The inclusive and intimate Thai martial art has forced one new follower to reckon with her inner agreeableness and fight the impulse to be nice.

Women have long been stereotyped as more apologetic than men. We are, apparently, more empathetic, caring, and better in tune with people’s emotions. The divisive YouTube celebrity and psychologist Jordan Peterson even goes so far as to suggest women’s “agreeableness” is a major contributing factor to the gender pay gap. Whether you side with Peterson or not, the fact remains that our culture continues to adhere to deeply entrenched ideas about how men and women are meant to behave.

Some might optimistically argue that recent years have brought about change. But progress is always slow, and long-held ideas and expectations – no matter how contested – are tough to resist.

So it is that despite my long-abiding fear of being described as “nice”, I also find myself falling prey to Peterson’s accusation of “agreeableness”, and, like many women, tend to apologise far too much (a stereotype that has some basis in fact, according to a 2010 study).

None of which I’d really thought much about until I put on my first pair of gloves at a Muay Thai gym.

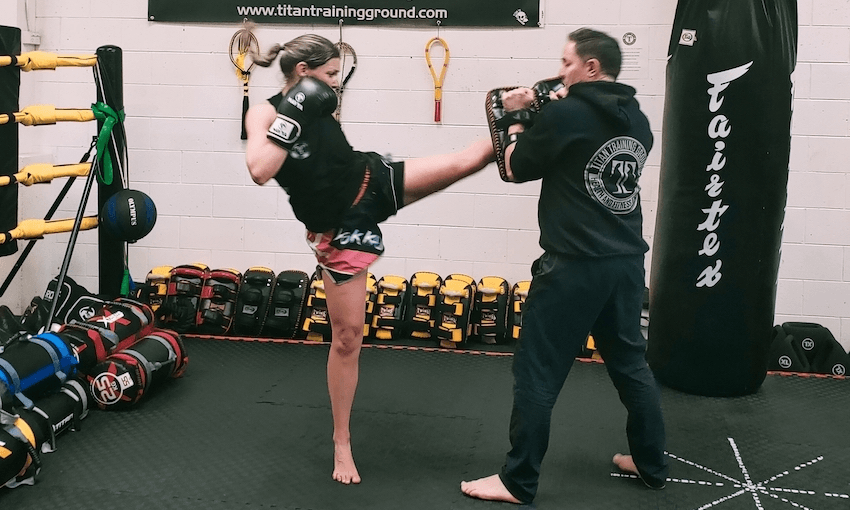

Often referred to as “the art of eight limbs”, Muay Thai (literally Thai boxing) is a stand-up martial art that uses eight points of contact – hands, elbows, knees, shins. Before this first class, my knowledge of Muay Thai was zero. Anything I did know about martial arts I’d gleaned from the Van Damme and Steven Seagal movies I’d watched as a kid. Women in those films tended to have big hair and bodysuits, their narrative purpose limited to a bedroom scene intended to secure our hero’s manliness while showing off his bulging biceps and oiled skin.

Little wonder, then, that despite being relatively fit, I was also extremely nervous. In fact, I probably would have canned it if I hadn’t promised a girlfriend I’d attend a trial class with her.

Somewhat surprisingly, I was almost immediately hooked. So much so that a fortnight later I’d cancelled my gym membership. As a workout, Muay Thai’s fairly versatile, offering a range of cardio and strength-based exercises that can be easily modified for different abilities or fitness levels (good news in the wake of the common Covid diet largely comprised of chips, chocolate and beer). However, it was the unexpected side effects I found most addictive.

Chief among these was an unravelling of a number of invisible gendered assumptions that I’d unknowingly found myself perpetuating. Despite a women’s studies undergrad degree and third wave embrace of gender performativity, the notion of actually hitting something remained utterly foreign to me. I hadn’t grown up rough-and-tumbling with boys and had always steered clear of physically aggressive sports (or any sports, for that matter). And so, the first time I landed a punch, I flinched, closed my eyes and instantly whipped out a “Sorry!”

The irony, of course, was that I was apologising for something I’d intentionally set out to do.

Undoing this impulse towards niceness and amenability has been a deliberate – and difficult – task. Mistakes are part of learning and, as such, don’t actually require an apology (a point that’s been enforced during training with threats of burpees for every sorry that slips out). More broadly, it’s meant a growing refusal to stop apologising for both my assertiveness and physicality in general, qualities we aren’t always comfortable seeing in women, even if we do valorise them in depictions of masculinity.

This perhaps goes some way towards explaining the historical lack of women in martial arts.

By all accounts, entering a martial arts training facility for the first time is terrifying for most people, men and women alike, triggering self-doubt and fears of being an imposter. On a personal level, this was worsened by my acute awareness of my gender. Consequently, as a new member, I tended to either run deliberately late or lurk around the edges trying to be as inconspicuous as possible. For a long time, I only trained in the quiet morning sessions, avoiding the much busier evening classes where the men’s physicality, their play-fighting and sheer size could feel overwhelming.

It’s important to point out that this isn’t a reflection on where I train or the members themselves, nor does it necessarily echo other women’s experiences. The owner has, in fact, worked hard to create an inclusive environment where diversity is welcomed. Kids are catered for, with options to train alongside their parents, and there’s a portacot and collection of toys on site. There’s even a jar of spare hair ties available (which shows a degree of thoughtfulness I’d never before encountered from a gym, including the women-only facility I’d attended where, really, you’d think they’d know better).

Instead, I suspect my apprehension was born out of a lifetime’s awareness of violence as inherently gendered.

Consider, for instance, the horrifying fact that one in three Kiwi women will experience physical or sexual violence at the hands of an intimate partner in their lifetime. Or that nine women will be killed by a partner or ex-partner every year. Our sexual assault statistics aren’t much better: only one out of every 10 attacks are even reported and, of those, only one will result in conviction. Not surprisingly then, the fear of violence permeates many women’s lives (a situation made doubly dangerous for some during the recent lockdown). It may even be a factor in why some women choose to learn a martial art in the first place. Auckland-based champion fighter Victoria Nansen, AKA Lady Smac, has spoken openly about her own childhood sexual abuse and the role martial arts played in helping her recover from it.

All of which is to say that while I definitely don’t subscribe to the “all men are rapists” branch of feminism, practising drills or sparring with guys can sometimes feel more loaded. At 56kg and 5 foot 3 inches, it can be fairly intimidating when a much bigger man tries to punch or kick me, especially after years of trying to avoid precisely that situation.

Fast forward one year, though, and much of my anxiety has eased. This is almost entirely down to the culture of respect and trust that’s been cultivated at Titan Training Ground, the Christchurch gym where I train. Finding a facility that’s built on these values is doubly important given how unexpectedly intimate Muay Thai turns out to be. A clinch, for instance, looks an awful lot like an embrace, while catching kicks or practising throws means handling another person’s (often sweaty) body and being prepared to be handled in return. This kind of physicality is markedly different from my past gym experiences. Here, rather than exercise being a way to achieve an idealised (read thin) female body, the body instead becomes a tool, the focus shifting from how it looks to what it does. Consequently, you’re much more likely to see the women in a Muay Thai gym comparing bruises than activewear.

You’ll probably still hear them apologising a lot, but you’re just as likely to hear someone encouraging them not to, a sentiment I’m now quick to share with other women starting out. This doesn’t mean we can’t offer an apology when it’s due – being held accountable is important and “sorry” can be a powerful word. Likewise, a rejection of agreeableness and the “tyranny of niceness” shouldn’t be mistaken for a lack of empathy or a refusal to try and bring generosity and warmth to our interactions with others.

Surprisingly, it’s these lessons that linger and which have kept me coming back. It’s just a shame they literally needed to be knocked into me.