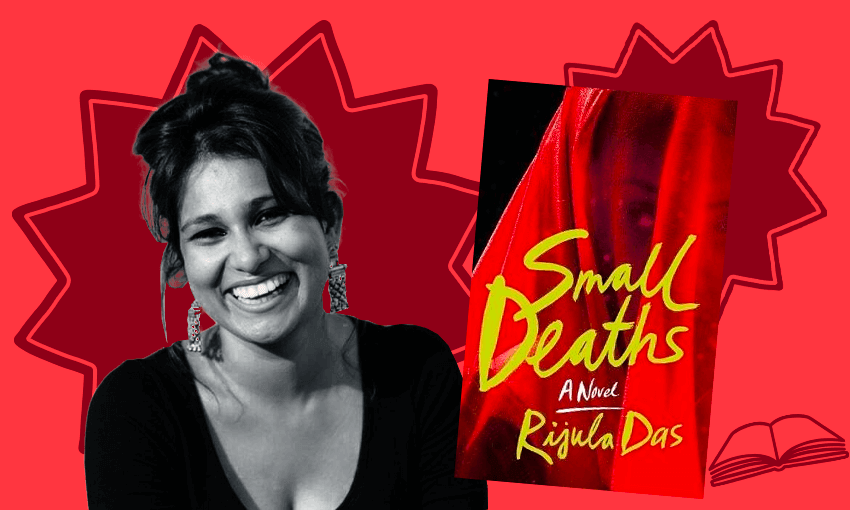

Sam Brooks reviews the award-winning, soon-to-be-adapted-for-television debut novel from Rijula Das.

Genre is a fascinating thing. It can be a comfort, where an author can use familiar tools to put an audience at ease – everybody knows what they’re selling, everybody knows what they’re buying. It can be a crutch, a series of tropes allowing an author to hobble through problems they can’t manoeuvre with craft alone. It can also be a cage, the familiar framework holding a story and its characters back from achieving true greatness. Or it can be something to challenge, something for an author to look at, and write in active defiance of what has come before, what the genre can be.

Small Deaths, the debut novel from Rijula Das, finds itself relating to its chosen genre – noir – in all these ways, some at the same time. It’s an experience that, while never boring, can occasionally lead to the feeling that you’re reading a book that is in conversation with its genre rather than embodying it. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

The story is set in Shonagachhi, one of the most notorious red light districts of Kolkata, and while it follows a fairly large cast of characters, our two main hooks are Lalee, who was sold into sex work as a teenager by an uncaring father, and Tilu, an aspiring erotic novel novelist whose one indulgence are his visits to Lalee. One evening, one of Lalee’s co-workers is found brutally murdered across the room from them, and what follows threatens to unravel the precarious, and bleak, existences they’ve managed to eke out for themselves.

It’s a classic noir set-up, albeit one that Das slyly subverts. In another noir, you’d expect Tilu to be the hapless protagonist lured into a life of crime by Lalee, and for us to see the world through his lens. However, while we do spend some time in his head – creating erotic historical fantasies – it’s Lalee who we spend the most time with. And it’s Lalee’s determination to find out what happened to her friend that moves the plot along, even as she finds herself drawn into a plot that has wider implications than her life.

There’s also obviously the location – Shonagachhi provides Das with a whole range of ephemera and environment to surround her characters with, less cliché than a smoky bar in New York or a detective’s office in Los Angeles. Little details like “a half-broken, non-airconditioned Bank of Baroda ATM”, a man cooking a paan on the side of the road, and a “shitty-two room chamber with stained walls above an umbrella repair shop” ring true. There’s still familiarity of course – immorality does tend towards familiar images and expressions – but Das’s prose revels in the opportunity to point a lens where it hasn’t been pointed before.

That subversion is remarkably refreshing; none of the sex work, or the workers, is treated for titillation purposes, but treated for the work, and sometimes the exploitation, that it actually is. A subplot, featuring a burgeoning community movement fighting for the rights of sex workers, emphasises this fact. Noir has been a genre that has historically treated its characters, especially its women, as archetypes (sex worker with a heart of gold, femme fatale, blonde bombshell) that, while familiar, tend to flatten characters (and therefore the story), rather than illuminate. It’s exciting to see Das subvert these with characters who are more than archetypes, or even more electrically, who know the power of an archetype and when to play into it for their advantage, because it’s often the only advantage they have.

This is especially true when it comes to Tilu, for whom Das has sympathy without ever indulging the character’s ridiculous fantasies and dreams. It’s an aunty’s compassion; it comes from someone who will dress you down for your every flaw and failing, but then welcome you in for a cup of tea and a biscuit. It doesn’t make the novel a light read – it is full of characters who willingly screw over each other – but it lifts the foot off our throats just a little bit.

There can be a sense of monotony to the book that isn’t any fault of Das’s prose, or her plotting, but simply the nature of the genre. Things aren’t going to get better for most of these characters, only gradually worse. We’re seeing a snapshot of their lives at a pivotal moment, but there’s a sense that there’s an upper limit to how happy anybody can be in Shonagachhi.

It’s to Das’s credit that the novel never gets dull, but the tension can at times feel slightly oppressive rather than propulsive, not an ideal quality in a thriller. I found myself wanting to step away from the book because that felt like the only way to relieve pressure, to turn off the steam valve, because I knew the book wouldn’t provide it for me. (This is absolutely a taste thing, I should note that I have the same problem with the Game of Thrones books, and those aren’t wanting for readers, acclaim or general cultural ubiquity.)

While Das’s conclusion is not an inevitable one, and in fact it reveals a compassion for her characters and their situation that most noir famously lacks, the trajectory feels like a foregone conclusion. It’s here that Small Deaths finds itself in a cage – a bleak first act and a bleaker second act doesn’t exactly lead to a Sound of Music-type ending. A novel that begins with a sex worker dying doesn’t end up with a miracle resurrection, an upheaval of society, or a reversal of misfortune. It might, if the reader is lucky, end up with a small light of hope, a lit match inside a smoke-filled bar.

Sitting with the novel after the fact though, it makes me wonder if maybe the neatness was the point. Maybe noir and Shonagachhi are a perfect marriage not because Das has decided it to be so, but because the heart at the core of noir, the one that pumps black blood into its veins, is a perfect match for Shonagachhi’s soul. If that’s the case, then the compassion and the grace that Das gives her story and its characters is a relief, a quiet defiance, in itself.

Small Deaths by Rijula Das (Amazon Crossing, $29.99) can be ordered from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington. Rijula Das is programmer of Verb Readers & Writers Festival, 2 – 6 November in Wellington.