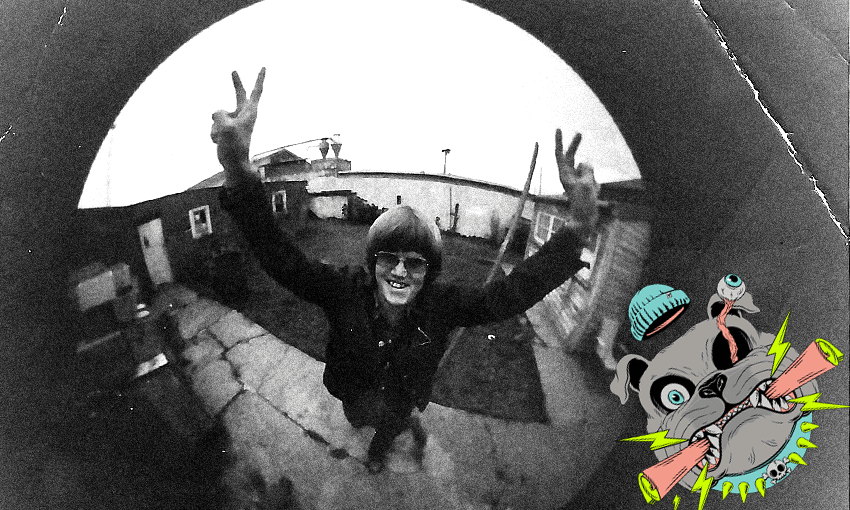

In this excerpt from his new memoir, the man behind Phantom Billstickers gives a glimpse into the life of a junkie in the South Island in the 1970s.

BURGLING A CHEMIST

In which Jim and an accomplice, hereafter known as ‘The Nark’, have a go at breaking into three chemist shops in Dunedin.

My first chemist that night was near the Wakari Hospital. I was just wheeling out the cutting gear through the car park when a bread delivery van pulled in. I stood and folded my arms and stared down the driver, the oxy-acetylene gas cutting gear was standing beside me. We had to lift the cutting gear onto the roof of the shop and drop it down through a skylight. This can become complicated.

The driver of the bread van caught me in his headlights and all around me there were shadows flickering and painting scary images in the dark. But, I’d reached the stage of not caring by then; I’d learned that if you got into the right headspace you could do almost anything and not get arrested. You became the invisible man and no one wanted to acknowledge that you were there.

This particular chemist, at Wakari, had a Chubb combination safe mounted on a concrete wall. It was small and robust and it just wouldn’t cut open. My off-sider and I felt compelled to melt the combination dial all over the front of the safe so that the chemist wouldn’t have been able to get it open either. This is called a win-win situation.

I remember there was a bottle of liquid morphine that the chemist couldn’t fit into the safe and so it had just been left on the shelf. We didn’t even take it with us. We just left it there. We did what we could at Wakari and then we left for South Dunedin. During the process of trying to gain entry to the second shop at Forbury Corner, a taxi driver chased us off. And I guess that’s the way you would want it to be. We were skinny, nervy kids and we scattered.

The taxi driver had been watching too much Hawaii Five-O on television. It was the third pharmacy, at Musselburgh, that was to be the pay-off. The chemist had put six bolts down either side of the back door and so we went in through the front. The shop was not alarmed but it was extremely well fortified. As we worked on the safe with the cutting gear, it sent sparks, shit, and noise into the air, and the whole shop lit up like a Christmas tree. In the spirit of revenge for the bolts down the back door, we set the shelves on fire with the cutting gear.

At one point a milkman, oblivious to us, delivered some milk outside. We drank that milk. We cut an ugly gash around the lock in the safe and the door swung open on the first try. We left there with more than two big rubbish bags filled with dope to the brim. The Nark was a blond-haired guy and a surfie type. He had a clean way about him and a shining look. It would never have occurred to you that he was a junkie. He always looked healthy. You could quite easily think of him as being at a racetrack with a pencil behind his ear and a ‘Best Bets’ in his mitts. Butter would not have melted in his mouth. The Nark mimicked the behaviour and speech of a good, keen Kiwi bloke. This type is always the most interesting sort of junkie.

He worked in an engineer’s shop, off Manchester Street in Christchurch, and so he knew how to handle oxy-acetylene gear very well. By the age of 19, he’d already been sent down to Invercargill twice and had finished two Borstals there. By the time we finished at Musselburgh, we were cold and shivering and wanted to throw up. It was now early morning, and we were beginning to hang out because our methadone from the day before was starting to wear off. We were sick and breaking our necks to get better. When The Nark and I got that safe open at Musselburgh, we just looked at each other and laughed.

Included in the giant haul of dope were about 400 cans of morphine/pethidine and lots of really old vials of syringe tablets, various powders and crystals, and all the other good stuff. There were 1200 Palfium pills and mountains of other tablets. There was also liquid this, liquid that, and liquid the other thing.

This was the last time I ever saw a bottle of Brompton’s Cocktail. I carry a photograph of that bottle in my wallet to this day right next door to a photo of my dear old mum. The Nark and I walked out the door like we owned the place. We were whistling as we loaded up the car and headed the big old Rover down Andersons Bay Road, over the Kilmog, and up State Highway 1, headed for Christchurch.

We didn’t intend to stop for a hit until we got to Oamaru and the road was long and dark as we drove through the Otago hills, and gullies, and along that beautiful coastline with the black sea sparkling on our right. I was driving at around seventy or eighty miles per hour. We were sailing in the poor man’s Rolls Royce and the headlights were cutting out the waves in front of us. The beautiful engine was barely ticking over.

When we reached Oamaru, we stopped at an old gas station at the very north end of the town and on a bend. We drew up water from a hose and mixed up a hit of Omnopon on the roof of the car. Given that these were syringe pills, we could practically do it all in the dark. You throw three or four of them into the outfit, add some water, shake it up and it’s ready to go. After we’d mixed up the medicine, we hovered under the wooden dash and squirted it up our arms.

Omnopon is God’s Own Medicine as everyone knows and after our medication, The Nark and I were feeling more comfortable than we ever had in our lives. We talked for a good thirty minutes about the leather seats in the Rover and about how they had been hand sewn in England and how the quality of English leather was never to be beaten.

You Can’t Put That There! is being released in honour of Phantom Billstickers’ 40th birthday next year. You can pre-order it online on the Phantom website.