‘On one scale the coronavirus that plagues us is microscopic. On another we ourselves are made small.’ An essay by Alex Kazemi.

Make a Moebius strip. Take a long rectangular piece of paper, loop it, then join the two ends after putting one end through a half twist. The resultant shape is three dimensional but one sided. A small ant starting at one point on the strip can walk perpetually forwards, tracing the exact same route over and over whilst seeming to change sides.

Our stories loop too. Another wave of the pandemic has receded into optimism again here, but these times globally seem newly oppressive. The decisions we face are ones we have seen before though, in other guises.

In May 1720 the ship Grand Saint-Antoine arrived in the waters of the port of Marseille. It returned from a long journey to the Levant, trading at the end of the Silk Road. Its cargo was worth a hundred thousand crowns but would also, within the next year, cause a hundred thousand deaths, in one of the last great outbreaks of the Bubonic Plague.

Until then Marseille, and France, had been largely free of plague for decades. The city had a system of lazarets, quarantine islands, to isolate ships that had travelled to plague affected ports. A Health Authority had also been established to oversee the quarantine system, independent of the masters of the port and reporting directly to the City Council, the deputy mayor of which was Monsieur Jean Baptiste Estelle, the owner of the Grand Saint-Antoine.

All our choices are made in a machine of many interlinking cogwheels, most of them hidden to us. A turn of each and fate clicks into place. The Grand Saint-Antoine arrived at the time of the Fair of Beaucaire, being held less than a hundred kilometres from Marseille. In its time this was the largest market in southern Europe, a forum for the goods brought in from the East. Trading at the fair was a lucrative business.

En route to Marseille from Syria one of the passengers of the Grand Saint-Antoine had fallen sick and died. Although several more sailors died on the ship subsequently, it still made its way to Marseille. When the ship arrived, it and its crew were held at one of the lazarets but deputy mayor Estelle, eager to offload his ship’s goods to send to Beaucaire, exerted pressure for the cargo to be brought ashore prior to the end of the statutory quarantine period. Cloth infested with plague-carrying fleas was stored in warehouses in the working class neighbourhood of the city, where sanitary conditions were poor.

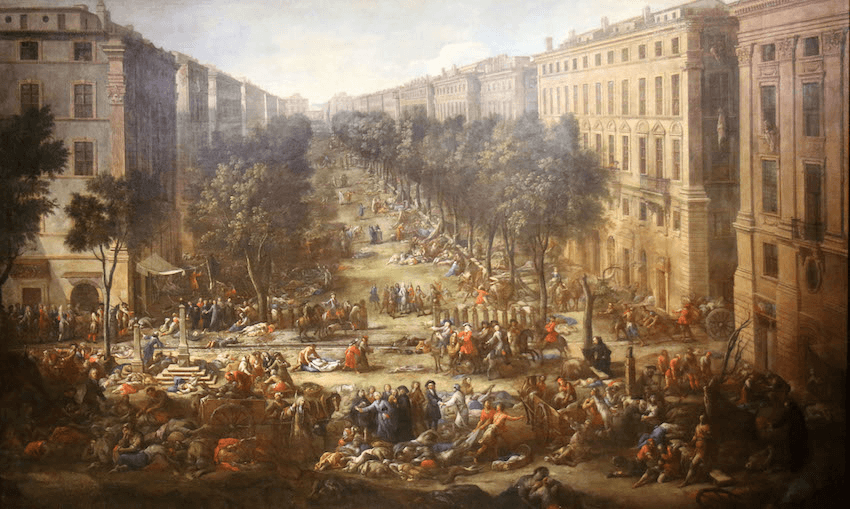

The first case of the plague in Marseille came in June but by the end of July it had spread throughout the entire city, carried darkly through the shadows by fleas and scurrying rats. At its peak, after the Grand Saint-Antoine was burned and sank off the shore of the city, it caused hundreds of deaths per day. The spread was compounded by the indecision of the authorities and hesitance to declare a state of emergency, instead choosing to continue usual business. Eventually the city was overwhelmed. Famine and revolt ensued. The army was sent in but too late; the plague had already spread through Provence despite the creation of physical travel barriers. The epidemic eventually faded but not before it had killed over one hundred thousand people in the province.

If this tale of plague ships and greed seems distant then it shouldn’t. Now, sailing ships become global air travel, markets proceed at the electric speeds of the internet, whispered conspiracies are passed on in virtual rooms rather than those of the tavern and gold crowns have become unfathomable fortunes. Distracted by the now-ness of our existence, we forget to look back. We have learned many things since then about our world, but not enough. The lure of the short term is still powerful.

These decisions we make are hard. From the beginning of this pandemic some have sought to represent this as a strange trolley problem, the philosophical dilemma whereby a person standing by a point-switching lever can divert a runaway tram from a track where five people are tied down, to a track where one person is. Leaving aside the political possibility that the person in control of the lever might not have any empathy for the people on either track, the problem here is also falsely binary, an “either-or” where an “and” would be truer. Pull a lever, it says, and choose between the economy for everyone and health for some. All the evidence currently globally points the other way – protect health and you are more likely to protect the economy. There is little evidence of a trade-off.

The decisions are hard, yet some would portray them as simple. Disbelieve them. A recent health policy paper in the Lancet, co-authored by Helen Clark, details the complexity of different strategies to ease Covid-19 restrictions into some approximation of regular life and the need to balance several societal concerns in a framework of responses. The fact that there is an array of measures implemented with different degrees of success in different contexts is enough to indicate that it is improbable that there exists an exact one size fits all answer or that one strategy will be continually applicable. The fact that experts may not agree or change their minds is not a sign that expertise is false, but that the only certainty about this future is that it is uncertain. Normal rules do not apply.

If it feels that New Zealand is now an island separated by a fragile border from a turbulent world, its waves still beating on our shores, then the history of pandemics has always been exactly that, successive grinding waves. The great plague pandemics troubled the world over many centuries and each single epidemic waxed and waned. Historically, heavy public health measures became more difficult to sustain through gathering clouds of misinformation, unrest and the influence of the anti-contagionists. We’re learning more as we progress through the waves, but progress will only be made by learning from where we have been.

In the longer term, the history of the plague began to intertwine with the revolutions of the Enlightenment that brought the ideals of individual liberty and free will. But now we may be reaching the point where prioritising individual freedom jeopardises collective survival.

We have always been capable of being short-sighted. It is no contradiction in terms to say that humans are capable of great acts of altruism yet also capable of catastrophically poor decisions borne out of greed and self-interest. It would be a lazy brushstroke to paint the Plague of Marseille as being just the result of one man’s momentary lapse of reason in sight of profit, but the truth is we have built many of our societies to prize that profit.

This goes beyond the pandemic to every current problem that we have created for our world by our presence in it. Perhaps the only true conspiracy theory is the one spread by a powerful minority, about a world that is much older than us yet exists only for us to accumulate wealth. The Grand Saint-Antoine lies as a warning at the bottom of the sea. If, for a few, self-interest fixes their gaze on the glittering prize on the horizon then we can choose whether we blindly follow them to that horizon or not. Because beyond it lies a precipice they would happily lead us over.

On spring days when the sky is deep blue it is difficult to envisage it turning the colour of the apocalypse, but in fact our year started that way. When fires burn, both literal and metaphorical, we feel driven to action but when they are burned out into ashes we turn away. As we cycle through the same loops though, we are getting closer to the point where no normal will exist again in any sense. So many fires have burned this year. Now the first gigafire, spanning more than one million acres, has burned in California. Whilst hope is still within our grasp, time is running out for us.

On one scale the coronavirus that plagues us is microscopic. On another we ourselves are made small. The rhythms of the Earth have a much longer wavelength than ours. In comparative timescales our whole existence, the mark we carve across the bright face of the world, is gone in an eye’s blink.

If anyone wishes to see what finally matters of their individualism, then I would invite them to walk along the black sands at the water’s edge of our West Coast, as the sun sinks into the western sea. Then come back the next day and find their footprints vanished. We are erased as individuals by the sheer scale of our world and its unrelenting entropy. Our collective hope of enduring, of thinking beyond plague, pestilence and fire, rests on two things: Our acceptance that we belong to the earth and not it to us. And our willingness to stand back, see things as they have been and simply ask, what if we did things differently? The lessons can be learned but they need to be learned now and not in a hundred years. Cut and untwist the Moebius strip you made. It becomes not a loop, but a path forwards.