Beaten for speaking the language; shame around speaking it; suppressed and ridiculed by the British. Sound familiar?

Welsh is a dead language.

This is what I’ve been hearing my entire life.

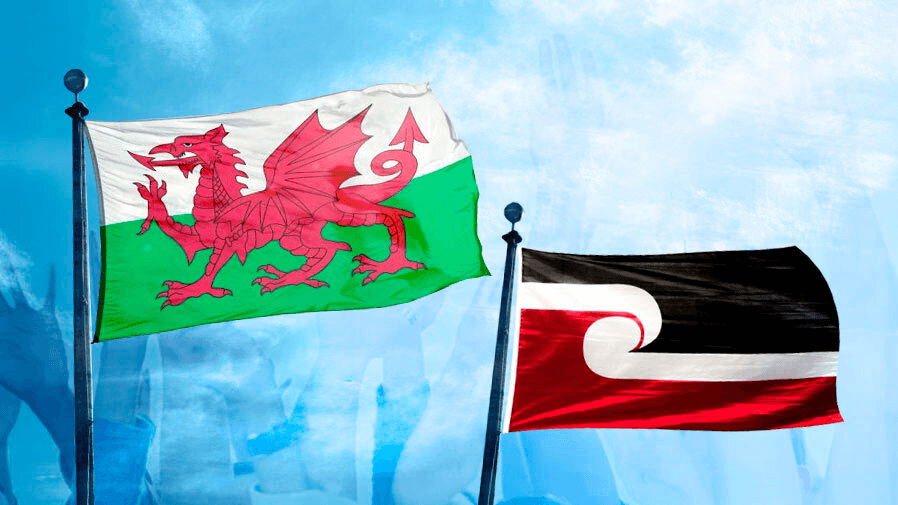

I’ve always been aware of the comparison between my language and te reo Māori. Both, I knew, shared the precarious position of being endangered languages.

I was surprised, then, to read this article looking to Wales with admiration for its handling of the language.

Growing up, I would never have confessed to enjoying Welsh language music, television or books. I made a point of not being seen with the patriotic Welsh kids, and spoke to friends in English despite knowing we both spoke Welsh at home.

Wales became the first English territory way back in the 13th century, before being officially incorporated into the kingdom by Henry VIII in the 16th century. While the Celtic name for our land, Cymru, refers to “friends” or “fellow countrymen”, Wales derives from an Anglo Saxon word meaning “foreigners” or “outsiders”.

I learned how Welsh was literally beaten out of school children by none other than Welsh teachers, led to believe by a government commissioned report — known today as the Treachery of the Blue Books — that “the evil of the Welsh language” posed “a manifold barrier to the moral progress and commercial prosperity of the people”.

Any child caught speaking Welsh was humiliated by the wearing of a heavy wooden plaque around the neck, reading WN or “Welsh not”. The child left wearing the plaque at the end of the day was physically and psychologically punished.

It was a real shock, then, to find this video of Jemaine Clement breaking down as he said his kuia would be punished for speaking te reo. Just like us, generations were robbed of the language of their ancestors.

I grew up with the mantra “Cofiwch Dryweryn” — Remember Tryweryn — which memorialised the Welsh-speaking village of Capel Celyn, drowned in 1965 to provide England with drinking water despite vehement opposition from villagers and MPs.

I grew up hearing how the English “subsidised” our language, as if my people didn’t pay our own taxes.

I grew up hearing how we have no vowels (we have seven) and about that one pub no one can ever name, in which every local stops speaking English as soon as an Englishman walks in, just to spite him.

British is an identity that has been forced upon me, so I feel privileged that Welsh was compulsory throughout my schooling, instilling in me a belief that my mother tongue was just as valid as English. It helped me connect with my culture and grounded me in my own history.

Outside school, Welsh was (legally, at least) treated with equality. Largely thanks to efforts by Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg — the Welsh Language Society — we had bilingual road signs, television and correspondence, and it was recently announced that basic Welsh will be required for new Welsh government jobs. The Welsh Assembly has even set itself the target of achieving one million Welsh speakers by 2050.

Seeing my language treated with respect makes me feel proud and supported, even when the London-centric British media and government treat it with ridicule or outright contempt. We sympathise with Māori who are dealing with hysterical “stop ramming it down our throats” narratives – a boss within our National Health Service actually compared the treatment of non-Welsh speakers to that of Black people during South African apartheid.

One of the challenges we face is that Welsh-language heartlands are being decimated as properties are bought as second homes, exacerbated by the pandemic which showed city-dwellers they could work from anywhere with an internet connection. Young people like me can’t compete with outsiders paying over the odds for properties, sight unseen, that push us further and further away from the communities we grew up in. I joined thousands this summer in protest on the shore of Tryweryn dam to declare “Nid yw Cymru ar werth” – Wales is not for sale.

Trademarking and appropriation also pose a threat to our language. A Welsh clothing firm was recently banned from using the name of our tallest peak because it had been appropriated by an English lifestyle brand.

We may seem aspirational, but Wales still has plenty to learn from Aotearoa.

While Māori are reclaiming the original names of places like Taranaki, Welsh names are increasingly disregarded in favour of twee, tourist-friendly translations with no connection to our history.

I am fascinated by the defiant use of te reo in English-language text and television, and how Māori and non-Māori New Zealanders are falling over themselves to enrol in free te reo lessons. There is even te reo Disney! Aotearoa seems like a utopia, but I know that the history, like ours, is fraught, the gains were hard won and that much hurt remains.

Our situations are similar but they are far from equal. I have to acknowledge that the colonised can also be the coloniser; I have undoubtedly benefited from my ancestors’ entry into Aotearoa, while racism and colourism add an extra layer of complexity.

Nevertheless, I take heart in knowing we’re in good company. Happy Te Wiki o Te Reo.