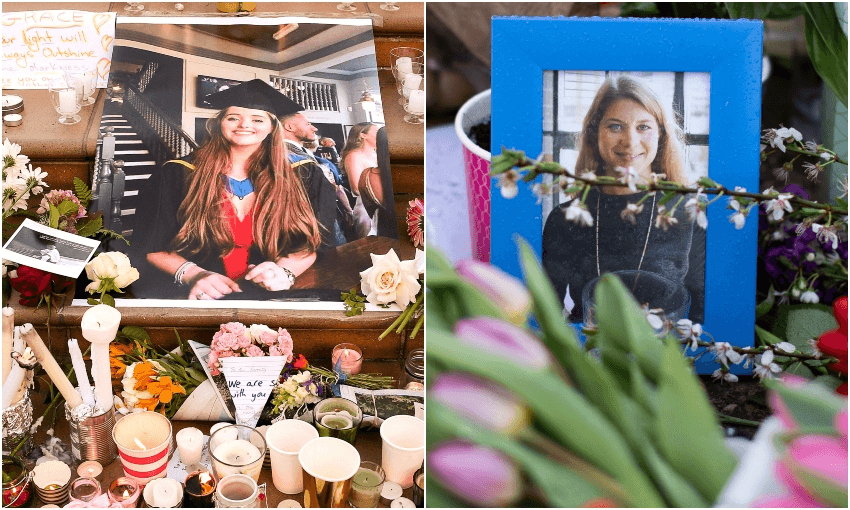

The death of UK woman Sarah Everard earlier this month has led to an outpouring of grief and rage, in the same way Grace Millane’s death did in New Zealand. Laura Walters looks at the similarities between the two cases, and how they’re changing the narrative on male violence.

When UK backpacker Grace Millane was killed in 2018, New Zealand mourned.

We mourned Grace, and the life she wouldn’t get to live; and we mourned all the other women who had died at the hands of men. Amid that grief was outrage that women continue to be coerced, abused, harassed, assaulted and killed, while being told the responsibility to stay safe falls to them.

Women shared their experiences, pushing back at attempts to place the blame on victims like Grace. And the voices of those who’d previously been denied a platform were put at the centre.

Of course, this progress needs to be seen in the context of the country’s disproportionately high rates of sexual and family violence. But as the public rhetoric changed around the case, so did the framing of gendered violence in the media, and among politicians.

We stopped focusing on the actions of the victim, and on how we, as a society, were implicated in Grace’s death.

Now, the same shift is happening in the United Kingdom, following the murder of Sarah Everard.

When the 33-year-old marketing executive went missing while walking home earlier this month, London’s Metropolitan Police told women to stay indoors. Like Grace, Sarah was performing a blameless task when she was allegedly abducted and killed by a serving police officer.

Women saw themselves reflected in Sarah, and while they mourned her, they also felt a profound outrage at the constant threat women face.

When police told women to stay home, told them abductions were rare, and then tried to silence those gathered to mourn Sarah, women pushed back.

It’s been more than 40 years since the first Reclaim the Night march, which was prompted by the Yorkshire Ripper murders and the police response, telling women to stay home after dark. And the dynamic has finally shifted.

During the past fortnight, thousands of women have talked about the realities of walking home alone, and the freedoms they’ve lost just by being born a woman. And, as happened in New Zealand following Grace’s death, the issue is gradually being reframed as a societal matter about male violence and systemic misogyny, rather than an isolated case created by individual circumstances.

The attention

Victoria University of Wellington criminology lecturer Sarah Monod de Froideville said the deaths of these two women caught the public’s attention because of who they were and what they were doing.

Firstly, they both fitted the criteria of an “ideal victim”.

The concept, created by Norwegian criminologist Nils Christie, identified the “ideal victim” as weak in relation to the offender, and at the time often undertaking a blameless task – either routine or benevolent work – such as going on a date or walking home. In real terms, these victims were usually young (or elderly), female, attractive, Pākehā, and middle class.

The events of both cases also lent themselves to the “classic cautionary tale”. It was an opportunity to tell a real-life version of Little Red Riding Hood, which served to teach small girls, and remind grown women, they were not safe in the world when alone.

“And they are not safe in the world alone because it is one oriented to protect male interests,” Monod de Froideville said.

Durham University assistant professor of sociology Fiona Vera-Gray said Sarah’s death “really touched a nerve in a way that previously this kind of violence just hasn’t”.

Both women felt familiar to many of those in positions of power, such as politicians and media, she said, adding that the familiarity helped people see these victims as blameless. “They represent the women that you know, and love, and are.”

Vera-Gray said people were increasingly focused on assaults perpetrated by strangers, or those involving gory details. She put this down to the popularity of the true crime genre, and its sensationalisation and glorification of violence against women and girls.

The idea you could be going for a walk, or on a date, and be killed by a stranger in a horrific way, fitted the model of violence against women shown in entertainment.

Vera-Gray said society needed to broaden its way of thinking about violence against women to include less sensationalised forms, such as coercive control and family violence. “We need to focus on the humanity of the victims. And not focus on the gory details.”

While these features may have been at play in grabbing the public’s attention, they in no way dismissed the rage and grief over the loss of the two women, Vera-Gray said. “At the same time, we should be keeping that level of outrage when we hear about all women.”

The pushback

Victoria’s Monod de Froideville said the pushback against the usual victim-blaming and “cautionary tale” had a lot to do with the #MeToo movement. #MeToo connected the dots between women’s experiences across multiple divides. It created a “levelling out” and an “awakening”.

“It shook us out of our complacency and was a wake-up call that gender equality has not been achieved, is not here, and that there is still a long, long road ahead before we get there.”

It was also the first time a rights movement has had a platform that offered instant, global reach, Monod de Froideville said. “It is like #MeToo let off the safety valve of a loaded gun.”

Vera-Gray said having these conversations play out online allowed a space for women’s voices, and shared experiences, to be heard. Especially those from marginalised communities.

“When millions of people, worldwide, are saying this happened to me too, it becomes difficult to see this as an individual issue.”

Vera-Gray said the state of the world also had a part to play. Sarah’s murder was “a smack in the face” after a year of lockdown.

For the past year, people had been told they couldn’t go outside due to Covid-19. Now they were being told it was unsafe for women to go outside because of men. “And instead of feeling that inarticulable and unplaceable rage, they used social media to put their stories out.”

The media coverage

The media has a poor track record when it comes to covering stories of violence against women and girls. Part of the UK’s 2012 Leveson Inquiry into press standards – following the News of the World scandal – examined the salaciousness the press applied to stories about gendered violence.

A submission from a group of women’s organisations said much of the newspaper reporting about crimes of violence against women promoted and reinforced myths and stereotypes about abuse (such as “real” and “deserving” victims, “provoked” or “tragic” perpetrators).

“It is often inaccurate; and does not give context about the true scale of violence against women and girls, or the culture in which it occurs.”

Analysis of a typical month of news coverage at the time showed 78% of newspaper articles were written by men. The statistics were similar for television and radio contributions.

Meanwhile, a 2019 New Zealand study found coverage of violence against women in the mainstream news media was extensive, but explicitly situating violent experiences for women within a broader social context was infrequent.

Few news reports included information on where to seek help, and they rarely elevated the voices of survivors, advocates and other experts.

There has been some movement in both countries over the past couple of years, largely thanks to decisions made by individual women journalists, and reporting on #MeToo stories.

But the notable shift in New Zealand came in the wake of Grace’s murder.

Monod de Froideville, who is researching media coverage of Sarah’s case, said the media made a significant departure from the way they had previously reported on male violence. Female reporters openly refused to write stories that reinforced victim-blaming or the cautionary tale. And women’s voices were centred in reports, rather than those of male lawyers, politicians and “experts”.

“Women decided they were not going to tolerate media stories that tell them cautionary tales any more no matter how much they appear in the guise of ‘common sense’,” she said.

In the past week, the UK media has begun the same shift. Mainstream organisations like BBC are now talking about “male violence against women”, as opposed to “women’s safety”.

Vera-Gray said it was the first time she’d seen this framing in her 20 years of working in this space. “There is a much greater ability of the public to tell media what stories we will accept from them,” she said. This comes both through social media feedback, and the power of clicks.

There was a long way to go in addressing male violence, especially in terms of policing and meaningful political response. But the grief, outrage, and educated discussion happening in the wake of Sarah’s death has given Vera-Gray optimism.

“There has been a shift from, ‘what was she doing’ to ‘what are we all doing; how are we implicated in this’.

“And what can we do individually to change some of the things that we do every day that supports this culture that enables men to use violence against women,” she said.

Where to get help:

- Safe to Talk sexual harm helpline: 0800 044334, text: 4334, email: support@safetotalk.nz

- Rape Crisis: 0800 88 33 00

- Women’s Refuge: 0800 733 843

- Shine domestic abuse services free call: 0508 744 633 (9am and 11pm)

- Hey Bro helpline supporting men to be free from violence: 0800 HeyBro (439 276)

- Family violence information line to find out about local services or how to help someone else: 0800 456 450

- Shakti – for migrant and refugee women – 0800 742 584, 24 hours