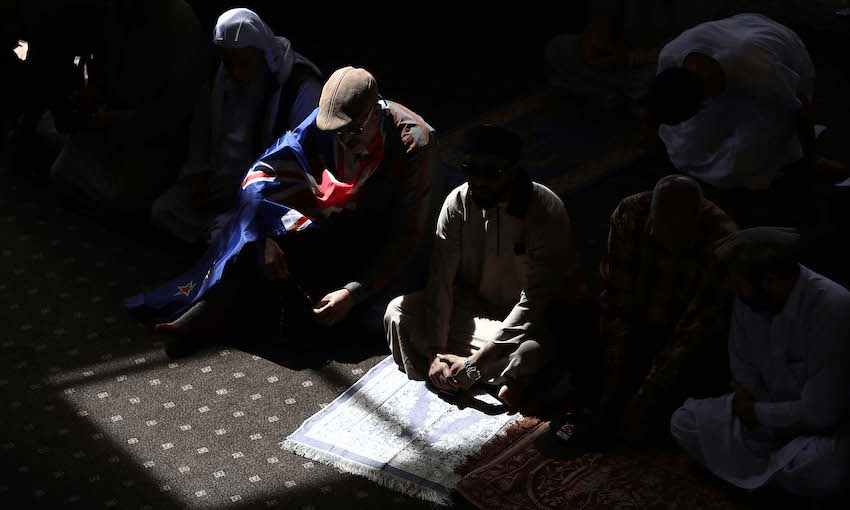

It’s been 21 months since the worst massacre in modern New Zealand history. Twenty-one months when so much has changed. The gunman was sentenced to an unprecedented life without parole, in August this year. The victims and their families, the sons and daughters, husbands and wives, mothers and fathers of those who were killed with a cold-blooded cruelty no one could ever imagine, eye-balled the offender in the dock, one by one, metres away from him, reading their victim impact statements. They cried, they forgave and some got angry. For those of us who witnessed this, it felt like some kind of closure. For the Muslim community, it’s not.

I met Haamid before the sentencing of the gunman in the High Court in Christchurch. I was there as an independent contractor who had been asked to provide operational support to the court’s media team during the sentencing. I am a former journalist and teach broadcast journalism at the University of Canterbury.

Haamid was part of a multidisciplinary team supporting the justice sector with the March 15th court processes.

I sat and listened to the victim impact statements as did Haamid. He said it was heartbreaking to hear the details of how their lives were ripped apart, but was so proud of the dignity and strength with which they represented themselves, their loved ones and their faith.

“Their bravery and their words will stay with me for the rest of my life.”

The government has just received the Royal Commission’s report into that terrible dark day in our nation’s history. It will be released, with some parts suppressed, next Tuesday.

I ask Haamid why, despite the outpouring of political and community support for those affected by the massacre, he’s not convinced much has changed. “New Zealanders are amazing people and in the aftermath of March 15, a sense of belonging was enhanced. But for many Muslims, myself included, ‘You are us’ feels more like an aspirational statement than a reflection of our reality.”

In Haamid’s view, that “reality” for many Muslims continues to be shaped by systematic discrimination and suspicion and a refusal by government agencies to engage with Muslims as a legitimate faith community in New Zealand, rather than a collection of ethnic minorities.

Haamid says there has been meaningful progress on the gun laws, the Christchurch Call, the handling of the court processes and a growing awareness of racism in New Zealand.

“But it’s my sense that the government has deferred all accountability until the release of the Royal Commission’s report. I really hope that it’s going to be an opportunity for the government to address actions in the past, the systemic discrimination that makes Muslims in New Zealand so vulnerable.”

Haamid’s own personal experience with New Zealand’s security services as a young man has informed his view that Muslims have too often been treated as objects of suspicion and targets for surveillance because of their faith.

“In the days following March 15th, the director of the NZ SIS, Rebecca Kitteridge, told the then justice minister Andrew Little that they were unable to detect Tarrant because New Zealand isn’t ‘a surveillance state’. She said, ‘We need a lead,’ despite all the places the gunman had visited, and the weapons and ammunition he had accumulated. My experience has taught me that Muslims are routinely targeted by the agency simply because they are Muslim – to be Muslim is a lead.”

In his view, such deep-set prejudice goes a long way to explain why the voices within the Muslim community who were raising alarm bells about Islamophobia went unheard and unanswered.

Haamid was born in New Zealand. His dad is originally from Libya, his mum from Mauritius. He went to Mount Roskill School in Auckland and says going to school was like having two identities.

“Going to school you try and fit in but it’s like living two lives. I didn’t really have a natural space in the Muslim community and I didn’t really fit in at school, so I was at a kind of crossroad. I wanted to learn more about my faith but there weren’t any pathways in New Zealand then. There was going to a mosque but many of the social needs weren’t met for young Muslims.”

I asked Haamid about the 9/11 attacks in New York and whether he suffered any backlash at school.

“I was 11 at the time and I remember Mum woke us up early for school and she was in a panic and told us what had happened. She was preparing us to go to school and be safe as we were easily identifiable as Muslims. It became the norm to get comments about terrorism, people calling you Osama and becoming thrust as children into the world of politics and having to defend our innocence. I had a choice then, I could abandon my faith or find the strength to own it myself.”

Haamid decided he wanted to learn more about his faith and after attending a Koran school in Sydney when he was 14, followed by a year of learning Arabic in Egypt, he then spent four years studying at one of the most prestigious international Islamic institutions in the world, located in South Yemen. His parents had travelled there on holiday and decided to stay. For Haamid, New Zealand was always home.

He says he was a very different person coming back at 20 than the precocious 14-year-old who had left. “I had no questions about who I was any more. I was 100% confident in that. It’s the main grounding that I have, it’s my values framework, God is watching and I know what He expects of me. It’s about being able to live your life, understand what your path is and what your actions mean. You strive to do your best, if you fall short, and reflect sincerely, God forgives you.”

Haamid studied politics and then completed a law degree in Auckland. He had a strong sense of community and had many friends, organising events and activities.

Through the 1990s, Yemen was a hotspot of terrorist attacks and unstable government. Post 9/11, Al-Qaeda was frequently in the news, often in connection with Yemen. “The government spy agencies were watching people coming back from Yemen. I remember prime minister John Key saying they were watching New Zealanders living in Yemen,” he said.

Haamid describes the surveillance. “They would arrange to meet you at a location like a McCafe. It was quite strange because they were trying to get you to identify people from your community. They would show you pictures of people but they wanted to be discreet to prevent anyone seeing what they were showing you.

“Instead of photos, they would bring a JB Hifi catalogue and instead of having the screenshots from a movie, there would be someone from the community’s picture inserted instead. It’s funny in hindsight, but also highly problematic, but I was pretty naive as a 20-year-old and I just went along with it. They would also leave Isis recruitment catalogues with bomb-making instructions to see what you would do with them.

“The dangerous thing is the psyche they foster, they target the most vulnerable people in our community, change meeting locations at the last minute due to the area being compromised and isolate you, and they do not tell you your legal rights.

“I am OK, but it has had a really detrimental impact on some of the people targeted. Imagine someone with compromised mental health telling a crisis worker they are being spied on – it reinforces the perception of paranoia, allowing the person to be further marginalised and isolates them further. Some have attempted suicide.”

Haamid isn’t denying that the government was within its rights to look into those coming into the country from a place like Yemen, but what he is pointing out is the systematic targeting of Muslims solely due to their faith, with no evidence of any wrongdoing.

“Past governments have perpetuated a narrative that there is a threat in the Muslim community, yet the few cases of radicalisation that have come to light have been because of community reporting, not surveillance.

“People’s parents and friends are the real frontline. There is zero tolerance for radical behaviour within the community, in fact the one Muslim that is regularly reported in the New Zealand media was never part of the community, he slipped through the gaps because he wasn’t among us and that’s the only place they are looking.

“Rebecca Kitteridge apologised to the Muslim community for statements that were made about our community relating to so-called ‘jihadi brides’, young women leaving New Zealand to join Isis overseas. There was no evidence of this happening here.”

The Islamic Women’s Council of New Zealand also spoke up at the time, saying it resulted in Muslim women feeling unsafe, targeted and highly vulnerable. It also spoke of countless occasions of trying to talk to agencies and authorities about a rise in right-wing Islamophobia and racism in this country.

The council has already released its submission to the Royal Commission. “If [the council] had been taken seriously, the SIS would have kept an eye out for activity by white supremacists,” says Haamid. They managed to catch young Muslim men sharing Isis videos in New Zealand and have had them prosecuted. To discover this, they were spying on the young men online. Why was there no equivalent spying on young white supremacist men?”

The council said the police failed in not developing a national strategy to deal with threats against Muslims and mosques. Among the council’s recommendations, it wants an apology for the failings of the SIS and government agencies in relation to the attack.

Haamid says since 2014, when increased surveillance measures were brought in, powerful agencies worked together to target Muslims, with fringe agencies engaging with them as ethnic minorities to try and temper the fallout.

“Teaching the public service and the public to say ‘assalamualaikum’ [peace be with you] is not going to fix this one.

“This is what I mean about wanting a change. It’s uncomfortable for the government to accept that Muslims were targeted. A good proportion of Muslims were regularly interviewed by intelligence services and none of these people have ever been connected to threats or extremism. People doing good work in the community.

“It casts a shadow over your whole life. It’s rational to assume there would be some interest but there is no way to find out whether it was temporary, whether you have now been deemed safe and are no longer under surveillance.

“Your whole life you have to assume you are under watch. No one will tell you because of so-called ‘national security’ concerns whether it’s stopped. You live your life under a cloud.”

The Human Rights Foundation released research in late March last year that revealed how the SIS used “informal chats and offers of payment” to young Muslim men who felt pressure to spy on their mosques.

Then justice minister Andrew Little said an inquiry into the SIS and other agencies was vital to test whether security agencies had organisational blind spots to a white supremacist threat.

I pick up from Haamid there is real anger and a very sad sense of frustration regarding the failure of the intelligence services to pick up someone like the Christchurch terrorist. “They couldn’t pick him up even though he bought 7,000 rounds of ammunition, he had visited a whole lot of hotspots and lived in an online world of right-wing extremism and hate. He raised a whole lot of red flags but he wasn’t Muslim so he wasn’t on anyone’s radar.”

Haamid believes the Royal Commission may go into why the shooter wasn’t on anyone’s radar for suspicious activity and why he was able to obtain a gun licence here, but there are bigger questions to be asked.

“The government’s response to the Royal Commission can be an opportunity to move on. It’s been 21 months since the massacre and they’ve kicked the ball away, not accepting any responsibility or addressing the issues until after it’s released.

“We have been patient. The victims have woken up every day for almost two years with their injuries and without their loved ones, so really we hope that the next phase is one of honesty and meaningful engagement.

“I will tell you one thing – on March 15th, we were so relieved it wasn’t a Muslim who had done something so terrible. If it had been, we all would’ve been on trial as a community the next day, and that’s the big difference.”