More than 50 protests are taking place around the country today, with rural people in particular getting out to oppose the government’s environmental policy. Alex Braae went north to Dargaville.

The roads get a bit more bouncy when you turn off State Highway 1 to head out to Kaipara. Perhaps it was just because I was driving what might be the worst van in the country, but all of a sudden the shallow potholes started to look a lot more threatening.

Part of that is because the primary industries are succeeding. Milk tankers, stock trucks and logging trucks all put pressure on the roads, and constant maintenance is needed to keep them in shape. Locals believe these repairs have fallen by the wayside.

The destination was Dargaville, to report on a protest – one of more than 50 taking place around the country, organised by a group called Groundswell. They were bringing together as much as they could of the rural world – “farmers, growers and tradies” – as they put it, to protest government regulation and highlight a sense that too many costs are being imposed on rural businesses too quickly.

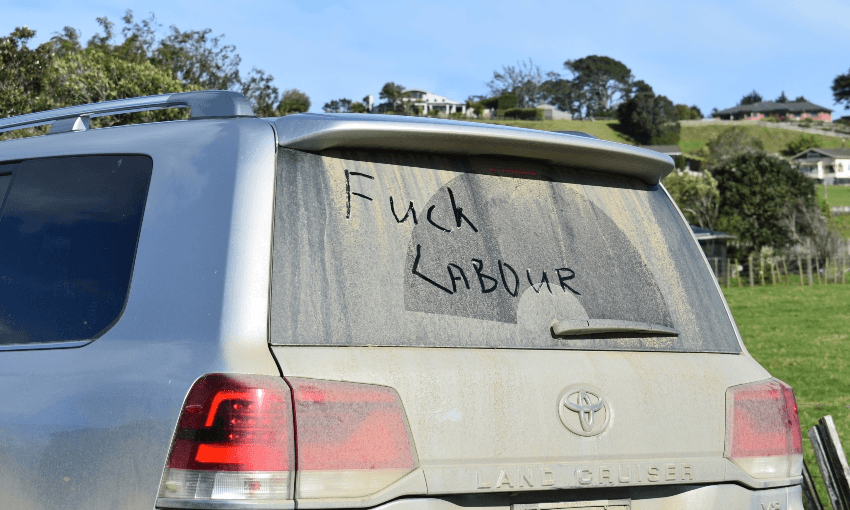

Fittingly, given the “Howl of a Protest” name given to the nationwide event, farmers promised to bring their dogs along. They also promised to snarl up the highways and byways with convoys of tractors and utes – the latter having become a petrol-powered symbol of wider rural grievance.

The “ute tax” has almost become a meme – such is the simplicity of branding of the term. It refers to the clean car scheme, which puts additional costs on the likes of a Toyota Hilux, in favour of sweeteners for the likes of a Nissan Leaf.

Decarbonising private transport is widely seen as one of the most important interventions the government can make to reduce emissions, given our fleet tends towards older and dirtier vehicles – along with the overwhelming current trend towards importing double-cab utes that will likely set decarbonisation efforts back a generation.

Nobody who only drives around Auckland’s suburbs really needs something huge and grunty. But outside of the cities, the roads can be difficult and dangerous – let alone if you have to drive on dirt roads around a farm.

Nationwide protest organiser Bryce McKenzie said people had been joking to him about bringing their tractors along to the rally in Gore, simply because the road might not be good enough to get there any other way. “Maybe a bit of an exaggeration, but once upon a time you wouldn’t have heard people say that,” said McKenzie, noting that maintenance on Otago-Southland roads had been falling away. He lives down a gravel road, as do most of his friends.

In Dargaville, organiser Colin Rowse – a former dairy farmer who now does beef cattle – said contractors in particular were getting involved in his area. “I was at rugby on Saturday and they seemed to be bailing me up more than the farmers.” It was utes in particular that tipped Dargaville attendees over the edge.

“I’ve got a mate who owns a logging company, and they run 52 utes. So this is going to cost them a lot of money, especially in three or four years’ time. You know, you’re just thinking ‘what the hell?’”

Rowse admitted it wasn’t just a work thing – utes are also a status symbol for many. “There is a bit of a trend for young fellas at the moment to get a ute and make them look cool – you know, big tyres and suspension and that.”

Every man and his dog getting amongst

Groundswell was formed last year in the area around Gore, said founding member McKenzie. It originally related to the government’s drive on freshwater quality legislation, and the conditions that were imposed on land users to make improvements. McKenzie saw that as insulting and “absolute rubbish”, as a member of a group that since 2014 had voluntarily been cleaning up the Pomahaka River, which has since shown improvement.

Political parties made a big effort to attach themselves to today’s events, but organisers sought to keep them at arm’s length. Act announced the entirety of its caucus would be attending, and National announced the same for the vast majority of its caucus. Judith Collins even promised to drive to the Blenheim protest in a ute, dragging a digger.

Bryce McKenzie said MPs were welcome to attend the events across the country, but would not be invited to speak. “All our coordinators know that politicians are there to listen to the people, but not talk to them.”

“Well, they can talk to them privately, but they’re not getting a microphone,” he added.

Also attaching itself to the events is a more conspiratorial-minded outfit called the Agricultural Action Group. Where Groundswell sees government policy as an overreach, the AAG sees it as something much more sinister – a socialist, big government takeover. In fairness, it isn’t unusual for extremists to attach themselves to more moderate protests, no matter what the cause is.

McKenzie was very clear that the AAG had not been involved in the organisation, but acknowledged they had been promoting the protests through their own channels. “They’re involved in spreading the message about it, we certainly know who they are, but we’re not aligned with them,” said McKenzie.

“They say a lot of good things, it’s just some of the things [they say] that we probably stand a wee bit distant from.” He added that “we actually prefer to not go too extreme”.

The only group outside Groundswell that’s directly involved in organising is the Rural Advocacy Network. Federated Farmers has shown muted support for the event, and some organisers are members, but it isn’t their show. In the online commentary leading up to the protests, it quickly became clear both that the protesters didn’t speak for everyone in the rural world – but also that there would be significant differences of opinion within those who decided to get involved.

A day out in Dargaville

There were two things on the mind of people who showed up at Pioneer Park in Dargaville. Apart from the protest, the people were fizzing about the local rugby team. The Sharks are about to play their first premier grade final in 11 years, and hopes are high that the busloads of supporters going up to Whangārei will come home with a trophy.

In all, local organiser and National Party activist Grant McCallum counted 198 vehicles, and about 350 people on the field to listen to the speeches. They were kept short and sweet, with the people’s presence intended to speak for itself. Rowse spoke briefly at the start to thank people for coming along, before McCallum read out a statement on behalf of Groundswell.

People had taken a day off from a variety of jobs, and a range of issues came up when talking to them. For Sue Reyland, the topic on her mind was the SNA (significant natural area) legislation that some farmers believe amounts to a “land grab”, with onerous new rules on what they can and can’t do with their property. SNAs are aimed at halting environmental degradation and biodiversity loss.

Reyland owns a farm near the Kaipara Harbour, and showed off pictures of a beautiful area of beach at one end. She said her family had owned it for 130 years, and throughout that time had kept swathes of it natural and undeveloped. “We feel we’ve looked after it, haven’t abused the land,” she said. But she feared a loss of control if SNAs were put in place – for example, she and her husband won’t be able to put a bach down at the beach.

She has been involved in political activism for about a decade, particularly around local roads. Her campaigning was part of the reason why National, in the 2015 Northland by-election, promised 10 new bridges for the area. Since then she has also started a “freedom of expression” Facebook page, which was sparked by a call from the police after she made a joke online about taking Labour MP Phil Twyford hostage, which she says was taken completely out of context.

Reyland was adamant that the organisers of the protest were right to stress that it be a peaceful and good-natured event. But she also hinted that patience with playing nice was starting to run out.

Meanwhile, dairy farmer Bronwyn Williamson was “just bloody over it”, saying it was “just everything” the government was doing that brought her along. She said government MPs “don’t have a clue what farming is about, and they’re trying to make all these rules that are absolutely unworkable”. She too talked about how farmers were “all doing our own things” to protect the environment – in her case pest control and possum trapping.

“Urban is so disconnected,” added Williamson, reflecting a wider mood at the protest that rural voices aren’t being heard in Wellington.

The protest also attracted people who might have taken any opportunity to have a crack at the Labour government. There were a few signs promoting the Voices for Freedom group, for example, which pushes conspiracy theories about vaccines, and sees the government as dictatorial.

But above all, the protest was economic. Groundswell included a note that they hoped people would go and have lunch in the many service towns hosting events, to put a bit of money into the economy. That was a counterpoint to the argument of the protesters, that government policy will end up taking money out of the regions and into the cities.

“We’re all legitimate ute users, and we’re going to get penalised by this $3,000 immediately, and most of that money we’re never going to see,” said Rowse.

Will the protesters get their way?

Despite the protests happening in so many spots, the government appears unlikely to be swayed. Environment minister David Parker told Newshub “are we going to back away from our commitment to have rivers that are swimmable? No.”

It isn’t necessarily a difficult protest for Labour to dismiss, with the political map being what it is right now. They won a huge mandate at the election, completely control parliament with a healthy majority, and can be sure that plenty of their urban voters will see these protests as ridiculous.

But the 2023 general election isn’t the only vote coming up, and the widely popular prime minister Jacinda Ardern won’t be on the ballot for local elections in 2022. Smaller but more committed groups can do exceptionally well in local elections if they organise, and the success of these protests indicates there are rural networks in place that can mobilise people quickly.

It’s all happening against a backdrop of central government trying to renegotiate the relationship with local government – which many observers would argue is a sweeping exercise in centralising power. The water infrastructure reforms, for example, will require goodwill from councils to go ahead, and there’s a huge political risk for that programme from councils fighting tooth and nail to prevent them.

“I just want to make apologies for [Kaipara mayor] Jason [Smith],” said Rowse in his speech. He would’ve been here with bells on in his legitimate ute, but he’s down at the local government conference.” McCallum also made a shout out to Grey District mayor Tania Gibson, who has thrown her support behind the protests.

Groundswell is likely to keep pushing. It included in its statement a demand that the government announce a change in course by the middle of August, or else there would be more protests.

On the way out of Pioneer Park, a huge queue of utes, tractors and trucks built up quickly. The plan was to do a careful loop of Dargaville, before dispersing back across the region to the smaller towns and farms.

At the turnoff into town, traffic had slowed to a crawl. The intersection was completely clogged. It served to show that when rural people get organised, they’re capable of shutting things down.