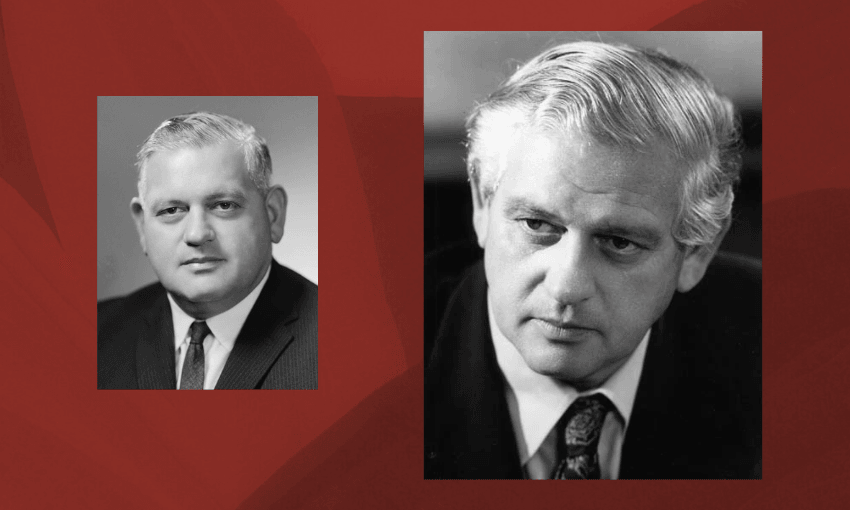

Fifty years ago today, prime minister Norman Kirk died unexpectedly. Anti-apartheid activist Trevor Richards considers his legacy.

The Spinoff Essay showcases the best essayists in Aotearoa, on topics big and small. Made possible by the generous support of our members.

Saturday, 31 August 1974. I had been out at a party in Wellington. Returning home, I switched on the radio to catch the midnight news. The lead item was one of those “where were you when…” moments. It was news that probably no one in the country was expecting: Norman Kirk, elected prime minister in the November 1972 Labour landslide, was dead. He was 51. He had been in power for less than two years.

In the days that followed, people flocked to parliament to pay their respects. More than 30,000 filed past his casket. Queen Elizabeth sent Prince Charles to New Zealand to represent her at the funeral. According to The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, the outpouring of grief was paralleled only by that which had followed the death of Labour’s first prime minister Michael Joseph Savage in 1940.

I remember the 1972 election campaign well. National had been in power since 1960. The line in Labour’s campaign, “It’s time for a change, it’s time for Labour,” captured the nation’s mood. Claire Robinson, a former communications professor at Massey University, has called “It’s Time” New Zealand’s best election slogan. Kirk dominated the 1972 campaign. It was a personal triumph.

Cinemas around the country screened Labour’s striking, full-colour, split-screen campaign advert. Kirk, against some initial personal opposition, had been persuaded to grow his hair a little longer for the campaign. Once a hulking 130 kilos, by 1972 he had slimmed down. His suits were fitted and stylish. Filmed racing up the steps of parliament, he looked dynamic; like a prime minister in waiting.

On election night 1972, my flatmates and I had celebrated Labour’s election victory with gusto. Twelve years of National party rule had finally come to an end. It was such a relief. The defeated National candidate for Papanui lived directly across the road from us. As the results of the election became clear, we blasted out ‘The Internationale’ and ‘The East is Red’ into the cool, late-night air. I did not believe Labour had all the answers to what was needed – at the time, I thought they had very few of the answers – but there was at last room for some hope.

Any assessment of Kirk’s premiership needs to begin with an appreciation of what New Zealand was like in 1972 and where it had just come from.

I was born in 1946, one of the baby boomer generation. The New Zealand of my childhood and early teenage years was largely rural, male-dominated and conservative. Men wore the pants; women an apron. Male hairstyles ranged all the way from short back and sides to bald. Liquor licensing laws required hotels to close their bars at 6pm.

Pākehā citizens – well, most of them – believed the country had the best race relations in the world. Prime minister Keith Holyoake had assured my Northland College school assembly that this was the case. Rugby was God, especially when played against South Africa. Since 1921, all-white South African rugby teams touring New Zealand had been welcomed by almost all Pākehā. The breadth of Māori opposition to such visits was never appreciated.

Frank Corner recalled, before leaving for New York in 1961 to take up the position of permanent representative to the United Nations, that the only piece of advice Holyoake had for him was to refrain from using the word “abhorrent” in relation to apartheid. “My people don’t like it”, Holyoake had said.

The nuclear issue wasn’t an issue. Nuclear power was favoured by both National and Labour. Abortion and male homosexuality were illegal. In Wellington, coffee bars were seen as hangouts for bohemians. In 1965, Christchurch musician Rod Derrett’s hit ‘Rugby, Racing and Beer’ summarised the culture of a generation.

By 1972, all this was changing. The newly elected third Labour government was facing a society in the midst of transition. The policies and values of post-second world war society were being vigorously challenged, in particular by baby boomers. The issues of concern were many: New Zealand’s involvement in the Vietnam war, French nuclear testing in the Pacific, the scheduled 1973 Springbok tour, and the presence of US military bases at Washdyke and Mt John. There was a range of issues affecting women’s rights, especially the demand for access to safe and legal abortions. Issues affecting Māori were being vigorously promoted: land loss, te reo and the role of the treaty. A Māori renaissance was underway. Environmental issues also figured in this complex mix.

Labour had come to power in the midst of a developing battle over what sort of country we were going to be. The question was, whose side would Labour be on? For those demanding change, would the new Labour government be a help or a hindrance?

By the time the fourth Labour government left office in 1990, the New Zealand of my childhood was a distant memory. Māori were recognised as tangata whenua. We were proudly anti-nuclear and anti-apartheid. Laws against male homosexuality had been repealed. Abortion access was being liberalised. Coffee became a huge part of daily life. (Wellington today has more cafes per capita than New York City.) The monoculture of rugby, racing and beer was well and truly dead.

This change did not occur overnight. It began in the second half of the 1960s, although the engine-room for much of the change was located in the 1970s. It was driven by ordinary New Zealanders who saw the need for change, who gave their energy and time to a wide variety of causes, who put their bodies on the line. It was an energy political parties and parliament were able to tap into.

Change often seemed slow in coming. It was a long and gradual process, but it had to start somewhere, and it started to gather real momentum after the election of the third Labour government in 1972. The person driving much of that change, especially in the international sphere, was Norman Kirk.

Although his tenure in office was brief, his accomplishments were greater than those of many of his predecessors whose time in office had been significantly longer. This was partly a consequence of the timing of his premiership. By the time he was elected, the force for social change was already robust and multifaceted. Kirk’s developing sense of both New Zealand’s place in the world, and the type of society we should strive to be back home, were broadly in step with many (but not all) of those winds of change.

From the outset, Kirk presented the image of a man in a hurry. Within a month of assuming the treasury benches, New Zealand had established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. During the election campaign, he had promised that New Zealand’s military withdrawal from Vietnam would be completed by Christmas. It was. Before the year had come to an end, compulsory military training had been ended. In the months that followed, a grant was made to the United Nations Trust Fund for South Africa, a scheduled all-white South African rugby tour of New Zealand was cancelled, and our navy had become involved in protests against French nuclear testing in the Pacific.

At the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Ottawa in 1973, Kirk established warm personal relationships with the leaders of a number of Commonwealth countries, particularly Indira Gandhi (India), Julius Nyerere (Tanzania) and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (Bangladesh). Kirk invited Julius Nyerere to visit New Zealand, and in 1974 he became the first African head of state to set foot on New Zealand soil.

Kirk could be openly critical of the United States. In early September 1973, the democratically elected Chilean government of Salvador Allende was overthrown in a bloody coup. Kirk knew Allende and regarded him as a friend. Two weeks after the coup, Kirk addressed the United Nations General Assembly in New York. He was openly critical of the direct role the US had played in the coup. The following day he met with president Nixon at the White House.

Kirk was heading an activist government unlike any seen in the previous 40 years.

Kirk said he wanted New Zealand’s foreign policy “to express New Zealand’s national ideals as well as to reflect our national interests”. This notion was behind two of the Kirk government’s most significant actions: opposition to French nuclear testing in the Pacific, and the cancellation of the 1973 South African rugby tour.

When France first began atmospheric nuclear testing in French Polynesia in the mid-1960s, official New Zealand protests followed. With the 1972 election of Labour governments in both New Zealand and Australia, official opposition to these tests became more strident. In May 1973, in an effort to have these tests banned, both governments took France to the International Court of Justice. The court issued an interim ruling calling for the tests to cease. France ignored the ruling.

In June 1973, New Zealand opposition to French nuclear testing went beyond words and legal challenges. Two navy frigates, HMNZS Otago and HMNZS Canterbury, sailed into the test area. Kirk told the 242 crew of the Otago that their Mururoa mission was an “honourable” one − they were to be “silent witness[es] with the power to bring alive the conscience of the world”.

To emphasise the strength of New Zealand’s opposition to these tests, on board the Otago was cabinet minister Fraser Coleman. Explaining Coleman’s selection, Kirk said that the names of all 23 cabinet ministers had gone into a hat, and Fraser Colman’s, the lowly ranked minister of immigration and mines, was drawn out. Some insiders unkindly suggested that yes, there were 23 slips of paper in the hat, but they all had Fraser Coleman’s name written on them.

The opposition National party declined Kirk’s invitation to send a representative on the protest voyage. National’s leader, Jack Marshall, saw the despatch of the frigate as a “futile and empty gesture” that would only inflame the situation.

These protests grabbed world attention. They didn’t result in an immediate end to French nuclear testing in the Pacific – that was only achieved in 1996 – but they were influential in France’s 1974 decision to conduct its tests underground.

Kirk’s determination to change the way New Zealand viewed itself, the way it presented itself to the world, had first been on display a couple of months earlier. On 10 April 1973, his announcement that the government would not allow a Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand to take place was probably the first major marker of a seismic shift.

It is doubtful that any single issue was more central to New Zealand’s changing political and social landscape than that of our rugby relationship with apartheid South Africa. No issue better encapsulated the differences between those in New Zealand seeking change and those committed to maintaining the status quo. It was a lightning rod for conflict.

Frank Corner, secretary of foreign affairs during Kirk’s prime ministership, told me in an interview in 1998 that Kirk “could see that if he stopped the tour, he could lose the next election. But the tour did not fit in with his view of what New Zealand should do in the world, and what its standing would be should it proceed.”

It was a brave decision to stop the tour, and it engendered strong opposition, much of it absurd. Jock Wells, the president of the Wellington Rugby Football Union, called the tour’s cancellation “the worst news I have heard since 34 years ago when Chamberlain stated that England was at war with Germany.”

The decision to stop the tour had a remarkable but little-known impact on one of South Africa’s most important anti-apartheid activists. In 1995, Nelson Mandela told Norman Kirk’s son Phillip that learning of the tour’s 1973 cancellation from his prison cell was the first time he thought apartheid might actually be able to be ended in his lifetime.

The extent to which it was Kirk who drove the decision to stop the tour became clear the year following its cancellation. In 1974, former Auckland University Students’ Association president Bill Rudman was teaching at the University of Dar es Salaam. That year’s Commonwealth finance ministers meeting was being held in the Tanzanian capital. Rudman was one of the New Zealand expats invited to meet with finance minister Bill Rowling. Rudman, who had been one of the 14 who had attended the inaugural meeting of the Halt All Racist Tours (HART) movement, congratulated Rowling on the government’s decision to stop the Springbok tour. Rowling’s response took Rudman by surprise: “That was Mr Kirk’s decision.”

Kirk’s understanding of his foreign affairs brief was detailed. In the early 1970s, the politics of South Africa’s liberation struggle were complicated. Meeting with Kirk in early 1974, I was part of a small National Anti-Apartheid delegation discussing recent developments there. We left impressed. Kirk opened the conversation, and after five minutes, we realised there really wasn’t any need for us to be meeting with him. The position he was advocating was much stronger and more detailed than anything we had gone seeking to achieve.

Kirk was fortunate to have Frank Corner at the head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He was both vastly experienced and on the same internationalist wavelength as Kirk.

Not all senior civil servants were an asset. Kirk was badly let down by the leadership of the Security Intelligence Service. Shortly after the cancellation of the 1973 rugby tour, HART became aware that the previous National government had given the SIS approval to bug HART’s headquarters in Christchurch. An agent had been installed in the house next door. Electronic equipment enabled conversations to be picked up and recorded. One of my flatmates, HART activist Piers MacLaren, wrote a detailed letter to the prime minister advising him of this.

Kirk’s response was unambiguous. “The Security Service considers that your allegations are unfounded and possibly libellous. In my turn, I can assure you that fears on your part that your name or the names of your flatmates are on Security Intelligence files are groundless.” Kirk had underlined the words “are groundless” with his fountain pen.

The prime minister was shortly to receive a shock. In her book Diary of the Kirk Years, Kirk’s private secretary Margaret Hayward writes, “Brigadier Gilbert [NZSIS director] is overseas and Mr Maling, the deputy director, has called to see the boss. The SIS is in trouble. Mr K told me Maling said they had been bugging Trevor Richards at HART headquarters … Mr K was furious. The SIS had assured him they were doing no bugging at all. When HART had written to him, Mr K had referred the letter to the SIS which stated the allegations were unfounded. What the hell were they doing making a liar out of the Prime Minister?” A memorable phrase from Kirk followed: “As things stood, it was like riding a bicycle downhill with no brakes”.

The matter surfaced again in 1974, a few months before Kirk’s death. By then my relationship with Kirk was good. At the end of a meeting at which a small group of anti-apartheid activists had been discussing the liberation struggle in South Africa, the prime minister followed us to the corridor and called me back into the office. It was the first time I had seen him looking tentative, uncertain. “How is our mutual friend?”, he asked a little awkwardly. I had no idea what he was talking about. “Has he been causing you more trouble?” I knew I was not going to be able to unscramble this one. “I’m sorry prime minister,” I replied, “I’m not sure what you are referring to.” He smiled and said, “Brigadier Gilbert”.

I told him that I was not aware of any trouble, but that I had not of course been aware of the previous bugging until after the event. We stood for a few minutes and chatted. The prime minister made it clear that he was very concerned about what had happened and that he was going to “sort the SIS out”. I left believing him.

Domestically, especially on matters relating to race relations, there had been significant progress since the change in government. In 1973, the Labour government announced that from 1974, Waitangi Day would be a national holiday known as New Zealand Day. With the exception of the 1940 centennial celebrations, Waitangi Day had barely registered with most New Zealanders. A public holiday only in Northland, it was regarded as no more than a local event. Kirk sought to change that; to make the day a celebration of New Zealand’s multiculturalism. A photograph of him walking hand-in-hand across the marae at Waitangi with a young Māori boy remains one of the enduring images of his leadership.

Labour’s record on race was not, however, without serious blemish. Relations with the Pasifika community were badly damaged when dawn raids were instituted against alleged overstayers from Pacific Island nations. Dr Melani Anae, a foundation member of the Polynesian Panthers (an activist group opposing the Dawn Raids) and later an associate professor in Pacific Studies at Auckland University, described these raids as “the most blatantly racist attack on Pacific peoples … in New Zealand’s history”.

Kirk had less success dealing with domestic economic issues. This is unsurprising. Small states have a limited capacity to overcome unfavourable international economic headwinds, and Labour was to encounter these. But not immediately. One of his first actions was to give pensioners a Christmas bonus. Labour’s first prime minister, Michael Joseph Savage, had done the same in 1935. In Kirk’s first year, the country’s books enjoyed a record surplus. The currency was revalued. External factors, however, were about to plunge the New Zealand economy towards recession.

The slowing world economy and an unprecedented rise in oil prices (“the first oil shock”) led to a rapid increase in government expenditure and spiralling inflation. By early 1974, the country’s economy was suffering. Kirk remained determined, no matter what the state of the economy, to implement election promises. To do otherwise he regarded as a breach of faith. His economic views remained firmly rooted in social democrat orthodoxy. He believed that “the role of the welfare state is to set people free”. The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography called Kirk “Labour’s last passionate believer in big government.” In the midst of a serious economic downturn, he died.

On issues such as abortion law reform and gay rights, Kirk was a social conservative, opposed to any change to the status quo.

Over the period of his premiership, I had the opportunity to observe at close quarters, on the anti-apartheid issue, Kirk in action. My opinion of him was to change significantly.

At the time that Kirk became prime minister, there was little indication that he would be remembered as a great internationalist. I had been enthusiastic about the Labour campaign advert I had seen in cinemas – I wanted Labour to win the election – but on the issue that concerned me the most, my view of Kirk was decidedly unenthusiastic.

During the 1972 election campaign, his views on the scheduled 1973 rugby tour had inspired no confidence in me. National had prominently displayed full-page newspaper advertisements promising that it would not be blackmailed into stopping the rugby tour. Labour, on the other hand, had assiduously sought to avoid the issue. In the run-up to the election, Labour promised not to interfere with the tour.

Once in power, Kirk seemed to be holding true to Labour’s election promise. He clearly had concerns about the tour, but there was nothing publicly to indicate that he was going to move in to stop it. Concerned by this apparent lack of commitment, in early February 1973 I issued a press release outlining what HART would do if the tour proceeded. My statement suffered no ambiguity. It received wide attention. The prime minister’s response was immediate and sharp: “Richards, you are not running the country.”

I had always thought that Kirk and I had little in common. He was someone for whom 1960s counterculture had completely passed by. I had hair that my girlfriend’s mother said resembled a coprosma bush in a southerly. We were an unlikely pair to hit it off.

It was a difficult time for both the government and the anti-apartheid movement. We doubted the government’s commitment to stopping the tour, and Kirk – who, unknown to us, was becoming increasingly of the view that the tour should not proceed – was concerned that further statements from HART similar to that of early February would make his task more difficult. Kirk’s solution was to establish back-channel communications between himself and HART.

Following my February 1973 statement, the message Kirk initially wanted relayed to HART was that the job of the anti-apartheid movement was to be calm and quiet. The government believed that our views were well-known, and the ball game was now being played on a different field – theirs. As time went on, although there was little public evidence to suggest it, we were being told to relax – the prime minister had the matter in hand.

Sometimes things dropped off the back of a truck. A few weeks before the tour’s cancellation, the prime minister met with a deputation from the pro-tour lobby. Some time later, a full transcript of the meeting found its way into HART’s hands. Clearly the government had wanted us to see it. The prime minister had told the delegation that his decision on the tour must be based only on one fact and that was what is in the best interests of New Zealand. Here was a PM thinking about who we were, New Zealand’s place in the world. “There is no evidence that I can find,” he told the delegation, “that supports in any way the continuation of the tour.”

In the period following the rugby tour’s cancellation, my relationship with Kirk changed. I settled into a comfortable, cooperative relationship with the prime minister. When he stopped the 1973 tour, Kirk said that “today’s announcement has been the establishment of a principle”.

For the remainder of the government’s term in office, many sports bodies sought to ignore this principle. A number of New Zealand sporting bodies, most notably rugby clubs and the Lawn Tennis Federation, remained intent on either issuing invitations to, or accepting invitations from, whites-only sports bodies in South Africa to tour. HART became energetic little bureaucrats, providing a receptive government with the information they needed to dismantle the often duplicitous claims advanced by sports bodies justifying these tours.

On other issues, Kirk’s relationship with HART was also warm. In the period after the tour was cancelled, the government and HART both developed warm relations with the Tanzanian government: Kirk with Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere, myself with Tony Nyakyi, head of the Tanzanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

One day in June 1974, the phone rang. It was the prime minister. I was about to travel to Tanzania as a guest of government to take part in celebrations marking the 20th anniversary of the formation of the party that had led Tanzania to independence. The government had also been invited, but the New Zealand Foreign Ministry had failed to alert Kirk to this. He was furious. Would I please explain to Nyakyi and others why there would be no official New Zealand representation at the celebrations? It was all a far cry from “Richards, you’re not running the country.”

More than any other administration since the 1950s, the third Labour government pursued policies which laid the foundation for New Zealand’s shift into a more progressive social and political space. Specifically, it changed how New Zealand related to the world; how it thought of itself. Within that government, no one was more instrumental in that process than prime minister Norman Kirk. Together with Peter Fraser, he was one of New Zealand’s two great 20th century internationalists.