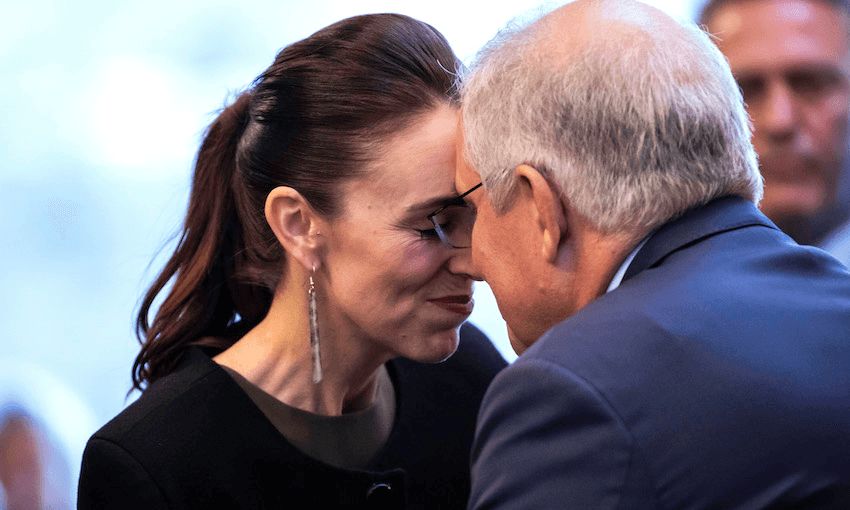

This week, Judith Collins came under fire over a response to a racist tweet that equated Jacinda Ardern and Scott Morrison’s sharing of hongi with an ‘uncivilised’ butting of heads (she had misunderstood its meaning, she later clarified). In this extract from their new book Tikanga, Francis and Kaiora Tipene explain the tikanga of hongi, and how we might rethink our habits around it.

As soon as everything touches, we breathe in together. We close our eyes. Then we lean back and say “kia ora”. That can be before or after. It means you are no longer visitors. We are one people.

FRANCIS

There is a famous saying: “Tihei mauri ora”. It gets translated many ways. Sometimes, the idea of a sneeze is in there, but it always means “the breath of life”. It is used on the marae to get people’s attention at the start of a speech.

A hongi is similar – it is the act of sharing the breath of life with someone. There is a connection.

When we call visitors onto the marae, there is the pōwhiri process: visitors come on, sit and converse. You might hongi first, depending on the kawa of the area. Or it may be after the speeches that we will seal the deal with the hongi. It is much like a handshake in other settings. Shaking hands joins people together physically. We do that when we hongi and we put our nose to the other person’s nose and make sure our foreheads – where our brain and thoughts are – touch as well.

Then we are going to have a hongi. And when we hongi, we breathe in together. It is not a race. We don’t say, “One, two, three, go.” As soon as everything touches, we breathe in together. We close our eyes. Then we lean back and say “kia ora”. That can be before or after. It means you are no longer visitors. We are one people. We have shared a breath through the nose. We have shared thoughts. It’s all symbolic and it’s a beautiful way to connect with one another. It’s a beautiful thing to be able to get intimate like that.

To non-Māori, it can be a bit much getting hard out into someone’s space like that. I’ve hongied a few Pākehā people and they say, “Oh, my nose is so sore.” Maybe. When you grow up with it, your nose gets used to it.

It’s just a touch. We don’t push noses like two bulls having a fight. I’ve heard some orators saying, “Now we are going to press noses.” It is not even pressing. Then it is on to the next person. I love what it means.

A lot of people don’t want to do it, and they are not forced to. If they are uncomfortable, they are uncomfortable. But the hongi and what it signifies is so beautiful. When you walk on the street or through the mall and see someone and have a hongi, a lot of people stare. But the more we do it the more normal it is.

When we hongi Pākehā people, we shouldn’t make out as if they know what it’s about. It’s not about having a smell. We should have a little kōrero first to explain about sharing one breath and one mind and how we are unified when we do that.

Covid-19 changed that a bit. People are even more wary now, especially the elderly. When we took a tūpāpaku to a marae during the pandemic, as we went around for the hongi and harirū, those with respiratory conditions just bowed, so you knew not to hongi or kiss them.

There is other tikanga around tūpāpaku and the hongi. Up north, with our dead in the casket, we are supposed to get down to hongi them.

I need to think about that. They are dead, so we can’t actually share a breath. Down the line, at Gisborne and Tairāwhiti, they don’t touch the body. They just look at it. I think that tikanga is good. They are dead. They are a shell. There is no point to having a hongi with them. They can’t do anything in return.

We need to nip all this social kissing in the bud and get back to the hongi. Kissing isn’t very Māori, but on marae it’s become normal now to kiss ladies and hongi men. I think it’s unfair. It’s like saying the ladies are not Māori but the men are. The kiss is not part of who we are.

I now make every effort to hongi a female in that setting. On the street, a kiss is okay, but on the marae we have to go back to what the hongi is about – connecting together through the nose and mind. That is more in line with kawa.

This is one of those things that is going to take a generation to change. It’s a bit like changing to healthy kai. Bread is easy and goes a long way. Even though we know it is a bit bad for us, we can’t just take it away and switch to salad overnight.

We need to talk about these things more and discuss them, so everyone knows what is expected. At the moment – even when I go to a home to uplift a body – it is automatic for people to kiss or harirū. Or it will be, “Kia ora, Francis,” with a kiss from the wahine and a hongi for the tāne.

“Am I not good enough for a hongi?” a woman asked me once, when this happened. But it is just what we have got used to. So much so that it feels a bit weird giving a hongi to a woman. It shouldn’t be.

I’m not saying this is something we need to do every day, like when we go into work and say hello to our colleagues. It should still be a bit special – for people we haven’t seen in a long time, important visitors, after a formal ceremony or when whānau come into the funeral home, if I haven’t met them yet.

It’s about making people feel comfortable. If people want a kiss instead, they get one. But in the chapel here, I explain the hongi a bit and educate them. There is a fine line between being a funeral director and a tikanga Māori adviser. It’s all in the same realm and how you convey the message is important. It’s in the delivery, which needs to be subtle and gentle.

KAIORA

In my younger days in Te Tai Tokerau, we only saw males do the hongi. I was educated to think that was correct. Only later did I start to see many women do it, and now it is an everyday thing for wāhine. I like that. If you haven’t seen someone for a long time and run into them at the bank or the doctor’s or a café, you give them a hongi.

There are some people who are very staunch with their greeting. The hongi is their way of acknowledging and accepting someone when they meet them.

When it comes to people giving each other kisses, sometimes I feel awkward. You see them going in for the kiss and getting it wrong. There have been times when Francis has ended up kissing someone on the nose because he wasn’t sure what was coming. “I kissed Whaea on the nose! It turned out she wanted a hongi but I didn’t know that, so I kissed her nose.”

There have been a couple of conferences where Francis and I have educated people on how to hongi. We have lots of examples from our own experience of what not to do – no kissing the eye, no kissing the nose, no rubbing your nose on the cheek.

It will be a long time before we see two Pākehā hongi each other as a normal greeting, but everything can change and people have already got used to many different things. Perhaps that will be one.

Tikanga: Living with the traditions of te ao Māori, by Francis and Kaiora Tipene is out on Wednesday and can be preordered from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.