In the second part of a new event series looking at the future of Auckland, The Spinoff and Auckland Council host In My Backyard: Glen Innes, to ask what the suburb can teach the rest of the city about housing.

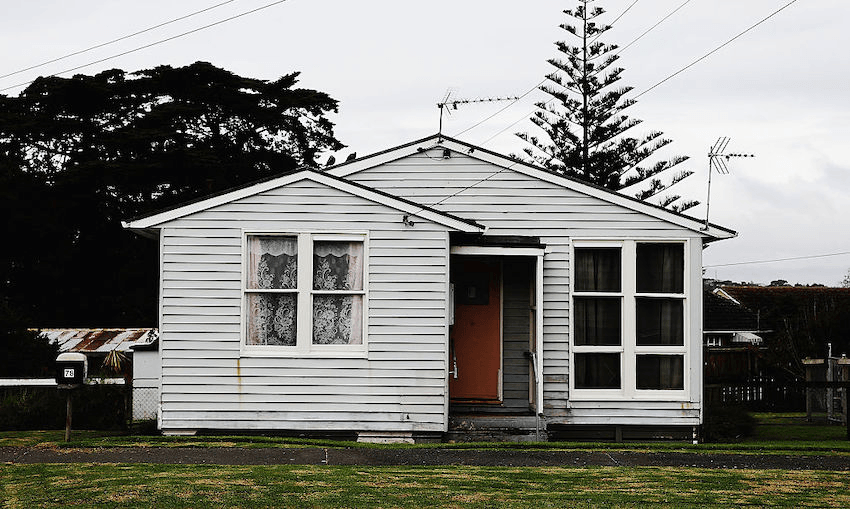

Throughout its history, Glen Innes has had the highest density of state housing in New Zealand. At the start of the decade, a project began to regenerate the area’s tired housing stock. The Tāmaki urban regeneration project plans to build 10,500 new homes in Glen Innes, Panmure and Point England. There will be 3500 homes sold on the open market, 3500 affordable homes, and 3500 new state homes.

Fenchurch St in Glen Innes is filled with new houses. Most of them are terraced houses. State homes and new private houses are mixed together, indistinguishable from each other. They’re all classic modern designs; made of weatherboard and painted in white, off-white, grey and dark grey. It looks like a model for a future Auckland. The development is compact, serviced by public transport, and filled with public spaces. Kids ride home from school on their bikes. The community is both ethnically and socio-economically diverse. There are jobs and opportunities.

But it took time and pain, a lot of mistakes and a new approach to building communities to get here.

Less than 10 years ago the same area was the site of pitched battles. There were arrests and demonstrations. Protesters staged sit-ins in backyards and driveways. The protests were against the plan to demolish 2800 ageing state homes and replace them with 7500 new dwellings (now 10,500) in Tāmaki – the area encompassing Glen Innes and neighbouring east Auckland suburbs Panmure and Point England. The plan meant moving dozens of state housing tenants out of their homes. Critically, not all of them were offered accommodation in their area. Some had been living in their homes for decades.

Come and join The Spinoff for a lively discussion on what Glen Innes can teach Auckland about housing.

November 19, 6-8pm, Te Oro, 98 Line Road, Glen Innes. Please RSVP to kerryanne@thespinoff.co.nz

Then in 2016, the Tāmaki Regeneration Company (TRC) was charged with taking over the Tāmaki development. The job now was not just to progress development, but to improve the relationship with residents, particularly in Glen Innes. Those who had moved out of Tāmaki already were encouraged to get in touch with TRC if they wanted to move back.

However, the community still feared the project was more about gentrification than urban renewal. TRC started building differently in response. All its new development contracts included extra state housing. It worked with local business owners in an effort to ensure Tāmaki’s town centres continued to meet the needs of the current residents.

TRC’s broader mission extends into economic and social transformation. As part of its expanded remit, TRC founded a jobs hub, which has helped 600 Tāmaki locals into employment so far, including 13 members of one whānau. It also helps residents with financial literacy. Some of them have been able to buy their own homes as a result, sometimes by taking advantage of TRC’s shared ownership scheme. The organisation is staffed by a number of locals and reflects the diversity of the Tāmaki community.

Local residents see a community that is safer, where locals have an opportunity to own their homes. But concerns persist. The trauma suffered by the people of Tāmaki – particularly in Glen Innes – will take time to heal.

The area desperately needed regeneration. Many of the state houses being replaced are old, cold and rundown. They make children sick in the winter. They can be tenanted inefficiently. Some 600 to 800 square metre sections are home to one elderly person while others are home to whole extended families.

It’s still early days for the Tāmaki regeneration project, which is expected to run for two decades. Earthworks are already under way on multiple sites across the area, with large-scale developments in the pipeline for Glen Innes and Panmure. A community that has already experienced massive upheaval is about to experience more. Change is inevitable. But it is also required. And Auckland can learn a lot about how to house its residents, without disconnecting them from their communities.

This content was created in paid partnership with Auckland Council. Learn more about our partnerships here.