Today marks 75 years since the first official refugees – Polish children fleeing the horrors of World War II – arrived in New Zealand. On the anniversary, historian Ann Beaglehole reflects on our history of settling refugees.

Hundreds of smiling school children, waving New Zealand and Polish flags, greeted the Polish children when they arrived in Wellington on 31 October 1944. It was a big day for Wellingtonians – the weather had put on a great show and the excitement of the arrival of the ship could be felt throughout the capital city.

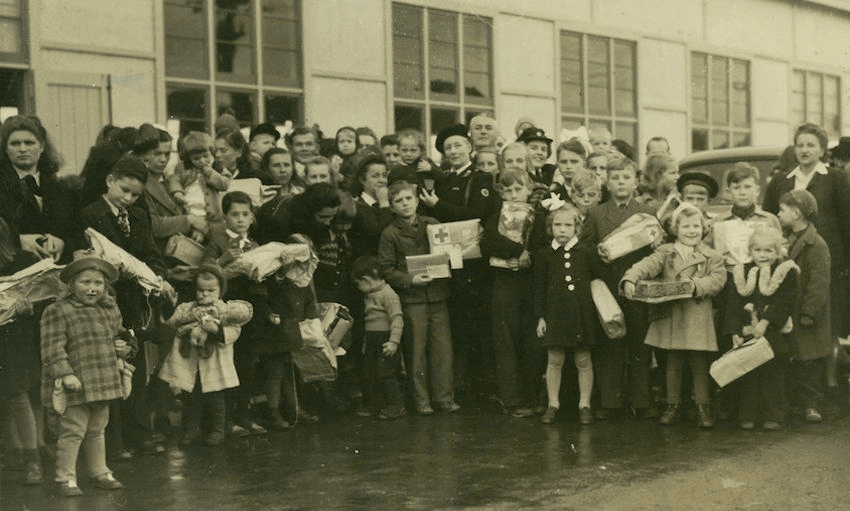

Wellington offered a warm welcome to the 733 Polish children and the 102 caregivers travelling with them. One of the children, Jan Wojciechowski, recalled that when he climbed up into the train which would take them to the children’s camp at Pahiatua, he was handed a bottle of milk, a carton of ice cream and a boxed lunch, prepared by New Zealand Red Cross.

Among the victims of World War II were thousands of Polish children uprooted from their homes, who had lost one or both parents, and who had known years of war, hunger, prison camp life and disease. The Polish children who came to New Zealand in 1944 were the first refugees to be distinguished from other migrants in New Zealand’s official statistics. The country’s formal refugee resettlement programme is usually considered to have begun with their arrival. The children came to spend the duration of the war in New Zealand but, owing to the political situation in Poland after the war, they were accepted for permanent settlement rather than returning to Europe as originally planned.

The idea of giving asylum to as many of the Polish children as possible came from Countess Wodzicka, the Polish Red Cross delegate in New Zealand, and wife of Poland’s Honorary Consul Count Kazimierz Wodzicki. She suggested it to her friend Janet Fraser, the wife of then Labour Prime Minister Peter Fraser.

It has now been 75 years since the Polish children found safety in New Zealand – 75 years of what we now call ‘refugee resettlement’ in New Zealand. It is important to note that there were refugees in New Zealand before 1944, though not categorised as such.

Since 1944, New Zealand has accepted more than 35,000 refugees. Although the number is not large relative to the many millions of refugees and displaced people in the world, it is significant for a country of this size.

One of New Zealand’s outstanding achievements over the 75 years has been in enabling volunteers in communities to be involved in resettling refugees. In the 1970s, New Zealand relied on the Interchurch Commission on Immigration and Refugee Resettlement (ICCI), which later re-formed as the Refugee and Migrant Service (RMS), to harness volunteers as sponsors. The volunteers, many from religious organisations, had a vital role in helping refugees, particularly with their housing, language and employment needs. At its best, sponsorship led to the formation of life-long friendships between sponsors and newcomers.

In 2012, New Zealand Red Cross became the lead agency responsible for settling quota refugees and for harnessing community volunteers. New Zealand Red Cross, well-known for its strong presence in communities and thousands of volunteers, supports former refugees to rebuild their lives in Aotearoa.

It is remarkable how many New Zealanders, located far away from the world’s conflict zones, have wanted to be involved with helping refugees. Acting as individuals, or within community groups, they have devoted themselves to the rescue of victims of violence and persecution in distant places. They have believed they lived in a lucky country and therefore should take some responsibility for the less fortunate in the world.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, New Zealand led the world in the acceptance of refugee families then considered by other countries as ‘hard to settle’ (usually because the ‘bread winner’ was over 45 years old, or a member of the family had a disability of some kind).

In 1973 Labour Prime Minister Norman Kirk told UNHCR (the UN Agency for Refugees) that his Cabinet would be sympathetic to welcoming more refugees who were considered harder to settle, for he would not like New Zealand to be a country which did not take its fair share of such international responsibilities. New Zealand remains one of the few countries in the world today which welcomes refugees with disabilities or needing medical attention.

Seventy-five years on, we celebrate New Zealand’s achievements in welcoming refugees and saving the lives of thousands of people. However, the country’s past policies were restrictive; discrimination on the basis of ethnicity and religion characterised New Zealand’s immigration and refugee policy until the late 1980s. Chinese, Jews and Muslims were among the targets for rejection. Under the 1931 Immigration Restriction Amendment Act, Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis were denied entry; those asking about entry were told it was hardly worth them applying because non-Jewish applicants were regarded as more suitable type of immigrant.

A major shift in policy in 1987 ended selection based overtly on ethnicity and religion. New Zealand’s annual refugee quota was established then, set at 800 refugees. It formalised New Zealand’s commitment to settling refugees, replacing the earlier piecemeal approach of individual quotas. In 1997 the quota was reduced to 750 annually and the government agreed to pay the travel costs of refugees. The Labour-led government increased the quota to 1000 in July 2018.

By the early 1990s, the process for setting the annual quota involved: first an approach to New Zealand from UNHCR to accept refugees in greatest need of resettlement; after which New Zealand officials selected refugees with emphasis on the humanitarian aspects of each case. Since 2012, New Zealand has focused on resettling refugees in the Asia-Pacific region. In October 2019, the Government announced that the much-criticised family links policy, which had impacted the selection for the quota of refugees from the Middle East and Africa since 2009, would be stopped.

Refugee policy has close links to immigration policy and to foreign relations. New Zealand’s changing response to pressures from Britain, USA and UNHCR has had major impact on resettlement. The country’s resettlement story over 75 years must also be seen in the context of massive changes in New Zealand over that time, not least becoming a more culturally diverse society through international migration. Former refugees in New Zealand used to be predominantly from Europe. This changed over the years since 1944 to refugees coming mainly from Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America.

Looking back at New Zealand’s unique approach to refugee resettlement over 75 years sheds light on present refugee resettlement issues. One of these is ensuring refugees come to a welcoming community. Most New Zealanders have so far resisted populist and exclusionary ideologies, with their focus on ‘alien’ outsiders, prevalent in many places overseas. At a time when we have recently experienced the worst terror attack in our history, with the shooter’s victims including refugees, there are challenges ahead. But there is every reason to suppose they will be overcome.

Ann Beaglehole is the author of ‘Refuge New Zealand: A Nation’s Response to Refugees and Asylum Seekers’ (Otago University Press). She came to New Zealand as a refugee from Hungary in 1957. This piece was commissioned by the New Zealand Red Cross.