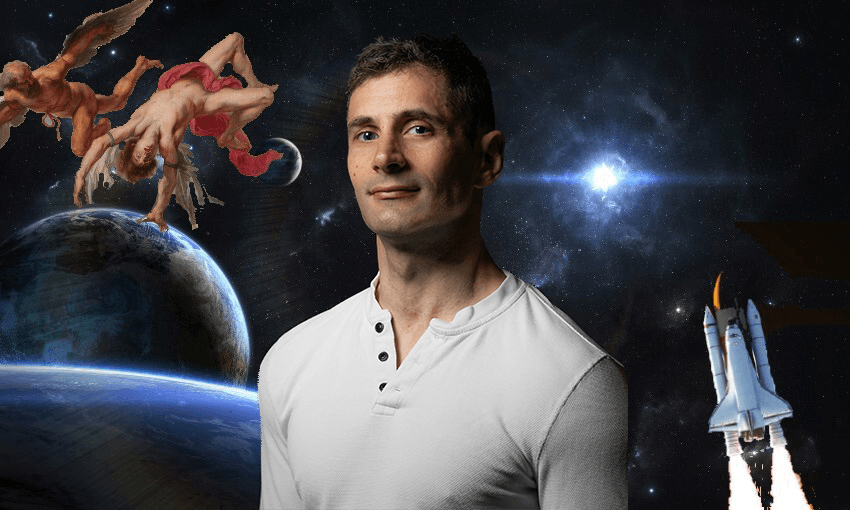

The ex-military, gay, Lamborghini-driving CEO of Rocketwerkz is one of the highest profile figures in New Zealand gaming. Michael Andrew went to the new Auckland office to meet the man known as “rocket”.

“It’s the fastest lift in the country,” said Rocketwerkz’s chief operating officer Stephen Knightly before we shot to the top of the new PWC building at eight metres a second. I’d heard about the elevator, but I couldn’t quite prepare for the way my ears popped, nor the sickly way central Auckland’s streets immediately vanished from sight through the floor to ceiling windows. In an instant, however, we came to a stop at the 39th floor – the highest office space in New Zealand.

The doors opened onto the “lobby” – a luminous black and green neon lit room filled with techno music that reminded me of an arcade or laser strike arena. Around the corner, a pair of glass doors silkily parted into an ivory-coloured “airlock”. Beyond that was the main office area, and that spectacular view of Auckland – humbled and hunkered far below.

Knightly, obviously used to bringing incredulous visitors through this bizarre portal, seemed amused at the strange smile that I couldn’t seem to subdue. He began taking me through the rest of the place, but I’d already seen enough to draw my own conclusions – this was not a normal business.

This was no major finance or law firm, or even a modern IT company. This was a six-year-old Dunedin gaming studio that, with the financial backing of a Chinese gaming behemoth, had annexed the highest and most prestigious piece of office real estate in New Zealand from the corporate heavyweights that would typically lay claim to it. The coup had been impudently commemorated by the sci-fi fit out in the lobby – a $5m signal to the business world that the prosaic conventions of old did not apply here.

Knightly showed me more: the staff working at their elaborate multi-screened desks on the big new game Icarus, the weird metal screens blocking them from the windows and the sun’s glare. Every aspect seemed to add to the unorthodox. The only thing that seemed to be normal was Knightly – the measured COO, playing the affable host and watching me carefully.

Then Dean Hall emerged, and any lingering sense of convention went out the window. I’d read about Hall beforehand: his military career, his summit of Mt Everest, the millions he’d made making games in Prague in his early 30s. His Instagram account depicted something of a sybaritic playboy, with multiple photos of his Lamborghini Aventador – which he said he purchased through text – and even more of him showing off his muscle-bound torso. When he showed up for our interview wearing a green t-shirt, yellow stubbies, pink socks and white shoes, it was undeniable he did not adhere to the customs of a CEO.

Greeting me with a sanitary fist bump, he said his team had just celebrated a significant milestone with Icarus – Rocketwerkz’s biggest and most hyped project to date and developed with the financial backing of the Chinese gaming giant Tencent – the largest gaming company in the world, which owns a 45% share in Rocketwerkz. After some small talk, the three of us walked through the main office and upstairs to an executive lounge reserved for management. There Hall told his story.

Early years

He was born in Oamaru in 1981 to a white, middle-class family. He became interested in gaming and computers early, playing his cousin’s Commodore-64 so much in one sitting he vomited. Later, his parents bought an Amiga 500 at considerable expense, and it was on this that Hall learned how to write basic.

“That was the first computer I learned to peek and poke, and being able to write directly to the graphics buffer. I think at that point I was hooked,” he said.

Attending Waitaki Boys High School, at 16 he applied for the Royal New Zealand Air Force’s new undergraduate scheme, which funded him to study a degree at Otago University at age 17. After he graduated, he did his first spell of work experience at Whenuapai airbase in Auckland as an officer cadet, eventually becoming a commissioned officer and attaining the rank of Lieutenant.

“I guess as a teenager, it gave me a clear vision of something to do – you get given a value system; you get given goals. Even down to the little trinkets and medals you wear – you get rewarded for things. It’s like a board game; putting little tokens on the board.”

Hall said he topped his officer training and was awarded the Graduate Who Shows the Most Potential and Best All Round Graduate – the first time a ground graduate received both awards in RNZAF history. While he said he gained a lot of discipline and focus from the armed forces, his tendency to challenge what he perceived as inefficient or out-dated systems caused some consternation with his superiors.

“I was quite opinionated,” he said. “I almost got in trouble quite a lot for having strong opinions that were maybe counter to the general thinking. I think I nearly got court-martialed a couple of times.”

After leaving the RNZAF in the mid 2000s and working as a video game producer in Wellington, he enlisted in the army at 27 and began his second round of officer training in the Royal New Zealand Corps of Signals. He described a navigation exercise at Waiouru Military Camp, in which he collected publicly available geographic data, and wrote it into a programme that allowed him to complete the course in record time.

“I took satellite and height map data and fed it into this little visual model I’d made of the terrain, and I made a simulation of the wire. And then I just put the points in and I took photos. So instead of navigating with a compass and doing bearings, I just made a little flip book.

“They got kind of mad because they were like, ‘you didn’t get it. You broke the rules.’ But I realised I hadn’t broken the rules, I just made a new way of doing it.”

As he talked, he couldn’t seem to sit still – and I don’t think he wanted to. He often fidgeted with his socks, digging his fingers into his ankles as if they were itchy. At one point his gaze drifted behind me to the kitchen area, where he had become distracted by a strip of panelling that had come loose from the wall. He pointed it out to Knightly, who seemed to make a mental note, before returning to observe the interview.

Knightly stayed quiet throughout most of the conversation, but he did interject whenever we touched on a certain topic – such as employee redundancies, or the (undisclosed) cost of the lease of the new Auckland office. The COO had been at the company only 14 months – after spending a decade as managing director of gaming company InGame – but based on his heavy media presence, he had taken on an instrumental role managing the communications and brand of Rocketwerkz, and steadying the ship.

Meanwhile, Hall continued chronicling his army days, and the pivotal point that saw him transform into a millionaire.

Day Z

He’d been posted to the Singapore Armed Forces on an exchange programme, and was dropped into Brunei on a jungle training exercise. The mental and physical toll was so severe that he lost 25kg and had to later have bowel surgery. However, amid the suffering he had something of an epiphany, in which he realised that anything he wanted in life was within his grasp.

“What I was doing was really hard, and was physically hurting me and was very distressing. But then there was kind of like this switch when I realised that being happy was a decision that I could make.”

“I decided I was just going to enjoy the next 20 minutes, and I think at that moment I realised that maybe the answer to all my problems was me just deciding things. I decided that I was going to make games and make a game studio. I just decided I was going to do those things.”

His struggle for survival also served as the inspiration for the project that would propel him to success and wealth. After recovering from his ordeal in hospital, he took advantage of a leave of absence to work on a contract with Bohemia Interactive in the Czech Republic, where he produced Day Z – a PC mod (modification) in which the player has to survive a zombie apocalypse.

The game was a global hit, attracting one million unique users two months after its release, and, Hall said, earning him his first royalty cheque of USD$5m. He stayed on with Bohemia to work on a standalone version of the game, but, after completing a life-long dream to summit Mt Everest in 2013, made the decision to return to Dunedin and set up Rocketwerkz.

‘Dumpster fire’

While Hall’s ambition was to set up a gaming “valve in the South Pacific”, he initially based himself in London to work on Ion, his next project, while his sister Stephanie took over day-to-day operations of the newly created Rocketwerkz in Dunedin.

According to media reports, Hall’s sister managed the administration duties of the young company admirably, helping it expand from three employees to 45 over three years.

One former employee I spoke to was effusive in assessing Stephanie Hall’s leadership.

“She ran Rocketwerkz single-handedly – not knowing anything about business – for the best part of half-a-year before Dean showed up,” said the former employee. “She did all the paperwork for getting visas or getting visa approved employee status. So I have no end of praise for her. I think she’s incredible. She’s quite a different person to her brother.”

However Dean Hall described those early years and his time in London as a “dumpster fire”.

“The London experience did not work out,” he said. “I think I wasn’t controlling things and I think if you look at the teething troubles we had in Dunedin, my original plan was just to live my life and give a bunch of people money to make stuff, but it didn’t work.”

“So, you know, originally it was supposed to be the opposite of the Dean Hall show, but then it ended up that the Dean Hall show was what worked.”

Rocketwerkz became known as an experiment – a modern, technology-heavy company, based in a small city, yet implementing Silicon Valley-type employee benefits. The traditional hierarchy was scrapped, and an equitable pay scheme – in which Hall’s salary was capped at 10% higher than the next senior employee – was implemented, along with unlimited annual leave – although this was later restricted to senior staff.

Despite the unique perks and its rapid expansion, Rocketwerkz initially struggled to find its stride, and several projects – including the highly anticipated Ion – never came to fruition. Hall said it wasn’t until the last two years that the “dumpster fire” was finally extinguished and things started to click into place.

“I was just going from one disaster after another. But doing anything worthwhile is really tough.”

“I think if you look at the growth of Rocketwerkz, we were trying to say, ‘OK, we tried this thing, it didn’t work. What should we do now?’”

Despite its unprofitability and the project cancellations, the studio’s rapid expansion and ambitions didn’t go unnoticed, and in 2016 Tencent bought a 25% stake. With the new investment, Rocketwerkz did deliver a successful project in 2017: Stationeers, another problem-solving, survival game, which was inspired by cult classic Space Station 13.

“I think for us it ended up becoming a really cool success story,” Hall said. “We cancelled this big huge sort of boondoggle project and anything that wasn’t working, and we refocused the team around this little project that was doing pretty well.”

Dunedin

So what exactly didn’t work during Rocketwerkz’s Dunedin years? In the media, Hall took aim at New Zealand’s slow broadband and immigration bureaucracy as the partial reason for his company’s woes.

However, the former employee I spoke with said the issues at Rocketwerkz Dunedin stemmed from unsatisfactory management, and Hall’s initial absence. Although the employee was initially impressed by the employee benefits and company structure, they were far more complicated to implement in practice.

“We had a team here in Dunedin, working mostly without Dean’s input, but we were trying to get his input all the time, and never getting anything useful out of him,” the former employee said.

Because Hall had abolished the traditional management hierarchy, the former employee said project teams were expected to make decisions at their discretion, but lacked the authority to complete tasks. “A lot of people would describe being ‘Deaned’, which was like when Dean would come in and would basically just up-end all your code and your projects, because he didn’t like it.”

Hall’s management style comes in for sharp criticism on Rocketwerkz’s page on company review site Glassdoor, where people claiming to be former employees of the Dunedin studio lambast Hall’s character and the company culture. In response, Rocketwerkz’s Knightly called the claims – including those of the former employee I spoke with – “unsubstantiated”, noting that because the comments were anonymous it was impossible to respond or address the criticisms directly.

In any case, the negative comments were offset by a fleet of glowing reviews, most of which were posted in the past year from current employees based at the Auckland office.

These mostly praised the talented and experienced team, the flexible schedule, and the leadership, which gave them “well defined goals and responsibilities with enough freedom to give us agency in our work”.

When I asked Hall about his leadership, he was very candid about his shortcomings, describing himself as a better operator in a crisis, and his “vision” as his best quality.

“When things aren’t difficult, I’m actually not great at leading, but that’s where we’ve kind of got that set up well. When things are going on normally, people might not see me that much.

“We give people a lot of freedom at the senior level, but we also demand a lot of responsibility from them and hold them accountable, and people will get exited if they don’t live to that standard.”

Covid-19

This philosophy was put into practice early in 2020, when 20 staff were let go from the Dunedin studio after the game they were working on was cancelled. Hall said the decision came to him while on a flight to Dunedin, at the same time he got the idea for Icarus. He decided that the lack of progress and profit in Dunedin was unacceptable, and he wanted to steer the company in a new direction.

The decision resulted in a backlash from those involved, who argued it was unwarranted, especially since Rocketwerkz had claimed a $414,746 Covid-19 wage subsidy. Knightly immediately challenged the social media claims, saying that the decision to make staff redundant was taken before any wage subsidy was applied for.

While some of those employees who lost their jobs were rehired, Hall told me the initial restructure was the hardest decision he ever had to make. However, he maintained that it was justified.

“The classic thing is that I’m like $8m deep in the company. It’s a long time before I’m going to get my money back.

“I’m OK with failing stuff myself, but going and telling other people they’ve failed sucks. Some of what we were doing in Dunedin was not working. And we were just going nowhere with it.”

Knightly chimed in here, offering a more subtler perspective: “That’s to clarify that the project failed. The people themselves might have been doing great quality work and working hard, but there was a project failure.”

As for the wage subsidy, Hall said it was a critical move to ensure the future of the company.

“Without this wage subsidy, I don’t think we would have been able to keep the Dunedin studio. Without a doubt.”

Auckland

Despite having a Tesla S P100D and property in Dunedin, Hall said he seldom visits anymore. His family are no longer in the business, and he’s firmly settled in Auckland, living at a waterfront apartment a short walk away from the new office.

But is the Auckland studio plagued by the same woes as the Dunedin one? Are employees still being “Deaned”? It doesn’t seem like it. In any case, Hall said he’s learned from the past and is taking a more hands off approach to Icarus’ development.

“I know and understand every single part of it, but I shouldn’t work directly on it. That was something I learned only quite recently; I used to be able to distract myself if I was having a bad day; going and coding directly on the game, but you lose a level of perspective doing that.

“This project really is the first time I don’t have the game installed in terms of the project files. To be able to enact change in the game I have to go communicate with someone. And I think that’s been working really well.”

With the global video game industry worth USD$156b and forecast to grow, there’s clearly a lot riding on Icarus’ success. It’s also being developed at a time when New Zealand’s domestic gaming industry is flourishing, with export earnings rising 60% in the last year due to global audiences being locked down and at home.

With Rocketwerkz the perfect paragon of that growth, I asked Hall if he’s proud of his accomplishments, especially when he looks around at his new studio at the top of a $500m building.

“No,” he said emphatically. “I just look around and I see the bits falling off. I hate the grading down there [in the office], I think it should all be open.”

“I long ago learned I’m not motivated by the stuff I have. It’s just a car. It’s just a building. I couldn’t give a shit about the office, to be honest – whoop-de-doo. The lifts are fast, I like that. But I’m way more excited about the quality of the project that we’re doing. For me, it feels like my best work.”

He was clearly happy with Knightly too, whom he credited during our interview as a critical asset. With the COO managing the day-to-day operations, Hall was free to dream up ideas, and perhaps even enjoy some more downtime creativity; he mentioned he was working on a small “train game” and had an impressive Lego collection in his office.

According to the former employee, under the new management regime the Auckland office appears to be much more cohesive than the Dunedin one.

“I’m not there, so I’m not seeing how it’s running. But my feeling is that if people can actually manage the place, and sideline Dean, then it might have some chance of success.”

Outside work

While Hall’s reputation in the workplace varies depending on who you talk to, outside of Rocketwerkz he seems far less complicated. He attends the gym everyday, his favourite places in New Zealand are Wanaka and Queenstown, and he’s at his happiest when he’s exploring. His summit of Mount Everest and his ownership of a $600,000 Lamborghini were both things he fantasised about as a teenager, he told me. His wealth now means he’s free to enjoy and pursue those youthful dreams whenever he wants.

Was there anything he felt like he couldn’t do? I asked him

He dug his fingers into his socks. “Relationships,” he said.

“I think I want a lot more out of life than a lot of other people do. But if you want to live like that, you have to deal with brutal honesty about yourself and there’s zero room for making excuses. That means I end up judging people quite heavily.”

However, director of Auckland Pride Festival Max Tweedie, who knows Hall socially, said he’s never seen a negative side of him.

“He’s a real good guy. He’s always felt honest and authentic.”

Tweedie said Hall first approached him last year asking how he could support Auckland’s rainbow community. Tweedie was impressed with his integrity, and the way he was determined to follow through straight away with what he said. Rocketwerkz has since become a major sponsor of Auckland Pride Festival.

“There’s very few gay CEOs in the country. And so I think as one of them, he felt he had a bit of a responsibility,” Tweedie said.

Despite being a rarity in the CEO world, Hall said he’s never let being gay define his reputation or career. Coming out at 17 was not a big deal, nor was his time in the air force, where he said he might have been the first openly gay officer.

“It didn’t really cause many issues because I just focused on being better than everyone else. It was the same in the army, people didn’t really care because I was beating them in fitness tests and I wasn’t causing any problems.

“I never wanted to be known as a gay video game designer – I wanted to be known as a game designer.”

He lamented the enduring stigma that made it hard for young people to embrace their identity and sexual orientation, and said that was the main reason for supporting Pride.

Icarus

I realised I had gone over time and quickly wrapped up the interview. Hall bounded off to continue his day with that phenomenal, childlike energy, while Knightly escorted me out.

As I left the building and walked along Customs Street, I realised I hadn’t asked much about the big new project Icarus; when it was coming to fruition, or how it had got its name. Looking back up at that monstrous building, I couldn’t quite resist thinking that the game, that audacious studio in the sky – and the man who runs it – was all somehow inspired by the real myth of Icarus – the proud, eager youth who burned the wax in his wings and fell from the sky after flying too close to the sun.

While the myth serves as a warning of the perils of excessive ambition, I doubt Dean Hall ever worries about flying too high and burning his wings.

After all, it will take a lot more than that to bring him back down to earth.