Nicola Harvey moved from the city to the country in search of the good life. Instead, she discovered an industry divided over the climate crisis, including those closest to her.

“Do you talk to your mates about climate change,” I asked my dad and uncle one afternoon as we sat outside my farmhouse overlooking the front paddock and waterway below. “Well yeah,” my uncle said, “but you lot say it’s a bit more serious than we do”. It is warming, he’ll admit, but most of his buddies won’t say it’s because of farming.

“There’s always been warming on the planet, what about the millions of buffalo gone?” my dad added. Methane has always been emitted, it’s just cows now rather than buffalo herds doing the burping.

I had this conversation almost two years ago in the wake of an International Panel for Climate Change report that stated that a shift to more sustainable food production offered the best chance to tackle climate change. A global problem required a global solution, and the focus swiftly landed on the wide-scale adoption of a plant-based diet with calls to reduce meat and dairy production and consumption globally. In Aotearoa New Zealand, a country that exports around 20 billion and 9.6 billion worth of dairy and red meat respectively, farmers read it as an attack on their way of life and livelihood, and a belittlement of the contribution the primary industries make to the economy. Farming isn’t to blame, my dad implored.

I wasn’t so certain.

I’ve lived on a beef farm north of Taupō for more than four years. But I am not a farmer. I make a living from the fattening and selling of cattle but I don’t see the world as my father does. He remains wedded to an identity that stems from the image of hard men in black singlets clearing land during a time when the government incentivised, through grants and subsidies, the draining of wetlands and back burning of mānuka to create productive farmland.

For most of my adult life, I’ve lived and worked in big cities: Melbourne, London and Sydney. I built a career as a journalist and media executive and then I burned out and moved home to Aotearoa with my Australian husband. A vision of earning a living from the land and growing good food loomed large.

But the decision to quit city life in 2018 to become a cattle farmer dropped us amid a cluster of arguments about food and farming and its role in causing and combating climate change and the degradation of land, fresh water, air. And, like so many others, I went looking for someone to blame for our collective woes. Someone who looks a lot like my dad.

I wanted to know why his generation drained the wetlands, why the amount of New Zealand land under irrigation jumped from 384,000 to 735,000 hectares between 2002 and 2012, and why the annual use of nitrogen fertiliser has increased six-fold since 1990 from 59,000 tonnes to more than 400,000 tonnes.

I wanted to know why productivity was privileged while the polluted water, the changing climate, and the vast divide opening up between people who produce food and those who consume it went unaddressed for decades.

But I stopped picking fights when the floods started. First ripping across long dormant flood plains in Canterbury in 2021, then drowning West Coast townships, overflowing water systems in Napier, and most recently swamping Nelson causing slips to crash into homes washing away cherished memories and assets; each as valuable as the other.

The need to change was suddenly urgent and I didn’t want to hear why my dad disagreed with the government’s freshwater and climate mitigation policies. I stopped listening and instead latched onto anything that felt like climate action.

On the farm, we stopped using synthetic fertiliser, stopped sowing winter crops to feed our cattle, encouraged worms and fungi in pursuit of healthy soil, and slowly cut back on inputs in an effort to decarbonise. We followed the lead of others who long ago concluded that working with nature, not against, was the future of farming.

I started sourcing vegetables from Misfit Garden – a business that sources “waste” produce from farms and growers who can’t meet the timing or aesthetic requirements of the supermarket contracts. Clothes were purchased second hand and mended, all meals were cooked from scratch, travel was limited, holidays were local. I tried to grow vegetables and kept the seeds. The self flagellation of DIY labour felt like climate action. But has it made any difference?

The United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration released its annual State of the Climate report on August 30 and the findings were grave: carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide levels all increased in 2021. The following day, I received a press release from the self-appointed farming advocacy group Groundswell announcing a tractor rally on the Auckland Harbour Bridge was planned as part of the group’s “Say No” campaign.

They’re urging land owners to Say No to surveys on private land, no to using “government-controlled” farm plans, no to calculating one’s farm emissions number, and no to requesting resource consent for winter grazing; all environmental regulatory measures introduced by the Labour government.

When just ten tractors showed up for the protest I dismissed the group’s obstructionist message as a stunt. But this week, NZ Farmers Weekly carried an open letter signed by a consortium of conservation-focused beef and sheep farmers pleading with their elected lobbying groups to reject He Waka Eke Noa, the primary sector programme designed to keep farming businesses out of the emissions trading scheme. The letter writers worry He Waka Eke Noa won’t result in environmental gains. All it will do is facilitate “widespread afforestation, community devastation and the further intensification of land remaining in partorial use”. Climate mitigation programmes are changing the land around us. That is easy to see. And yet the calls to slow the roll out of these environmental regulations or change track entirely get louder.

Recently, the Overseas Investment Office approved the sale of four sheep and beef farms to overseas investors. More than 7000 hectares will be planted in rotational forests to offset the activities of companies like furniture maker IKEA, whose parent company Ingka Investments purchased 6000 hectares of farmland in the Gisborne region.

And not far from where I farm a vast dairy farm will be converted into the country’s largest solar farm. Pine trees, wind turbines and solar panels are replacing sheep and cattle, and for many who’ve spent their lives living on the land and consider themselves good stewards the change is visually devastating.

I was reminded recently on Twitter that many farmers aren’t so much disinterested in climate action as uncomfortable with not knowing if the changes recommended in He Waka Eke Noa and other climate-related policies will have the promised effect. They’re fearful that we could collectively be doing more damage than good. But I’m fearful that those who are Saying No, and arguing over mitigation strategies instead of acting, are leading us all toward inertia.

Professor David Frame, a climate scientist who has been the lead author on two Assessment Reports for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, told me plainly that we can’t afford another two generations driving vehicles powered by fossil fuels. The planetary reserves will be spent if that happens. I come back to this statement often when I survey the division. Our collective future will and must look different. Some like my dad will remain fearful and won’t change. But more of us will.

When my husband and I arrived in Aotearoa to farm, we slammed against each other to build a business, a life, something bigger than ourselves. The difficulty of farming fractured something between us, but not irreparably. A psychologist I spoke to told me that a space exists between two people that needs to be nurtured and fed for the relationship to flourish. I don’t need to convince Pat to be more like me, nor I more like him. The feeding will ebb and flow, but someone will always nurture that space, and the result is togetherness.

It’s an analogy that can be applied to our collective will to curb climate change. We don’t need to mirror each other in ambition, ethics, and action, but we all need to keep feeding the space that will slow the warming. Together but apart.

Learning to darn socks may seem like the smallest of actions in this age of fast fashion but it all adds up. Profound activism can be found in the decision to do and buy less. And it seems far more productive this week than arguing about farming’s impact on climate change with my dad.

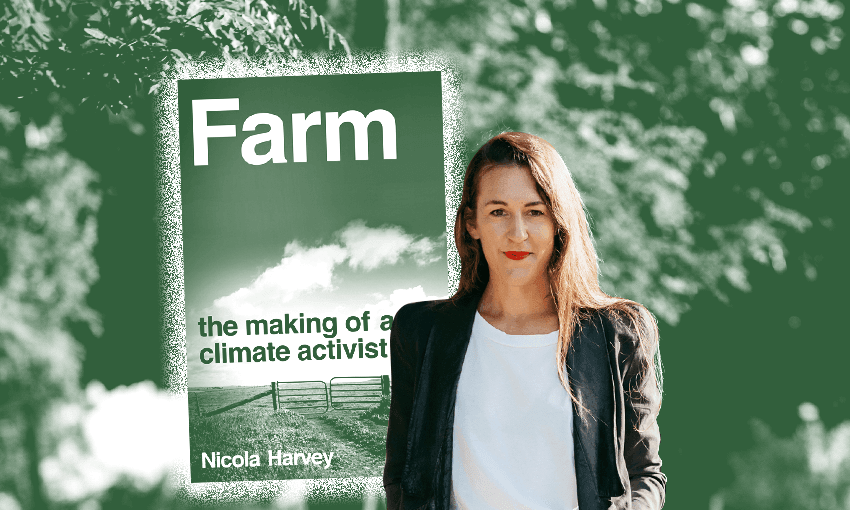

Nicola Harvey is the author of Farm: The making of A Climate Activist (Scribe, $37), available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington. Nicola will be in conversation with writer and broadcaster Noelle McCarthy at Unity Books Wellington on September 8 at 6pm.