I’m scared to see a dead body, I’m too young for this, I should have applied at Maccas.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

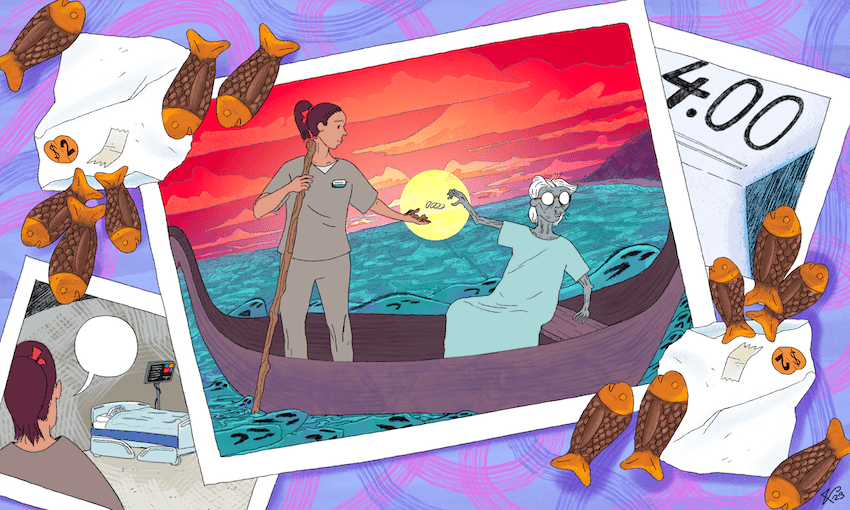

Illustrations by Sean Lewis.

My first corpse was on a soft and honeysuckle Tuesday, a lovely afternoon to die. I did it for four bucks.

I don’t know who she was. I know her name, which I read on her bracelet, to make sure I had the right woman. I know the heft of her flesh, solid and still warm, and the meaning of the old adage “dead weight” as I cradled her from bed to gurney. I don’t know her face, only a shade of it: liver-spotted, waxen, the sallowness of an old pillowcase, mouth sloped in a slack oblong, before I zip her up. She’s then fettered beneath a woolly, dark-green shroud, the material suspended by poles to create a vague ambiguous silhouette.

I’m a gauzy 17-year-old schoolgirl with a ribbon in my hair and nobody suspects a thing. Mavis and I trundle through fluorescent-buzz corridors and smile at pregnant parents with their babies, like I’m pushing a supermarket trolley instead of a woman uninhabited. If the shroud wasn’t velcroed in place it’d fly off, and that wouldn’t be a very optimistic sight for everybody else at the hospital. Mavis is very good and doesn’t make a peep.

There’s one giveaway, which is when we board the elevators. We conspicuously avoid the lift on the far left, where the kitchen ladies load pottles of jelly and smuggle muffins into my scrub pockets. Our tūpāpaku is still our patient, still retains her mana and tapu, and we keep the food away from her, rāhui imposed. I press -1 and wonder if there are one or two people in the lift right now.

“Patient to Ward 13,” my manager John had sputtered in my phone. “Get in quick if you want a bonus.”

I will tell you a secret. There is no Ward 13 at North Shore Hospital, officially.

I am young, curious, pretentious, and I remember the word triskaidekaphobia, and I laugh, because the hospital skips straight from 12 (General Medical) to 14 (Older Adult Health Services), the way a kid skips over cracks in the pavement. I am not a kid; I am 17 and eternal and know big words, and I’m so brave but oh but in my gut I’m scared to see a dead body, I’m too young for this, I should have applied at Maccas.

My job title is “orderly”. We do fetch quests, mostly. We move patients, documents, and wobbly bags of lukewarm bodily fluids from one end of the hospital to the other. It’s my first ever job and I love it to bits. I love feeling like I’m helping people, I love the ever-changing tasks, I love the adult feeling of drinking coffee and receiving my minimum-wage paycheck ($16 per hour). I enjoy befriending patients and hospital staff, the latter being nerds who are very eager to share their work with me.

One radiologist invites me to watch a woman being zapped in an MRI machine. I watch her consciousness light up on a screen as the doctor gleefully points out each brain tumour. A haemotologist, who I frequently visit with sacks of blood in tow, asks what my blood type is. I don’t know, I say, and she asks if I’d like to find out. She pricks my skin with a needle, pops my blood into a centrifuge, and the next time I see her, I learn that I’m something boring like A-.

The job description mentioned “body dispatch”, a clinical way of asking if I’m comfortable handling dead people. In my youthful naivety, I don’t know if I actually expected to be assigned this work, let alone whether or not I am comfortable doing so. When John gives me my first body dispatch, I dutifully accept and trot over to collect Mavis.

Everything changes here, I think, as I open the door.

You enter the room and open your mouth to say hello, then don’t, then almost say hello anyway, because it seems silly but strangely rude not to.

She is lying still and holy and anticlimactic. There’s no presence, or lack of presence, or explosive, watershed, divided before-and-after; something obvious to cultures not my own, ones where bodies are treated with friendship and company; dead in the living room to be sung and laughed with. Tuesday’s child is full of grace, gentle, flush to my breastbone, unwitting to my shaky hands, and I feel cruel and ashamed of fearing her. The windows are open and the air is sweet.

My family’s stories of death differ: ravenous cancers, refugee camps riddled with disease, public hangings in towns now wiped off the map, bodies contorted in mass graves, 3am can’t sleep YOU WILL DIE panic. Death is, fortunately, still foreign to me. I didn’t know death could be quiet.

She is so quiet.

The morgue is two rooms. The first room is for families of the deceased. It has comfy chairs, flowers, a box of tissues, and a phone I keep on undertaker speed dial. Through a door is the setting familiar to those who watch crime dramas. There are two stainless steel tables — I undo the shroud and slide Mavis onto one — and a large human freezer which takes up an entire wall. It’s frigid and pitch black.

Mavis is dead, but still busy dying.

Chapter 1: Pallor mortis. Mavis’s colour drains as her veins wilt and cease function – she looks as if she saw a ghost. With luck, it’s somebody she loves.

Chapter 2: Algor mortis. I’ve heard you can feel the second a soul moves elsewhere, and the chill kicks in. It’s a black-hole coldness which sucks in the air around her.

Chapter 3: Rigor mortis. I can’t hold Mavis infant-gentle anymore. Her muscles, for all their bedsored atrophy, seize and cramp. I have to slip her, using a plastic board called a patslide, into the industrial-grade freezer, cranking up the trolley because I’m not tall enough to reach the top level of mortuary chambers. Many of the chambers are already occupied by bodies in identical white-zippered cocoons. I close the door softly, like a father saying goodnight, like she pretended to fall asleep in the car. I catch myself hoping that she isn’t afraid of the dark.

Chapter 4: Livor mortis. Later, when I gift Mavis to the undertaker, and I take one last look at her face, her blood’s mottled and turned raincloud purple and sunk to the bottom of her body, eagerly and prematurely pulling into the earth. Her eyes are rheumy, filmed over. I imagine the undertaker to be a man with tailcoats and a horse-drawn hearse. He’s a soft bogan with a lipstick kiss tattooed on his neck and drives a white BMW.

When I get my paycheck later that week, I have received four extra dollars for ferrying Mavis into the afterlife.

What do you do with four dollars in exchange for a life? Do you have to spend it on something holy? Are lolly bags disingenuous? I’m almost certain I spent my first bonus on lolly bags from the dairy, specifically the chocolate orange fish, but I felt weird about it. Here, take this, buy yourself something nice. Keep the change. Feed the body you’ll die in! You’re young and fast and full of A- blood! A couple of choccy fish will help tender the bruise of dispatching corpses at your first minimum-wage job when the 3pm school bell rings, chucking scrubs over skorts in the bushes between PE and ER.

How bizarre to dawdle back into high school class after playing Charon. I did my studies and life went on — for me, anyway. I thought about pursuing medicine, but my grades in science were average, and I don’t think I really wanted to. I was suddenly very popular with goths. Classmates seemed to think I was a mortician and asked lots of questions, like if corpses fart or get erections. (They do, if you’re wondering, but I never experienced this. All our gas and blood has to go somewhere.)

The most mystifying part of it all was just how demystifying it was. I am terrified of death, but not the dead at all. Maybe it’ll be different with somebody I know; I dread the thought of it. All the bodies I dispatched were total strangers to me, not even seen in passing during my shifts. How strange to think that one day, everything I’ve ever thought and feared and loved and experienced may be nothing more than $4 to a pimply teen.

I don’t remember what I spent my corpse funds on, but I do remember quitting shortly after. It wasn’t the bodies: my relationship with Mavis taught me that they were quiet, innocent. It wasn’t the incorrectly inserted catheter vomiting blood from a geriatric penis, or the man I carried from the rescue helicopter, his face stripped into dangling ribbons. The worst thing I saw was a pack of orderlies, fighting over who got to dispatch a stillborn to the morgue.

All for an extra $4.

Names have been changed to protect identities. “Mavis” is not a real person, but an amalgamated stand-in for the many bodies I dispatched.