What possesses someone to drive around with a pair of bollocks dangling below their towbar? Gabi Lardies investigates.

It started on a crisp walk in a leafy central Auckland suburb. Something red and dangly caught my eye. The item in question was hanging off a parked car’s towbar, and upon inspection, didn’t seem to be attached to anything useful.

The more I looked, crouched down behind the unsuspecting sedan, the more I failed to see how the plastic object, uncannily similar to a ballsack, could be a part of the engine. But what do I know about testicle shaped plastic or engines?

Months later, on a cold evening in Dunedin, a friend mentioned those “ridiculous nuts” people attach to the back of their cars. “I’VE SEEN THAT,” I said, thinking I was special. “What the hell are they for?”

Stupid question. If you’ve seen them, that’s their purpose. Truck Nuts, sometimes stylised as Truck Nutz, are an aesthetic car accessory. Their resemblance to a ballsack is entirely on purpose. If they’re not for anything, then I’m left with the questions of how and why.

Like so many great and questionable things, they originated from the US. In the 80s, home-made nut sacks began appearing on the back of utes, driven mostly by rural white working-class men. Some of these early iterations are abstracted enough to be visually appealing, for example two extra large steel nuts threaded through a chain. It wasn’t until the late 90s that moulded plastic Truck Nuts became a product (with two companies going to war over who made them first).

It’s impossible to say how many Truck Nuts are now gracing the streets of Aotearoa. They are easy (though surprisingly pricey) to buy online. An unscientific survey of my Instagram followers confirmed Truck Nuts have been spotted in Titirangi, Morningside, Grey Lynn, central Dunedin, on a wheelchair and on vehicles “parked in our driveway without asking”.

Truck Nuts have even made it into lecture theatres at the University of Auckland. One slide in an introductory course to social geography is covered in photos of nuts on trucks, and their owners sitting on the back so that the nuts appear to be theirs. “It has quite a good shock value,” explains Salene Schloffel-Armstrong, geographer and professional teaching fellow. Apart from providing comic relief, she uses Truck Nuts to illustrate the performance of gender. “It lends to thinking about masculinity as more ridiculous than maybe they have before.”

“What is that desire to put nuts on your car?” asks Schloffel-Armstrong. She doesn’t think there’s a single answer. “You can read them as a performance of a particular masculinity, which could be somewhat binary and problematic, or something that’s nonsensical and surreal and ridiculous”. In other words, where does ball-worship end and irony begin?

One Aucklander got Truck Nuts and headlight eyelashes for her birthday a couple of years ago. They were a gag gift, “for a lol”, but were put on her baby blue Nissan March on the spot, and stayed there until she upgraded her car. “People would definitely react worse to the eyelashes because they were giving ‘very bimbo idiot woman’,” she says. Judging by the reactions of other motorists, the veiny ball sack on the back was less offensive. Her new car has no adornments.

One US Truck Nutter, Tyler, who has had green Truck Nuts on his green ute for eight years, spoke about his choice on the Decoder Ring podcast. “I revel in the trashiness of it, I think that’s part of the humour,” he said. When he stops at red lights, he can hear the balls rattling on the back of his truck. “I get a chuckle to myself.”

But while he may be having a private joke, the nuts are on public display. They’re born of a culture infamous for being racist and sexist, and one which has used other car accessories, like bumper stickers and mudflaps, to be provocative and offensive. Some say that Truck Nuts became more popular in the US when there were attempts to outlaw them – they became an issue of free speech. Perhaps macho Truck Nutters are laughing, but could they be performing that dominant toxic masculinity at the same time?

Unable to get to the bottom of the phenomenon via Google, academic experts or Truck Nutters themselves, my only remaining option was to try them out for myself. New Zealand based Truck Nut stockist Not Socks thanked me for my particular interest, but said they were out of stock – they’ve stocked them for a few years, but usually only for Christmas. Instead of waiting for international shipping, I decided to tap into Truck Nuts’ DIY origins.

At 9.07pm on Wednesday night I began rifling through the misc drawer in my kitchen. There was a white plastic bag and two potatoes which could be put inside, but the end result looked more like a doggy poop bag than testicles. “What can I use to make Truck Nuts?” I asked my partner, who has more intimate knowledge of both nuts and trucks than I do. He went to the misc box on top of the cupboard, and pulled out a bag of party balloons. Partially filled with water, two orange balloons became beautiful, bright, slightly saggy orbs. Perfect.

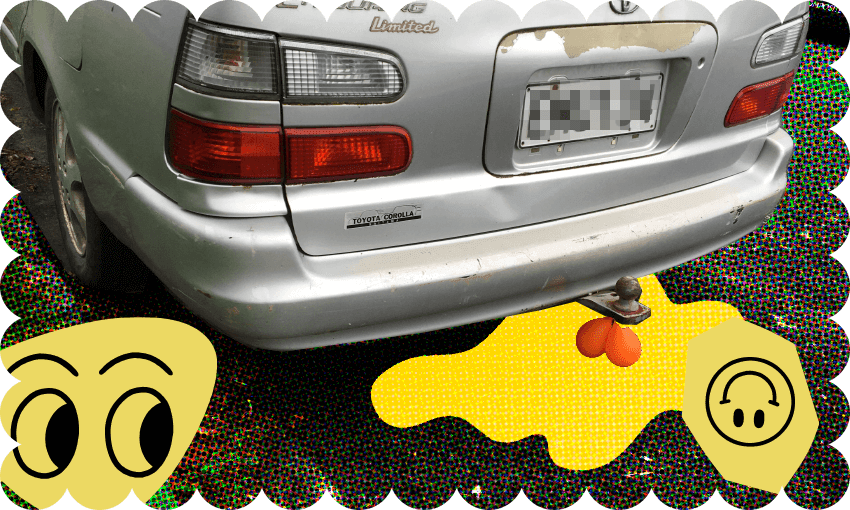

The next morning, I tried my Truck Nuts to the tow bar of my 1998 Toyota Corolla L-Touring Station Wagon, and embarked on a tour. Truck Nut stockists always make a point of describing their nuts as being strong and hardy, which is not two words that come to mind for balloons. I felt precious about my dangling balls – what if a piece of gravel or a shard of broken glass flicked up and popped them? I was hoping to feel their sway like Tyler described, but even though they’re pretty big for balls, I felt nothing.

I drove slowly and gingerly through Mt Eden to Symonds Street, the domain of Schloffel-Armstrong and her students. It was rush hour, but no-one tailgated me. I tried to find shocked faces in my rearview and side mirrors, but everyone looked otherwise occupied.

I was wondering if I looked tougher than usual when a white Mazda SUV undertook me and cut me off as I was indicating a lane change. No one was pointing or laughing at me, even though students are known to point and laugh. I made my way towards Queen Street, cautious of the many manholes. Truck Nuts are very ridiculous car accessories, but in some ways they are subtle (small, at the back and low down). Choosing to drive the biggest possible ute, having chunky tyres, attaching a spade somewhere onto its exterior (we all know it could easily fit inside) are also performances of macho masculinity – maybe if I had the whole kit and caboodle I might feel like a tough guy instead of someone scared of popping their nuts.

As Queen Street approached Karangahape Road, some small butterflies of shame or embarrassment stirred in my stomach. It is highly likely there are people I know here. I wanted to pull my hoodie over my head, but to be a good driver one needs peripheral vision. Luckily the route to Ponsonby Road passed without incident. Perhaps my balls, with no pubes, wrinkles or veins, were too beautiful to offend people. Or I simply couldn’t see the wake of disgust and amusement behind me.

On Ponsonby Road, an Inner Link bus showed up in my rearview mirror. Could my two orange bouncing orbs bring joy to a bus driver on a long shift? When I checked, he was staring straight ahead, bored out of his mind. If only he had looked downwards. When I ended my tour outside The Spinoff office, my orange nuts were intact and perfectly plump – undamaged by their tour of Auckland’s roads.

Then an Instagram notification popped up on my phone. At least one person had noticed my Truck Nuts.