Hera Lindsay Bird on her Bildungsroman.

I would never have gone to Germany if it wasn’t for the bee sting.

At primary school, I belonged to an evil quartet of girls. It feels imprecise to call them friends. They were more like coworkers, in the great open-plan office of primary school. I can’t remember what we talked about or had in common. But I do remember being unceremoniously dumped after I was stung by a bee on the field of Thames South School and made a scene in front of the boys. This humiliating display was the last straw for my friends, who delivered me a handwritten note terminating my contract.

I was stunned. Not so much by the rejection, but the surprise. I spent two lunchtimes in the library considering my options. The idea of continuing at school without friends was impractical, so I scoured the playground, picked out a likely candidate and set about winning her over through a tactical combination of prolonged eye contact and targeted smiling. Miraculously, this worked.

My new friend’s name was Ilana. She came from a German family, and we got on like a haus on fire. We listened to audiobooks about shipwrecks and prank-called the Nesquik consumer hotline. I married her dog, Ronja, in an elaborate backyard ceremony. I was enchanted, not just by my new friend, but by her extended family. She lived with her German mother and grandmother in a small cottage overrun by chickens. They drank gallons of Chi’ mineral water and bickered amiably, in that dour Teutonic way Germans have. We spent many long summer afternoons waging war against the white butterflies that ravaged her grandmother’s cabbages.

When I moved cities, we fell out of touch. But my fascination for the Germanic people remained. It was this friendship which prompted me to take German lessons, which weren’t an option at my high school. I signed up for a correspondence course and was allowed to borrow a dingy room in the school’s basement to wind and rewind my cassette tapes. Möchtest du ins Kino gehen? Ich habe, du hast, wir haben.

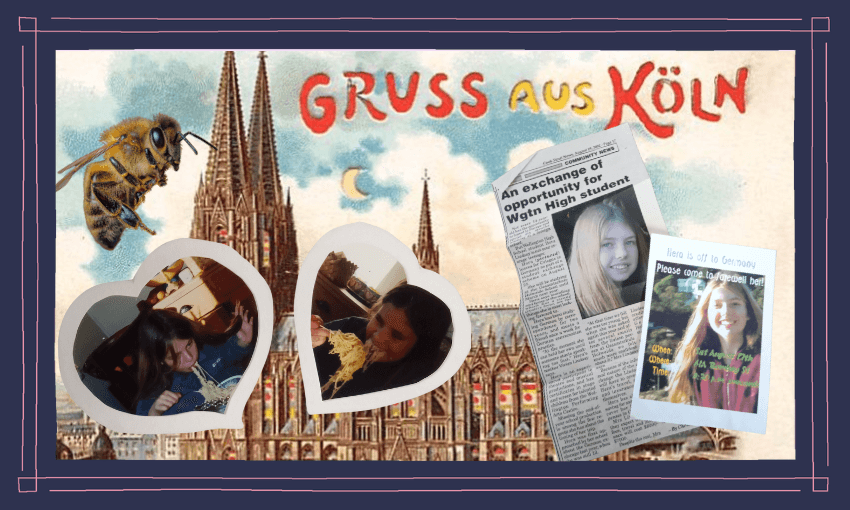

I can’t remember how the exchange came about, only that it was bizarrely informal. A German couple whose daughter wanted to study in New Zealand proposed a child swap. Although this initial arrangement fell through, the German school facilitating it found me a replacement family. My parents were dubious. Fourteen seemed too young. But I was adamant I could handle it. I was to arrive in Köln in August 2002 and stay for six months.

To save money, I got a job at the deli section of the Khandallah supermarket, serving precise 100-gram fistfuls of ham to rich pensioners. I was told I needed to learn to ride a bike, and my dad took me for long, wobbling practice rides along Red Rocks Beach. There was a farewell party where I was given a pounamu necklace, blessed by my extended family. It was hard to say goodbye, and I wept on the long plane ride over the Pacific Ocean, listening to Bic Runga’s Beautiful Collision on my discman.

The ideal candidate for a foreign exchange is someone personable and adventurous, with enough charisma to transcend the language barrier. I was none of these things. It’s funny to look back now and think what the poor Germans must have made of me. I was shy and austere, with waist-length blonde hair. I wore strange unflattering kilts and blue snakeskin flares, although at the time the TV show The Tribe was popular in Germany, so perhaps they thought everyone in New Zealand dressed that way.

My hosts were a middle-class, single-parent family. They had generously agreed to house a stranger, because they had a daughter my age and hoped we might become lifelong friends. Big mistake. Eliane was a talented athlete who slept in a cow-shaped bed and had what people back home called “mince and cheese” hair. From the moment we met, it was clear we had nothing to say to each other. Eliane and her best friend Katrin tried earnestly to include me in their friendship. But I was secretive and awkward and felt bored and alienated by their easy kindness. Even at the time, I knew this was a flaw in my own character. But I would have struggled even without the added complication of the German language.

We attended the local Gesamtschule, a drab co-educational high school, with a large running track and an enormous mural of a mouse eating a strawberry painted on the cafeteria wall. All of the teenagers wore tan pants and listened to Bon Jovi. The girls towered over the boys, who all looked several years younger. Maybe all the cigarettes had stunted their growth. Everyone over the age of 10 smoked because it was easy to buy cigarettes from street vending machines.

A few other students invited me to their parties. But I didn’t want to make friends. I already had plenty of friends back home, to whom I enjoyed writing long and pretentious emails. What I really wanted was to be a pair of eyes, floating through the world.

This proved difficult because I was a minor in a foreign country. The people responsible for my welfare probably considered me mentally subnormal and didn’t want to let me out of their sight. I think I disturbed and confused my German host family, who couldn’t understand this odd teenage girl who wanted only to eat luxurious European caramels and ride the train in silence. But in my own way, I was perfectly happy. The many small indignities and awkward social obligations were more than made up for by the secret purpose of my trip: walking around and looking at things.

I walked everywhere. I filled my eyes to the brim. I walked up the Köln cathedral, while buskers in the square below played Simon and Garfunkel on the panpipes. I walked around a family wedding in Austria, where an old man taught me to waltz by moonlight. I walked to German McDonalds and bought ein hamburger. I walked around the art gallery in the centre of town. I don’t remember a single painting I saw there, but I do remember feeling powerfully moved by the exquisite pathos of a tourist shop which sold handsome tartan umbrellas. I remember staring into the lit shop windows, bedazzled by rain, and feeling utterly electrified by the beauty of the world. It was better than a thousand Klimts to me.

I was supposed to stay for six months, but in the end, I only lasted five. I think it was Christmas that did me in. We spent Weihnachtstag at someone’s grandparent’s house, in a basement which reeked of nursing home disinfectant and secret resentments. There were raisins in the roast, and the homesickness I had been fighting off suddenly felt impossible to endure. I called my mum and swapped my return tickets for an earlier flight home.

It snowed the day I left. It felt like a consolation prize. I was given a warm send-off by my host family, who were no doubt powerfully relieved to see the back of me.

Anyone who has ever travelled knows the best part of going away is coming back changed, with an indefinable air of international sophistication. As soon as my feet touched New Zealand soil, I swapped my waist-length Brethren hair for a black pixie cut, and returned to high school, feeling worldly and invigorated, like a young Marlene Dietrich.

For years I thought my trip to Germany had been a failure. I didn’t get any of the things you’re supposed to get out of a cultural exchange. I didn’t make lifelong friends, or develop a passion for the language. But I did return with a profound and unalterable sense that I belonged to the world. Some invisible threshold had been crossed, and I felt human in a way I hadn’t before. Like the naive protagonist of a Bildungsroman, I had gone to seek my fortune and returned mysteriously altered. My German is still poor. I could probably ask for directions to the Berlin post office at gunpoint. But the most important words in any language are always the same. Hello. Please. No. Sorry. Thank you. Yes. Goodbye.