Perhaps those entrenched with a superior view of their place in the world may describe Dad as ‘reasonable’. One wonders if that same bar exists for non-Māori.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand

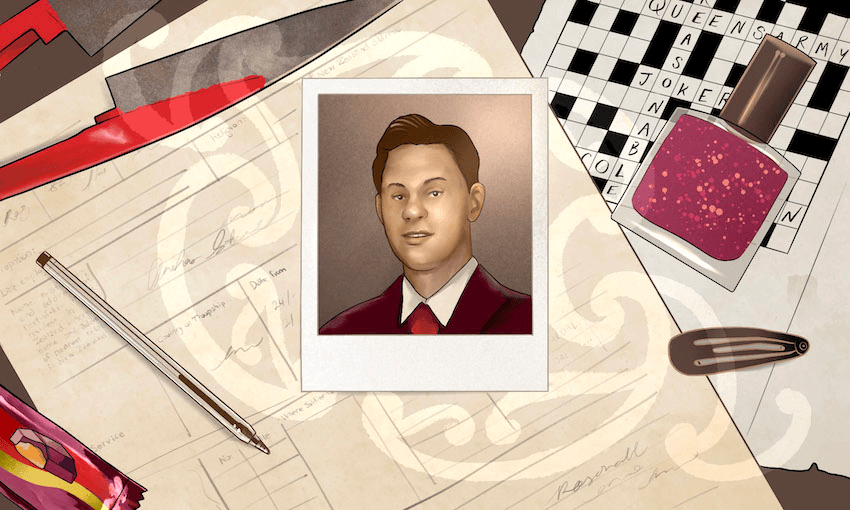

Original illustration by Isobel Joy Te Aho-White

My dad died last year. We were blessed in that he passed at home with his whānau by his side on his last journey. It happened while there were Covid-19 restrictions in place but thankfully he wasn’t in a hospital where staff, albeit beautiful and caring, were the last faces he saw. He also surpassed eight decades of life which, for a Māori man, is bucking the statistics.

A couple of months before his passing, we received his official army papers. Dad had never talked up his army contribution, though we did discover he’d been part of the Queen’s guard on one of her visits. The day the papers came, Dad was in hospital. In reading the sender’s details (NZ Defence Force), Mum decided to come to my home to look at them together. We excitedly opened the envelope. After the obligatory name, age and address came a requirement to be a “British subject”. This heralded the next “overview section” and was perhaps a clue to stop reading. But we didn’t.

Cursive handwriting in the overview section described my precious dad as of “medium physique, speech good, manner fair – a reasonable type Maori (sic).” I looked incredulously at my mum and inquired: what is a “reasonable type Māori?” She only shook her head. I had a bunch of fleeting thoughts. Perhaps bizarrely, it reminded me of my days on a farm when you would haul the ewes over the board and decide whether to cull them. They were either “reasonable” with good teeth, physique etc, or not.

Dad was my superhero. One day, he saved my life when the car door came open while driving on the open road. Long before car seats were ever thought of, let alone made, he somehow managed to reach into the back seat and pull me back into the car. I vividly remember the tarseal coming closer and closer while he managed to manoeuvre the car.

One of my earliest recollections of life was Dad waking me one night and bringing me a little black and white kitten in his lunchbox. He loved all animals, and animals loved him. He had rescued the kitten from the perils of those who did not feel the same way about animals. Panda became my loved friend.

Dad was of the generation of Māori boys sent to do trade training. His real love was shearing, but he dutifully went off and earned his ticket as a builder. He built many things, including a road bridge which stands today, a community hall and a split-level home for our whānau, which we thought immensely flash at the time.

He was also the generation of Māori beaten for speaking the only language they knew. As a young boy, he lived with his deeply treasured Nanny at the marae, and this was the happiest time of his childhood. He grieved losing that ability to speak Māori fluently throughout his life. Ironically though, there were times when, after operations requiring a general anaesthetic, he would recite ancient tauparapara that he learnt in wānanga with his Koro. I know this because there were two occasions that a nurse in post-op came to get me because staff thought he was having some sort of psychotic reaction. Nope, deep in his cells somewhere, that ability had not been entirely lost, despite his assertion otherwise when fully conscious.

He didn’t lose the ability to sing waiata. We never had radios in cars nor needed one. Dad would sing from the moment the engine turned over until it stopped, tapping on the steering wheel as we went. He was one of those musicians that could play by ear. A trait that has well and truly missed me. His arrival home from work was often announced by the tune of ‘Remembrance’ being played on the old piano we had in the garage. I loved to watch him play. His fingers would dance gently over the keys so naturally and easily.

He was also naturally gifted on the sports field, with coordination and athleticism that many dream of and have to work so hard to attain mechanically. I was one of the latter, but Dad would spend hours with me outside, passing balls and helping me to jump higher with each pass. When I made representative teams in Wellington, he would drive nine hours round trip just to watch me practise at the cold and windy Hataitai netball courts. I would feel so bad for him that I sometimes bought him Caramello chocolate bars (his favourite) to eat while standing in the cold. He never saw it as a chore, only a privilege.

When my children were born, I would look out for his car to come up the farm driveway every day. Then I could run around in a frenzy doing farm chores and household chores while my children were sung to, read to and cuddled. He made all the difference in my life during those times, and I don’t think I ever thanked him. Again, he saw it as his privilege.

I don’t assert that Dad was a perfect human. Perhaps he could be described as a man’s man in his younger life – playing rugby, drinking beer, playing pool for money. Yet this same man would sit patiently while the girl mokopuna would put hair clips in his hair and giggle profusely while painting his toenails. He had patience and tolerance in spades. He was the parent that taught you to drive because even if he was in danger of being catapulted through the windscreen, he would calmly sit there and say, “shall we try that again, Bubs?.

He loved people. He loved talking to people. He was genuinely interested in them and their lives. He saw richness everywhere. When he passed, my mum had a visit from the ambulance driver who had once taken him to hospital. She detailed how she had written in her logbook, “BEST DAY EVER – got to transport Peter Te Karu – what a lovely man.” I don’t think I was ever more proud of Dad than when he was in the intensive care unit and feeling so unwell. He was only ever demonstratively grateful to all the staff. They regularly commented on how they wished everyone behaved with such grace and gratitude.

He was well-read on all subjects, and people always commented on his oratory skills if he stood to speak somewhere. He had a wide vocabulary and did crosswords with speed and ease, but his ability to connect with people in a room made the difference.

Some people may not recognise the stance of superiority in the overview section of the army papers. Some people may not comprehend that a belief of superiority based on race is, by definition, racism. Those people are more likely to perpetuate the racism that sadly pervades today. It may have been more overt when Dad was a young man and was prevented from playing tennis at a City Tennis Club. Regardless of his claim that he and his mate from Tūhoe rohe were the best players in the city, they were unable to demonstrate this. It was also overt when I was growing up and the motel would suddenly become non-vacant if Dad asked for a room, despite a sign outside displaying otherwise. It was more casual in approach in his later life, but nonetheless, just as cutting.

When he turned 80, I took Dad to Te Waipounamu for a holiday. We drove to Kaikoura and ordered fish’n’chips. He chatted all the way about wool sheds where he’d shorn sheep and the “jokers” (men) he had met. He questioned how he could detail the Anglo-Saxon Battle of Hastings, England, in 1066 but nothing in-depth on the history of the South Island. And how he only knew about Parihaka because my Koro (his dad) had lived there for a time milking cows, not because he was taught it in school.

The wheels of colonisation continue to play out in contemporary society, and we are all disadvantaged by them. Those that are directly affected – losing land, language, culture, history – are compounded by these systemic losses. Even those that have benefited from the supplanting are still losers in some respects. They also miss out on a rich tapestry, Indigenous history, and ways of knowing. Increasingly and ironically, the world is only just looking to Indigenous knowledge for solutions to things like climate change and systems infrastructure when it has been around in some cases for millennia.

In Dad’s final hours, it was this belief that helped us all. He distinctly saw his treasured Nanny and he whispered to me, “Nanny is here now, Bubs.”

Sadly not all his mokopuna could be with us while we kept him at home in the black suit he had requested and his rugby socks. My daughter wrote an incredibly beautiful letter to her Koro which she popped in his suit jacket along with a shearing comb her partner lovingly sharpened. My tall, strong son wept openly. My beautiful cousins arrived at our home and guided their Uncle on the very final stage of his journey with his Nanny (their Kuia) and other ancestors.

Perhaps those entrenched with a superior view of their place in the world may describe Dad as “reasonable”. One wonders if that same bar exists for non-Māori. I assert that Dad was not only reasonable but a great father and a wonderful man. The measures of greatness or success are often defined through the lens of power, wealth and title. Society even celebrates wealth by publishing lists ignoring the compounding sociohistoric injustice that pervades for “reasonable” Indigenous people. The markers noted by the army as making my father reasonable show the complete dismissal of attributes that define the great man I knew.

If we conscientise ourselves to racism and superiority views, we would be far richer as a nation and rewarded in seeing the fullness of people. In the words of Bishop Desmond Tutu, “if you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” We must call out racism in its many shapes and guises. People with advantage and power have arguably more leverage to do so. To accept the world as it is is something none of us should stand for.

We didn’t show Dad his army papers.