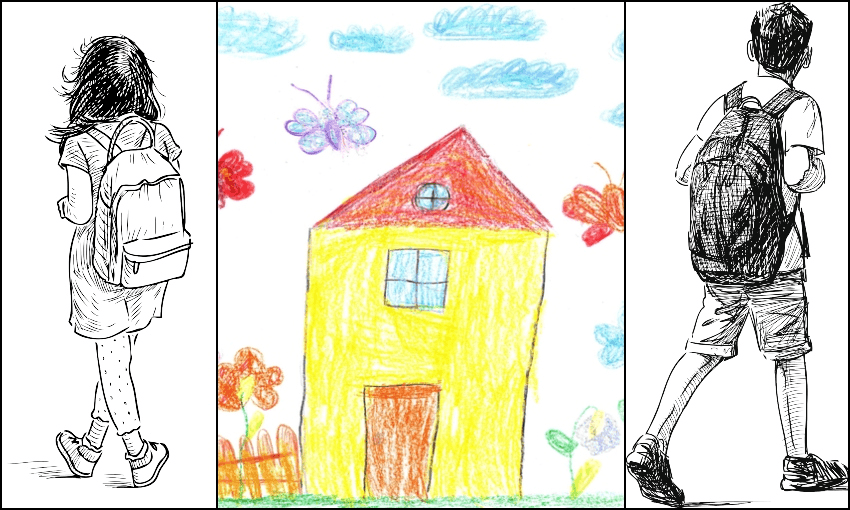

Catherine Woulfe’s son’s school is nothing fancy. But it’s theirs. Auckland’s new zoning rules will mean her daughter, when she turns five, will have to go to a different one – and that’s heartbreaking.

I just saw a map that puts us 100 metres out of zone for the primary school my son’s been at for two years. It’s an absolutely stock-standard state school. Diverse, with a roll of about 460. Decile four back when we still talked about deciles. Nothing wrong with it, nothing fancy either. But this is our school. It’s right next to kindy and daycare. It’s the school my son loves, the school my daughter toddles through cooing “skoo”, the school we assumed she would be part of, in a few years. But now we’re all but certain: she won’t.

Right now this school is not zoned. It takes all comers. But it is already overflowing and that’s without counting the huge development going in just down the road.

When the zoning kicks in later this year the first spots will go to families who live inside the magic lines on the map. Those kids get first dibs – even over siblings of current students. If the school doesn’t fill up then siblings might squeak in through a ballot system. But if the school does fill up – as we expect it to – then sorry, that’s it.

So the map I saw this morning is a map that says to our little girl: no. You can not come here. Your brother can stay, if he likes, but not you. And what that feels like is a message to the whole family: you are not welcome.

*

When you join a school you join a community. Or you follow one. We chose this school because Ben’s little gang of mates from kindy were headed there. We wanted to stick with their families, too – these are the parents we’ve been with since our kids were tiny, through Playcentre sessions and kindy drop-offs and vomiting bugs and first steps. These women have rubbed my back as I miscarried. They’ve held my sobbing boy. We’re well past the small talk, and thank god.

So we chose this school. And it’s nothing fancy, but it has kind receptionists, the sort who make you feel totally fine about fucking up all the paperwork or not knowing you were meant to buy a bookbag. It’s not fancy, but one day I stumbled into the office with my screaming new baby and they all but tucked me in for a nap; I remember breastfeeding on the couch and looking at the steamed-up windows and feeling so happy we’d found a good place for my boy. It’s not fancy, but I can’t describe what it felt like when Ben’s teachers dressed up and danced like twits to ‘Don’t Worry Be Happy’, and sent the video out on the hardest, scariest day of lockdown.

When we joined this school we joined a community, and although what’s happening is not the school’s fault, it is a very primal thing to be kicked out of it.

I am emotional. I am entertaining wild ideas. Maybe we sell the home we’ve been in for 10 years, the place with the huge willow and my cat’s ashes and my boy’s whenua, and buy in-zone, ie across the road? Maybe we pull a Grammar and pretend the kids now live in-zone with their granny? Maybe we switch Ben into the perfectly good school we’re about to be zoned for? But I can’t see how pulling a six-year-old away from his friends is any kind of solution. Especially after the disruption they all went through last year.

I can’t stop thinking about how hard it was for us to have Leo, how the age gap of nearly five years was always going to make it harder for our kids to be friends, but being at different schools … we knew that zoning was coming, but naively we assumed siblings would get automatic access. We only just realised that in a city under pressure that’s not how it works. We feel blindsided. How did we end up with a school system, with a social infrastructure, that splits up siblings when they’re five and nine?

As the hurt wears off I will start to be properly pissed off about the pragmatics. Two logins for the clumsy app that schools use to keep in touch. Two sets of teacher-only days to work around; two sets of assemblies and prize-givings, school plays and dances, dress-up days to remember, fun runs, two school galas (gaaaah). Two sets of school drop-off and pick-up.

Our house is smack in the middle of the two schools. Each one is about a 15-minute walk up a hill. There’s no way you’d walk that loop with two kids in tow. This is a small thing, but also not: I really, really wanted to be able to walk my kids to school each day. They’re knackered by the afternoon. That morning walk is a chance to hang out when everyone’s at their sweetest. For them to hang out together.

*

The more I think about it the more I’m convinced that what’s about to happen across Auckland (while well overdue, logistically) is a kind of societal carnage. New zones are getting dropped on schools – on families – all over the place. Communities are about to be carved up and that will blow back on schools, which can only work well when their whānau feel engaged, as well as on families. Because these changes simply have to happen consultation is likely to be piecemeal, a hollering into the wind. Many families, like us, won’t have had to deal with zoning until now: this is not simply a matter of tweaking lines on a map, it’s borders thumping down where there were none before.

So many parents will be left running the what-if maths: will my rent go up? How do I stretch the petrol budget? What if my landlord kicks me out so his kids can get in-zone? How do I possibly manage two full sets of uniform?

More visible will be the never-ending story about what zoning is doing to house prices. Hottest new streets, revealed. Zoning shock: the house that lost $100,000 overnight. I want to be clear that my reaction to what’s happening in our neighbourhood has nothing to do with what’s happening to the value of our home. If you bought a house 10 years ago in Auckland you do not get to fret about property prices.

We deliberately bought in an area with no zoning because we were repulsed by the whole scramble, the gross rich-get-richness of it all. So as a crash course, I’ve been reading the guidelines that the secretary for education produced for all the schools trying to get to grips with zoning. The document was only released in December but it reads like a story about somewhere else, a long time ago. What it taught me is that zones and the rules around them are set up for people with the immense privilege of staying put. It’s not a system for those in most need of a welcoming community: those who’ve been buffeted by Covid, by Auckland’s cataclysmically hot property market, by trying to find – and then hang on to – a decent rental, or a job. It’s not set up for fluid families, where children are sent to whoever’s best equipped at the time, or for broken families, unless you’re the kind who break in organised, documented fashion. It’s not set up for families forced to cram into homes with other families, or for those who don’t have the resources to navigate what’s now going to be an acutely stressful enrolment process.

Seriously, brace for things to get invasive. “Schools have found documents such as power bills, bank statements, rates demands, leases or tenancy agreements and statutory declarations to be useful in the past,” the new guidelines say. “Experience has shown, however, that not even these documents will necessarily provide evidence of ‘genuineness’.”

Further tips for schools: check whether an in-zone house looks “suitable” for a family to really be living in. If a child is living with their grandmother in-zone, find out whether there are “special family circumstances” behind the arrangement – or do they just want into your school? Get in touch with landlords to find out more about their tenants’ circumstances. Say a student has just moved into the zone to live with his dad: check the place out, if it’s a one-bedroom flat, definitely raise an eyebrow. Keep a list of all the families you have “suspicions” about, even if you can’t prove they’re lying. Yet.

So much prying, so much grey, so many judgements that will come down to the character of the poor sod each school puts in charge of gatekeeping. And as I read through all of it, this whole bleak document, I keep picturing walking down our drive with my kids, and waving my son off on his trip to school, and turning to head the other way with my daughter.