The founder of Wild Catch says his job is ‘the ultimate barbecue conversation starter’.

This is an excerpt from our new business newsletter Stocktake. Subscribe here to read more.

James Parfitt has stories. There’s the one about the chilly bin full of sea cucumbers that he took to China in 2009, earning him some strange looks in airports. “I’ve got plenty [of yarns] about border agents,” says Parfitt, the founder and CEO of Wild Catch, a small South Island fisheries company exporting mainly to China. Ever since he started his company, those stories haven’t stopped. “Taking things up to trade fairs, that’s when things get a bit dicey,” he says, launching into a story that involves undercover travel. “I had to cross a few checkpoints quite covertly,” he admits.

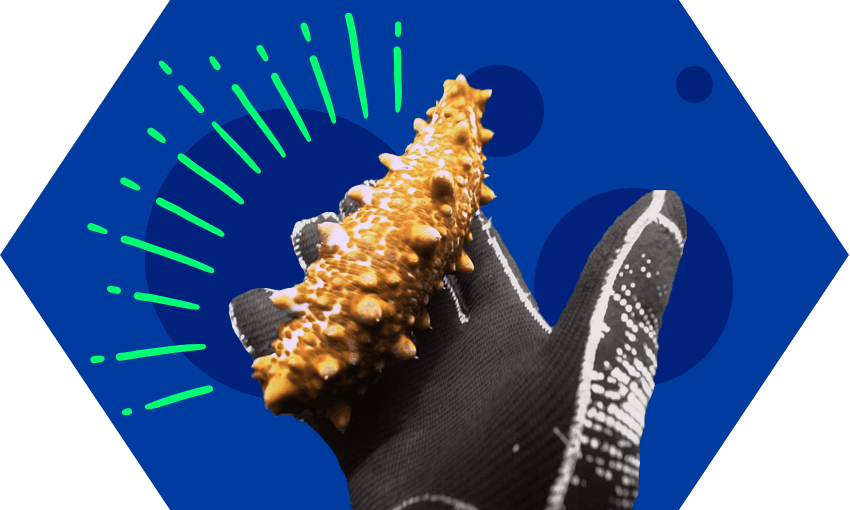

Parfitt’s adventures with tubs of his bêche-de-mer – the official title of his New Zealand-grown sea cucumbers, also sometimes known by the less delicious-sounding name “sea slugs” – make Parfitt a popular person to chat to at gatherings. “It’s the ultimate barbecue conversation starter speaking to randoms,” he says. They ask him: what are sea cucumbers? And, how did he end up catching them in Aotearoa, drying them, sending them to China, and turning his operation into a profitable and award-winning business – a story he’s yet to discuss with a reporter before now? “It’s pretty weird,” Parfitt admits.

They’re all questions I wanted to ask as well. So I gave him a call and asked him to explain everything. “I only have 10% battery,” Parfitt warned. Luckily, it was just enough time for him to tell me how, living in China in the late 2000s, he wanted to create a business that would connect him to his two favourite countries, China and Aotearoa. He befriended a sea cucumber expert who told him how popular the seafood delicacy is there. Parfitt remembered: “We have those in New Zealand. You see them out snorkelling. I used to see them around the Marlborough Sounds.”

So he came home, went diving and rounded some up. A sea cucumber is a little slug-like creature with soft spikes to help it stick to rocks around the South Island. “It’s in the same family as kina, sea urchins and starfish,” says Parfitt. “In New Zealand, they’re a golden colour, making them even more sought after.” After they’re harvested, by hand, Parfitt sends them to his Christchurch factory for drying and packaging. All of this takes time, which is why they’re so expensive. Right now, Wild Catch charges about $4.50 for each dried sea cucumber, while overseas variants can be as little as $1.

Price doesn’t seem to matter, because China is going wild for Wild Catch. After that first haul, Parfitt realised his sea cucumbers rated extremely well with customers. Overseas competitors farm sea cucumbers in less than ideal conditions, Parfitt says, using antibiotics, hormones and filthy water. Parfitt’s sea cucumbers are caught wild and, he says, sustainably. “We got some pretty good results and feedback and the texture was very similar to the really highly prized Japanese species – only ours were wild and a golden colour,” he says.

Once they make it to tables in China, sea cucumbers are eaten as a superfood. “Big chunks of populations will have one a day all through winter to ward off sickness and keep healthy,” says Parfitt. They can be cooked in many ways. “They carry the flavour of whatever they’re cooked in. At a banquet you might get served one on a plate by itself with minimal garnish or it might be in a big stirfry or a soup. It can be cooked in hundreds of different ways.” Some also consider it to be an aphrodisiac, but Parfitt says “that’s not something I can vouch for”.

What he can vouch for is how well Wild Catch is doing. Despite a small slump when Covid hit, he’s back to exporting nearly a million sea cucumbers a year. Parfitt’s hoping to grow that market and has big ambitions, aiming to make his sea cucumbers the biggest seafood exported out of New Zealand. He’s got a long way to go: the Ministry of Primary Industries estimates seafood exports topping $1.5 billion a year, including lobster, mussels, squid and salmon. He admits it’s a competitive industry, which is one of the reasons he’s been laying low, not wanting to draw attention to his “niche”.

But awareness is growing. Parfitt has several awards to show for his business efforts, including an NZTE award for trade between New Zealand and China, and a recent nomination in the EY New Zealand entrepreneur of the year awards. He knows he can’t keep his business secret much longer, because the sea cucumber market is growing. He promises to send me a list of Auckland restaurants cooking with Wild Catch’s sea cucumbers, and I promise to try them. He remains a fan himself. “I love them,” he says. “They’re such a clean-tasting food. They’re not fishy at all … it’s a really healthy food that makes you feel alive.”

Follow Business is Boring with Simon Pound on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.