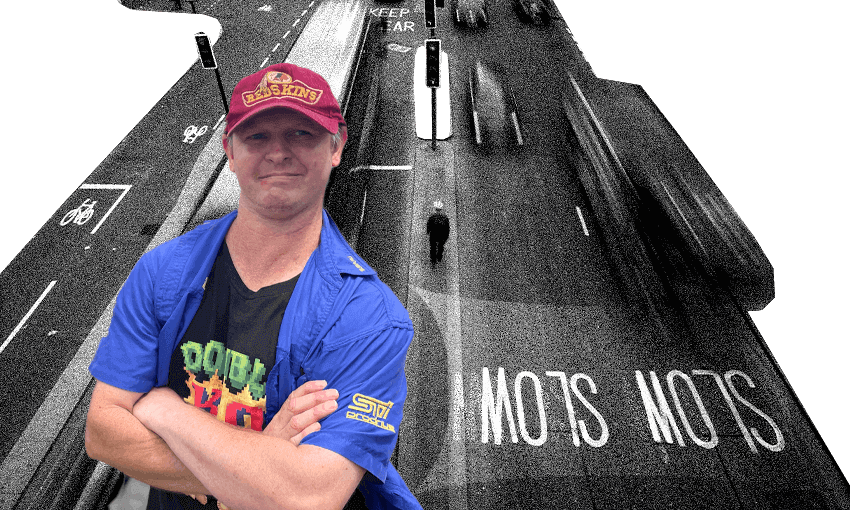

Almost four decades since he was hit by a car on a Manurewa road, Jared Ifwersen is finally seeing action.

Wattle Farm Road in Manurewa begins at the top of a hill. As you turn off Coxhead Road, past Clayton Park School, the road descends between a duck pond and an estuary, before turning into the tree-lined suburban enclave that is Wattle Downs. Population 6,048, median income: $37,000 a year.

But in November 1985, the year Jared Ifwersen was struck by a car, it was a different picture. The road was gravel, and was bordered by undeveloped farm paddocks rather than leafy bungalows.

Ifwersen was eight years old at the time and was running to meet a friend on his way to the local shops. He says it’s a moment he barely remembers, but it turned his whole life upside down. He sustained a fractured jaw, burst eardrums and intensive brain damage, with doctors giving him the grim prognosis that he would never walk or talk again. The driver was never prosecuted.

Ifwersen has not only defied doctors predictions for his recovery but has also been able to get his restricted drivers license and hold down part-time jobs despite facing ongoing side-effects related to his injuries. As we chat beside the site of his accident, the roar of speeding traffic regularly drowns out our conversation. But despite the 37 years that have passed since the incident, Ifwersen’s passion to make this stretch of road safer is still strong. And with Auckland Transport announcing it will install a raised crossing outside the school, he can finally claim a victory of sorts.

“After I was hit by a car, my mum and I have fought tooth and nail for a crossing and speed bump, as we want no child to go through what I’ve been through,” he says.

But as Clayton Park School principal Jolene Marie sees from her office window every morning, it’s really only good fortune that has prevented further accidents.

“We have been asking for eight years now [for a speed bump] and the catalyst for us has been the number of near misses we’ve had,” she says.

“In the mornings we have 10 and 11-year-olds manning the crossing, along with an adult, and we regularly see people drive through or around the signs as kids are about to cross.”

She says if there’s no one holding crossing signs, drivers speed at over 60km/hr past children waiting to cross. She’s even seen people try to hit the geese that make regular trips from their pond to the inlet.

“It’s pretty hideous, to be honest. Our staff get all sorts of abuse. It seems that wherever they [drivers] need to be is more important than following general road rules.”

Ifwersen credits Manurewa-Papakura ward councillor Angela Dalton as a crucial factor in finally getting the speed bump approved.

“Before Angela helped us, people weren’t listening and doors kept closing. But I knew Clayton Park always wanted to get a speed bump, and so I knew it was worth it to keep pushing.”

Ifwersen connected with Dalton when she was still the Manurewa Local Board chair and was impressed how she genuinely listened to his concerns, after years of being ignored or rebuffed.

Dalton says Auckland Transport (AT) initially told the board the road was “working as intended”, but after further pushing, it was acknowledged that something needed to be done.

“I’m just so pleased for him,” she says. “It’s taken forever, but like every other project at the moment, things just kept getting delayed because of reprioritisations and because of Covid.”

Dalton also points out that making use of local politicians like herself is crucial for addressing issues like this. “It really shows the importance of local residents having a relationship with their local board. AT might keep saying no, but once you get a politician involved, they will take another look at it.”

In a statement, AT spokesperson Natalie Polley said Ifwersen’s campaigning “didn’t cause the prioritisation of this project”, rather it was the school’s complaint and the organisation’s own investigation that prompted its decision.

“A request was received from Clayton Park School in 2019 for the installation of speed calming measures outside the school,” she said. “Following an investigation of the sections of Coxhead Road and Wattle Farm Road outside the school, it was concluded that the location in need of prioritised improvements at the time was the crossing facility on Wattle Farm Road.”

Ifwersen, who still lives a 200m walk from the site of his accident, isn’t fazed about who gets the credit. He’s just happy the uphill battle to make his community a little safer is over.

“I lay awake at night listening to the cars roaring down the road, so a speed bump would be the best thing ever. And while my mum doesn’t like talking about my head injury because it brings back so many terrible memories, I know it means the world to her for this to happen.”