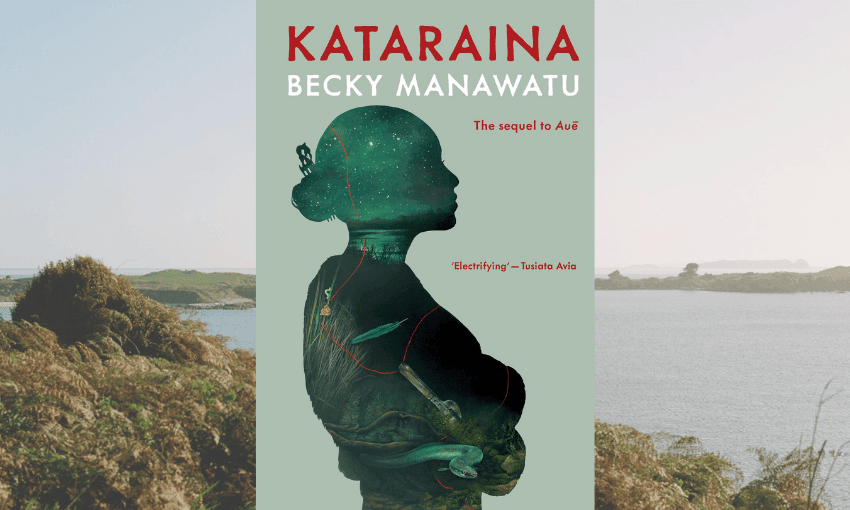

Jenna Todd responds to Kataraina, the sequel to Becky Manawatu’s award-winning first novel Auē.

This review contains major spoilers for Auē.

Many years after the girl shot the man.

I’d almost forgotten who had shot the man in Auē, winner of the Jann Medlicott Acorn Foundation Prize for Fiction in 2020. When I open the sequel, Kataraina, I am projected back into the world of the Te Au whānau with urgency. Of course it was the girl. But it was also all of them.

This is the dramatic climax of Auē. Young heroes, Ārama (Ari) and Beth. The dreaded villain Stu, Aunty Kat’s abusive husband. Lupo the dog. The house on the farm. Taukiri, Ari’s brother and Tommy, the neighbour. Kat, beaten again. The gun. Stu, dead. Kat has been a shadow throughout Auē, surviving, while also being the person that connected the characters together. How did she get here?

Kataraina fuels a need for more of Aunty Kat’s story. Not just for the reader, but also for Becky Manawatu, “I had to write something connected to [Auē] because there was more to do, I wanted to give some context of how it got that far, let her speak a lot more.”

Less plot driven than Auē, Kataraina is enriched with frames of reference to the past, with a majority of the chapters time-marked to the shooting. The jump in maturity of Manawatu’s writing is immediately apparent: there is a marked growth in style and confidence. Manawatu aimed for the tihi of the mauka and hit it. The narrative is confident and assured in its structure, as is the precious matauraka of our iwi: the hard k of our Kāi Tahu dialect is unmissable, our karakia, our whenua, our rauemi.

Time isn’t linear and we move back and forth through vignettes and snapshots. Scenes from years earlier: Kat, the baby of the family, with her older twin siblings, Toko and Aroha. A close bond with her imperfect grandparents, Nanny Liz and Jack. Her parents, Colleen and Hēnare, in their house by the sea. Kat as a seven-year-old, with her whānau in the kitchen. Kat as a teenager, with cousins around the bonfire.

Textures of domesticity fill Kataraina with scenes of whānau life. The comfort kai of dreams and memory touchstones brings the family together and is central to their interactions: ice cream, kaimoana, raro, white sandwich bread, sponge, boil up, all the chips – hot, ready salted, salt and vinegar. But kai also brings a sense of foreboding: a can of peaches, toasted sammy, bolognese.

As Kataraina steps into her mid teens a toxic relationship – “a seeping rot”, “a greenness” – begins to poison her sense of self worth: “…she chose fuss. She chose trouble. She chose attention, even if she didn’t really want it, even if she’d rather disappear. This was the mess, she realised now, when your survival instincts were tampered with. You might choose danger to remind people you exist or defibrillate your heart.”

Throughout the book, a third person perspective allows for a chorus of whānau, past and present, to tell their story. “There had been moments where Kataraina believed her family was one entity, one body, moving towards something so incredible, and she was both in awe and afraid.” The rupture of Auē’s climax belongs to all of them. “Our ‘we’ has no beginning, will not end.”

The natural environment cradles the narrative and our characters as Manawatu’s effortless figurative language is intertwined with the languages of science: lush ecology, resources and knowledge sits in the deep fabric of the environment. There is poetry in lines like this: “Meaty rain clouds wring the mountains’ necks, but the sky near the coast is bright white and light gold.”

The central landmark, breathing as its own character, is Johnson’s Swamp, the kūkūwai on Stu and Kat’s farm. Kat, as a young schoolgirl, sees this too, “I’m reading about how wetlands store a sort of historical record. Like in peat, like in the water and earth. That even water holds memories. So, yeah, science in history.”

Enveloping the secrets, stories and evidence of those around her, the kūkūwai’s story is a vehicle for new characters to be introduced across vastly different time periods. In early 2020, Kāti Kuri scientists Cairo and Hana work within a group of researchers. Straddling Te Ao Pākeha and Te Ao Māori, the field study asks, “What was the main water source contributing to the massive increase in both the circumference and depth of Johnson’s Swamp?” Clues are given as we are introduced to tīpuna Tikumu, 128 years before Stu’s death. In a space of colonial invasion, evidence is left behind.

Manawatu is my whanauka. We were standing together in the blue haze of the Gala night after party at the Auckland Writers Festival in May and discovered our shared whakapapa about five words in. Our tīpuna, Tamairaki Mere Te Kaiheraki, is buried at Te-Wehi-i-Te-Wera The Neck, a headland to the east of Rakiura Stewart Island. For most of the 19th Century into the 20th, The Neck was the home of up to 200 families, mostly of mixed descent whānau, made of wāhine Māori and Pākehā whalers and sealers.

Tamairaki is immortalised on a pou alongside a group of mana-wāhine Māori within a tītī hut-shaped wharenui at Te Rau Aroha Marae in Awarua Bluff. Designed by Cliff Whiting, the bodies of each pou wāhine can be opened. Each tinana pataka are a vessel where whanauka can leave behind taoka, pānui and koha.

Pre-treaty, the population of Southern Māori decreased rapidly – in 1835, an estimated 4,000 were killed by measles. The group of mana wāhine depicted within the wharenui of Te Rau Aroha Marae are celebrated because their marriages to Pākehā men ensured the survival of our people.

Why do these stories of our tīpuna matter to this review? Because Kataraina is all about the horopaki, the context. To know the Te Au whānau, we have to know the whole story. The complexities and contradictions of being human, kūkūwai and all. The fierce importance of connection to our tīpuna and the foundations they have laid to ensure we are here now.

Wāhine are the healers in Kataraina. Even as some exist with a neverending tension of living with a volatile partner. Hēnare, Kat’s Dad, describes his Māmā (Lizzy) as a kidney, rather than the heart of the whānau. “Tell her something that’s causing an ache for you, and she’ll run it through her own flesh. She’ll let it clunk about in her own blood for a bit, purify it for you.”

Kat wants to be this person too – to her whānau, her friends. But there are consequences, as Stu (an asshole from the beginning, but given the grace of context also) exerts his threatening and consequential energy around her: “She was a mountain, somewhere in her was a peat buried so long it had become black and shiny and precious.”

In Te Ao Māori, we have duality: Papa and Raki, tapu and noa, te kore and te ao. In her interview with Lynn Freeman, Becky describes Auē as a breath in and hoped that Kataraina would be a breath out. In another RNZ interview, Manawatu described Auē as masculine and Kataraina as feminine. (“Did I say that?” said Manawatu in her Auckland Writers Festival session with Irish writer Sinéad Gleeson.) Auē and Kataraina absolutely work in this way. Now, having read both, I can’t have one without the other.

Kāi Tahu women have always been the backbone of our iwi’s survival and generations after have ensured the preservation and living endurance of matauraka, tikaka and reo. Becky’s storytelling cradles this belief – generations of survivors – like Aunty Kat, shouldering through.

Kataraina by Becky Manawatu ($37, Makaro Press) is available to purchase from Unity Books.