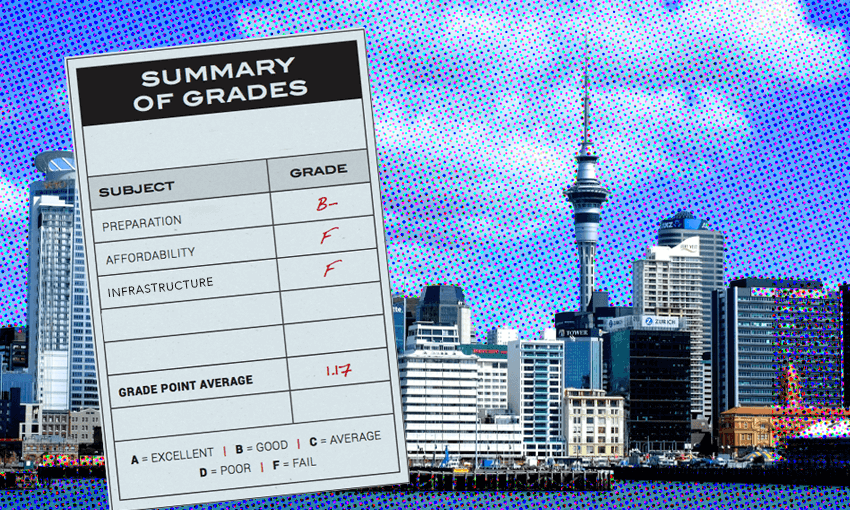

A report comparing Auckland’s performance against 10 other cities reveals familiar problems. Mayor Wayne Brown says it’s worthless. Duncan Greive disagrees.

Downtown Tāmaki Makaurau is where the big four multinational consultancies have set up shop, each with their name on a building, each attempting to win a corporate prestige measuring contest. EY is stumpy, but has the best playground, with Britomart at its front door. PWC’s is easily the tallest – but some (admittedly exceptional) gamers have the top floors, which takes the shine off a little. KPMG has bet on Wynyard Quarter – so far, so TBC on that.

Deloitte might have them all beat – it’s directly across from the grandeur of the downtown ferry building, with extraordinary 270 degree views of the Waitematā harbour. Which makes it the perfect aspirational backdrop to the release of a new report that aims to test the city’s performance against its peers, commissioned by the Committee for Auckland, in conjunction with Tātaki Auckland Unlimited and Deloitte itself.

Called “The State of the City”, the report was put together by the Business of Cities, a London-based consultancy, and runs to a hefty 77 pages. It tests Auckland against a prestigious peer group of mid-size global cities, comprising Austin, Brisbane, Copenhagen, Dublin, Fukuoka, Helsinki, Portland, Tel Aviv and Vancouver. To grade us, it draws on “more than 120 global city benchmark studies, which together span more than 750 comparative metrics”. Think about the other cities as our classmates – this is our report card.

From 20 storeys up, you’d think we’d ace the test. The raw materials are staggering – tangata whenua and super-diversity, the maunga, the twin harbours, those islands and beaches. Surely that should put us far ahead of Brisbane, Dublin or Austin? Looking out from Deloitte’s country headquarters, you might convince yourself that the report would be glowing.

It ain’t. The report is polite but stark. After some predictable platitudes lauding our diversity, geography and history, it lists off familiar issues around housing affordability, crime and transport, before finally making us sound like a really bad date. “Auckland currently lacks magnetism… Auckland is often viewed for its functionality more than its spirit and sparkle.”

It goes on to measure progress across 10 key areas, using a flower chart which maps progress or decline, and shows the average for all the cities within the study. Reproduced below, it’s an elegant way to display an ugly truth: this city is below average in half the categories, and more likely to be going backwards than making gains.

Worse still, the areas we’re overperforming in – culture, place and resilience – are those in which the city’s business and political leadership has little to do with. We’re sliding back in connectivity and prosperity, and anaemic in knowledge and innovation. Those pillars might sound overbroad, but they’re underpinned by problems we all recognise: “high cost of living, lower productivity and an increase in unemployment… Infrastructure deficits, slower progress towards decarbonisation and affordability and safety concerns.”

Talking about institutional failure over bagels

Paradoxically, the bad review gave the in-person presentation an enjoyable tension which elevated it from the self-congratulatory vibe that typically accompanies corporate breakfasts. The whole thing is driven by the good people at the Committee for Auckland, which says it exists “to lead the drive to fulfil the city of Auckland’s potential and find ways to deliver on the opportunity for our city and its citizens on the global stage”. It believes Auckland is “a fantastic city, full of potential”. The report says fantastic is highly debatable, and the potential largely unrealised. Awkward.

The committee, along with cosponsors Deloitte and the council’s tourism and economic development arm Tātaki Auckland Unlimited, invited around 150 people – CEOs, executives, policy types, consultants, many more comms people than journalists – to its unveiling.

As befitting a problem with many contributors, and a report with many funders, there were 10 different speaking roles across the hour, including mayor Wayne Brown, minister for Auckland Simeon Brown and the report’s lead author, Dr Tim Moonen, beaming in from London. He was unflinching (“the report holds the city up to a pretty harsh glare”) and brilliantly analytical – I could have happily listened to him for the whole hour. He also ran overtime, and had to be delicately cut off mid-sentence by Deloitte’s Auckland lead Kate Sutton.

She returned home from a role at the UN 18 months ago, the kind of smart, energetic person the city wants to grow and retain – but currently, eye-watering house prices and poor opportunities mean Auckland is a place talent can’t afford to live. It’s easy to make fun of events like this, but Sutton, like all the speakers, radiated a deep and sincere desire to figure this thing out.

The person most tangibly tasked with that is Mayor Brown, who Sutton introduced. He embodies the city in a way – stuck in his ways, narrow-minded, sometimes needlessly hostile, but also possessing an odd charisma and with potential to be great almost in spite of his clumsiness.

A case in point: he opened by dismissing the report we were all there to hear about as “a bit light on solutions” and “it doesn’t tell us a lot that we didn’t already know”. Mostly he used his speech as an opportunity to further advance his one man war against the limits of his role. Namely that local politicians have limited ability to impact the operations of Council Controlled Organisations (CCOs) like Auckland Unlimited, Auckland Transport and the development arm Eke Panuku. This is in fact by central government design, and he critiqued Rodney Hide and Steven Joyce for their roles in that.

Brown versus Brown

He also strongly implied that he was making good progress towards it changing. That’s why it was so fun that Simeon Brown was up next. His boyish no-relation namesake is minister for Auckland, and he delivered what was mostly a stump speech, much of which covered national issues – speed bumps, speed limits, crime. It could have been given in any city in the country and did not engage with the substantive issues of the report in any meaningful way.

It only caught fire a little when he obliquely but unmistakably dismissed the elder Brown’s contention that he was about to hand over the keys to the CCOs. The mayor and the minister say they like one another, and I believe them, but that battle – between central and local, between local and National, between Brown and Brown – is clearly not near over.

Simeon Brown did point out that the previous National government had commissioned a number of key pieces of transport infrastructure in the Waterview tunnel, the Vic Park tunnel and the City Rail Link. That last one is in many ways the city’s best and most plausible path out of its malaise – its opening will fix the central city and provide a natural place for huge residential development along the western and southern lines.

The rest of the speakers had less time and influence, but still managed some memorable lines. After Mayor Brown commented that his “management style is to keep up the floggings until morale improves”, Auckland Unlimited’s director of economic development Pam Ford got a zinger in response, noting that her organisation’s job is “slightly challenging when you’re being publicly flogged”.

A number followed the mayor in making bland comments around helping encourage tech and innovation, perpetually trotted out as a cure for city issues by politicians the world over. That prompted the line of the morning from chair of law firm MinterEllisonRuddWatts, Sarah Sinclair, who acidly dismissed the notion: “every city in the world’s got that idea”. Our next phase of growth requires much greater specificity about which industries we target. This would have the byproduct of giving us a sense of identity which, for all its challenges, Wellington has in spades.

A wero for the city

Sinclair’s speech was one of the shortest, but also the most persuasive. “No matter what the question, infrastructure is probably the answer,” she said. She’s on the board of the infrastructure commission, sure – but she made the case in language the leafy suburbs need to hear around upzoning and intensification. “I live in Westmere,” she said, “if I want a view that will never be obstructed, I’ll move to Kumeū.”

We need to be “really loud and public” with the tradeoffs, Sinclair said. The line about her home was a neat parable for the whole city. If Auckland is to beat its lethal cocktail of brutal housing costs, mediocre wages, average opportunities and slow, pricy transport, we must accept that what we’ve been doing isn’t working, and the city must change. Not just change in terms of how it looks, but in terms of how it approaches solving its most vexed issues.

This will require work from central and local government. Business and academia. Progressives and conservatives. Tauiwi and mana whenua. Consultancies and cultural institutions. Young and old. A whole bunch of communities and institutions, all ceding some ground to plausibly expect a different and durable outcome.

To know whether we’re succeeding, we need to have our homework marked with reports like the State of the City – even if they do only make concrete what we strongly suspect. So on that point, Wayne Brown, bloodyminded but right about some big and uncomfortable things, is wrong. Getting together over coffee and croissants at a fancy office to find out what we already know does matter. Because next year we’ll have our homework marked again. And no one in the room could stomach another report like this.