Names are more than identifiers; they are complex links to heritage and identity.

There is a lot behind a name. Most of the time, the first thing we tell someone when we meet them is our name. It lets them know where we come from, what our background is and our whakapapa. Names can be used to immediately draw connections and link us to others. In te ao Māori, our whakapapa, the names of our ancestors, link us to the atua, our whenua, and our tribes.

Sometimes, people change their names. There are many reasons for this. For some, it can be simply because they like another name better. For others, it can be because of a marriage or divorce, a gender transition, a cultural or religious reason, to avoid confusion, or even professional reasons. Sometimes, it can be to avoid a negative past or reflect a new family dynamic, such as an adoption, or to honour a loved one.

Take for example Dominic Sinthupan, who is profiled in the new season of Takeout Kids. Dom’s mother legally changed his surname from his father’s to hers after being constantly asked to do so by the 13-year-old. While Dom’s reasoning for the name change was to have a surname that is easier to pronounce, it appears there is also a desire to no longer have the surname of his father, who was not a major part of Dom’s life growing up.

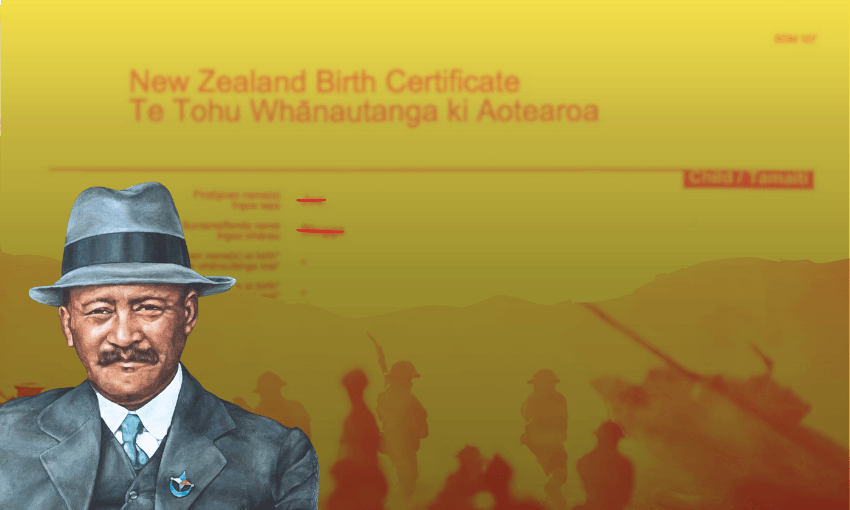

Legally, my name is Liam Ratana. I only started using a macron about five years ago, after meeting Donn Rātana, senior lecturer at the University of Waikato. Donn insisted I use a macron on the first a in his surname, which led to me doing some research and realising I should have been using a macron the whole time. Now, I want to change my surname entirely. Rātana isn’t my original whānau name. My paternal grandfather, Eruera Hapakuku, had attempted to enlist in the 28th Māori Battalion but was turned away due to being under age. Still keen to head to war and fight alongside his whānau, granddad later returned and enlisted under a different identity, Edward Rātana. His grandfather had earned the nickname Rātana due to being a staunch member of the Rātana Church, so he adopted that as his surname and it stuck.

Having the surname Rātana has led to me often being asked if I come from Taranaki or Manawatū-Whanganui, where Rātana Pā is. I always respond by telling people that I’m from the Far North and am not related to the founder of the Rātana Church, Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana. If I can be bothered, I will go on to explain the story of how my whānau came to have the name. While it’s a cool story to share and makes me proud of my great-great-grandfather’s commitment to the church and my grandfather’s bravery in joining the battalion, it can become a bit tiring at times. Besides, my actual surname has a lot of mana and some pretty powerful kōrero behind it too.

I remember attending a wānanga in 2005 at Te Hiku O Te Ika Marae in Te Hāpua, hosted by Ngāti Kurī. My father had begun researching our whakapapa and didn’t have much to go on, besides our original family name. One night, Dad stood up in the whare and asked if anyone knew about the name Hapakuku. An old lady at the back of the whare suddenly raised up and let out a surprised exclamation: ”Ooooh! That’s an old name, boy. I can’t tell you about it but I know someone that can,” she said.

That someone was Ross Gregory, a renowned kaumatua of Te Hiku o Te Ika and schooled by his elders in the teachings of Te Aupouri and Te Rarawa. It was through my father’s conversations with Ross that we learnt about the vast history associated with the name Hapakuku. It led to Dad learning more about our whakapapa and eventually lodging a claim with the Waitangi Tribunal alongside my uncle Mike Wikitera, seeking official acknowledgment of the mana of our people. If it wasn’t for knowing the Hapakuku name, we might not have ever rediscovered our whakapapa and our identity.

In his later years and as a result of his research into our whakapapa, my father began referring to himself as Hohepa Hapakuku. He would sometimes bring up the fact that he wished I had a Māori name, instead of the Pākehā one bestowed upon me by my mother. Dad wasn’t sure why she chose Liam but he thought it was purely because she liked the sound of it.

One of my cousins has legally reclaimed the Hapakuku surname and inspired me to follow in their lead. My son has Hapakuku as part of his surname and a Māori first name that describes his birth journey, as well as a middle name that honours his adoptive grandfather. For me, using the Hapakuku name is about reclaiming our identity, connecting us to our wider whānau and being proud of our rich whakapapa.

While I can be proud of my surname, despite it not being my original family name, some people are born with names that can serve as unwanted reminders of a hurtful past. Indigenous people around the world, even here in Aotearoa, have been given colonial names that their parents thought would make their lives easier. There are many examples of people with indigenous names struggling to get job interviews, their names being embarrassingly mispronounced, or being bastardised. While it was a consideration when naming my son, his mother and I decided that our boy deserved a name reflective of his cultural heritage and story, despite the perceived difficulties that come with having an indigenous name.

In Aotearoa, changing your or your child’s name is straightforward. Children under 18 need guardian consent, while those 18 or older can apply independently. The process involves completing a form, providing certified ID, signing a statutory declaration, and paying $170. Applications can be submitted by post or in person, and a new birth certificate can be ordered after the name change. For some, it’s a small price to pay.

The second season of Takeout Kids is out now, with new episodes released every Tuesday. Watch them all here. Takeout Kids is made with the support of NZ On Air.