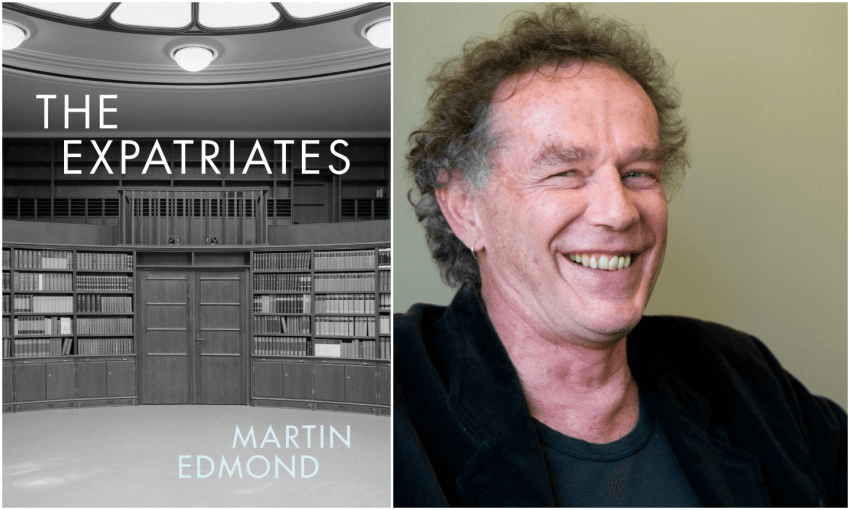

The high priest of New Zealand non-fiction, Martin Edmond, reveals the curious genesis of his latest book.

One day in the summer of 2013 I received a letter from James McNeish. He said he had a proposition to put to me – but that I would have to go to Wellington to find out what it was. I flew in from Sydney in February of that year and, the day after I arrived, rang James from my sister’s place in Roseneath. He said come over. I walked down Grass Street, by my mother’s old house at number 22 (it looked neglected), past my grandparent’s former flat where my parents lived, sleeping in a single bed, after they were married, through the scintillations of light glancing off the sea at Oriental Bay and on into the city.

Wellington is to me a conundrum. My first city, if not my last. Past, present and future are so mixed here I am unable to say what is actual, as opposed to what may be imagined or remembered. This could of course be a life condition. I went on down Courtenay Place, Manners Street, Willis Street. Ghosts thick on the pavements; future ghosts, ghosts of the living, gone ghosts. From an arcade on Lambton Quay I took an elevator to the James Cook hotel and exited onto The Terrace, where the McNeishes lived in two small flats in a modest building.

Mindful of the complexities of his entrances, James met me in the foyer and ushered me up to the eighth floor. His wife, Helen, had a different apartment, looking a different way, on a different floor: a sensible arrangement, though it did involve them in quite a lot of to-ing and fro-ing. They took morning coffee together, or lunch, or afternoon tea. One evening I had dinner with them in Helen’s place, which seemed actually to be situated in some European city – Prague perhaps, where she was born.

James’s place too was exotic, though I couldn’t work out exactly where to locate it. Somewhere between London and Jerusalem? Anyway, it is a privilege to visit an admired writer’s working space and I was avid for looking and remembering; by the same token, it seems indiscreet to reveal too much about it. Suffice to say that it was sparse, orderly, comfortable and with an indefinable sense of intrigue: as if mysteries were enacted there daily. A scent / as indecipherable as Moscow.

On that first morning James made coffee, set out a plate of biscuits, and sat down opposite me at the table. It was time for the proposition to be put. He said he had amassed a great deal of material during his research for Dance of the Peacocks and The Sixth Man which he would not be using in any further writing projects. Would I like to look through his files to see if there was anything there of interest to me? Would I! Of course I would. How long did I have? he wondered. I said three days. That should be ample, he said. He suggested I spend those days in his apartment, reading through files, which he would supply; and then, if anything came to mind, we could take it from there. I’ll be in and out, mostly out, he said. I won’t disturb you.

He was as good as his word. When, after walking across the city and taking the lift to The Terrace, I arrived at his place a bit after nine each morning, he would already have completed his writing for the day and was on his way out to do other things. He usually came back for lunch, and at the end of the day, but otherwise I hardly saw him. Once Helen joined us for coffee. Mostly I was alone with his files, behind glowing rattan blinds that masked windows looking north and east over the harbour.

The files themselves were things of beauty. They resembled James’s apartment: sparse, orderly, with a strong sense of intrigue. They were like intelligence dossiers assembled by a consummate spy-master. Many entries were typed on A4 paper using the courier font; some just a sentence or two; others pages long. They were the fruit of a conversation or an interview; notes to self or notes from reading. There were documents, photocopied from disparate sources. Some personal letters. A few photographs. Reports gathered on James’s behalf by other researchers. They were loosely arranged as files on various individuals, most of whom I had not encountered before. Each morning there was a new pile set out for me to read.

I suspect these dossiers were an outcome of a long period of focussed inquiry going as far back perhaps as the research for James’s 1986 book on Jack Lovelock. It was a remark of James Bertram’s that set James McNeish onto Jack Lovelock: Bertram, who knew Lovelock at Oxford, called him “a young god under strain”. That piqued McNeish’s interest. Lovelock was a Rhodes scholar and subsequently James became interested in finding out the fates of other Rhodes scholars; and, more generally, what happened to talented New Zealanders who, for one reason or other, ended up spending most of their lives overseas.

James, who had himself spent long periods living abroad, and an even longer period living in a very remote part of the country, glossed his interest in these figures as a way of coming to an understanding of what might be called the national character. He was deliberating upon a book, tentatively entitled The Fatal New Zealander, after Sebastian Faulks’s The Fatal Englishman. Who are New Zealanders really and what are the factors that have made us as we are? I don’t share this interest in “national character” per se but I am fascinated by characters. And there was an array of them in the files.

Over those three days, then, four of the people in James’s rogue’s gallery lodged themselves in my mind. At the same time, I started to intuit a chronological structure in which I could, severally and together, place them; almost as if I were writing a (partial) history of the twentieth century. On that last afternoon, which may have been a Thursday, with the light of the westering sun streaming obliquely through the rattan blinds, glimpses of the blue harbour in the distance, I put my plan to James. This is what I would like to do, I said, these are the figures I want to write about, this is the use I would put to the gift you have offered me. This is the shape I imagine making.

If he was surprised he did not let on. If he had, in some sense, in his own mind, anticipated this was the way I might want to go, he didn’t say that either. He was scrupulous and non-committal, though never unenthusiastic; and remained so for the duration of my writing of the book; which was completed, in draft form, just a few weeks before he died on November 11, 2016.

An extract from The Expatriates by Martin Edmond (Bridget Williams Books, $42.99), available at Unity Books.