Sam Brooks heads along to Meatstock 2020, and finds himself questioning the symbiotic relationship between meat-eating and machismo.

As I entered Auckland’s ASB Showgrounds for the first day of Meatstock 2020, a girl was exiting. Trucker cap on, eyes hidden behind aviators, manicured fingers wrapped around a can, itself wrapped in a chilled cozy. One of the security guards hollered, “Ma’am!” and beckoned with two fingers. The one finger beckon? Fine. Two fingers? You’re not coming back in to get your second (or fourth) Woodstock.

“What’s in that can?”

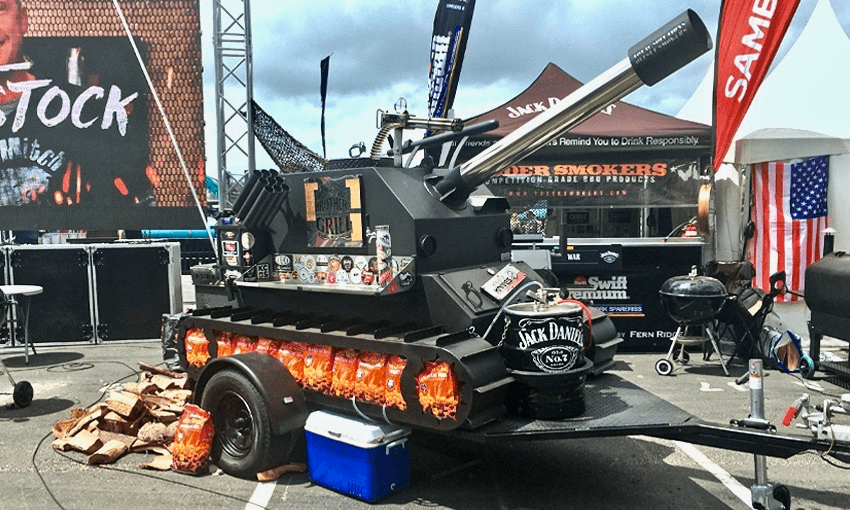

A rhetorical question. She knew. Jack Daniels signs are everywhere; there’s enough Jack Daniels to cater a biker’s funeral. The girl rolled her eyes. She tossed her cozy-can back because, of course, she wasn’t allowed to take it out of the grounds. The security guard shook her head and chuckled.

The other security guard present nodded, either in appreciation or resignation. “You scull, girl.”

Meatstock is more than the name suggests. You read that and you think it’s a meat and perhaps music festival. And yes, it is that. There are food stalls (almost exclusively selling meat) galore. There is music: Katchafire, Sola Rosa, and a band called Cookin’ on 3 Burners, which is a band name about as on the nose as oil flying from the pan. There’s an area in the grandstand where you can watch demonstrations from some of the best barbecuers in the world.

But it’s much more than that. It’s an expo of all things meat, and largely barbecue, related. Even more crucially? It’s an expo celebrating all things masculine. There are stalls upon stalls of barbecue equipment. There is a barber competition, there is a beard/mo/mullet competition, there is a “Pork Rib Throwdown”. While meat is in the name, masculinity is in the air.

And now we have to address the dead cow in the room: meat is highly unpopular in 2020, and rightly so. Animal agriculture is one of the biggest contributors to climate change, and science shows we should be eating much less meat than we currently are if catastrophe is to be avoided. It’s also the industry that is the most vivid representation of capitalist consumerism: you farm something specifically to be killed, en masse, solely to consume it. The cycle repeats until you can’t repeat it. No matter how ethically you think about it, it’s ending the life of something else to sustain your own.

Now, a quick confession and clarification. I eat meat. I won’t call it a necessity in my life, but it’s something I’ve done my whole life, and I often wrestle with the ethics of it. I attend the festival not as an enthusiastic meat eater, but as someone who regularly eats it. I also attended as someone who sits on the spectrum of masculinity somewhere between present-day Grant Robertson and your average Western Springs swan. I might not be the yardstick by which to measure masculinity, but I’m a pretty savvy judge of it.

A lot of easy assumptions can be made about Meatstock, and my first hour wandering around the festival seemed to meet (ha) them. There are more black clothes than a Marilyn Manson concert. The ratio of men to women is pretty comfortably 70-30. Jack Daniels is the staple, beer is the alternative. The one vegan food stand (Sunfed Foods) is attracting people through strategic use of free samples, likely knowing they’re not going to convince the die-hards, but perhaps intrigue a few fence-sitters. (Consider me convinced. Their chicken might not feel or taste exactly like chicken, but it’s close enough that I’d willingly eat it just to feel a bit better about myself.)

My friend and I wandered around the festival and fit in fairly seamlessly, even with me in my Tegan & Sara T-shirt and denim shorts. He got some brisket on fries, I got a beautiful pulled-pork burger that split the difference between smashable and spicy in exactly the way a festival burger should. Then we walked into the beard and mo competition (with a mullet competition as a cheery coda), and take on the whole festival changed.

The theatre of it was incredible – it was literally just men applauding other men’s facial hair. There were beards you wouldn’t expect to see outside of a casting call for Lord of the Rings dwarves or your average Nordic heavy metal band. Moustaches that French chefs would doff their toque blanche hats to. And finally, mullets. Oh, the mullets. Never have I seen so many mullets displayed, and strutted, with the same joy and confidence as on RuPaul’s Drag Race runway.

It was as wholesome as a well-cooked meatloaf. Anywhere else, these men might be mocked. I might be doing the mocking, frankly. But these men got to strut their stuff, in this case the hair upon their head, and feel pride in it. All power to them. I got to hear a man say, in earnest, “Barbecue’s a sense of community and beard is a big part of it.” (In the audience, a few supporters had a shirt with this quote on it, courtesy of Kerikeri barbecue supply store Barbecue Boi.)

If we all took this much joy in what we did every day, the world would be a much more pleasant place. Nowhere else am I likely to see a man say the words: “I wanna thank my wife for letting me grow this mullet.” The host called out to the wife in question for confirmation, who gave an enthusiastic, smiling thumbs up.

I ended my first day at the first round of Butcher Wars, which is ripe for being turned into a reality show, commissioners take note. Four butchers are given two cuts of meat – one pork, one lamb – and 30 minutes to cut and present it the best way they can. The butchers are ranked on speed, creativity, technique (so knife/blade/saw-work) and presentation.

It’s easy to forget that they’re cutting meat. You turn off from the fact they’re slicing into dead animals, much as you might do when you’re eating those dead animals. It’s like watching any competent craftsman at work; you can relax in the knowledge that even if you’re not the one in good hands (RIP, animals); you trust that they know what they’re doing. Blades flash, hands fly across their workstation, garnishes are placed with all the speed and grace as a Royal Ballet dancer.

At the end of the first round, the youngest competitor gleefully expressed his delight at coming to New Zealand for the first time, and to have the opportunity to show off his stuff. Another made candy shop meat – complete with meat lollipops and pork sweets. Another made a beautifully detailed spread that looked like it would be at home at any Remuera luncheon, dutifully thanked the sponsors, and ended with a call: “Let’s make butchery better than chefs.” Assume a [sic] there.

The fourth presented his showing with glee. “I get attacked by vegans all the time. So I’ve got meat that tastes like meat but looks like a plant.” His competing piece? A beautiful, surprisingly delicate array of pork sushi and garnishes that did, indeed, look like a plant made of meat.

A few days before Meatstock began in earnest, I caught two trains to attend a barbecue masterclass. Even the idea of doing it seemed farcical to me, a bit of a laugh. I’ve barely turned on a barbecue, so I’m hardly qualified to attend a beginner’s class, let alone a masterclass with Big Moe Cason, a boisterous African-American man from Iowa.

When I roll up to the Blue Ox Babe BBQ in Pukekohe, I find myself in the largest group of men since I’d attended a men-only networking lunch. There are maybe five women in attendance, including those working the masterclass, and many of them appear to be plus ones.

A bunch of us stand outside nervously. Some hold folders, some nervously clutch rolled up printouts of the notes Big Moe had sent us to read beforehand. Before we are let in, like cattle into a pen, Big Moe has been prepping his station while smoking a cigar, sunglasses and apron securely on.

When the masterclass starts, Big Moe is as affable and knowledgeable as you expect someone who dubs himself Big Moe to be. He knows his shit, meat-wise, and even more so when it comes to barbecue. I take dutiful notes, on the off-chance that I might at some stage be expected to man (ha) a barbecue. I know now that you season pork an hour before, not the night before. You remove membrane on a pork rib, not a beef rib. Most crucially, and helpfully for a novice like me, if pork smells funky when you remove it from the package, step far away.

Through the masterclass, I start to look at Big Moe Cason as some platonic ideal of masculinity. He’s a steady, gentle, guiding hand. Even when some of the masterclass participants briefly take the chance to show off, proof that statement-as-question is not just the realm of writers’ festivals, Big Moe calmly replies to them and continues his masterclass. Even when someone says, without context, raising his hand a single split second before talking, uncalled upon: “What about wild pork?”

Big Moe stops the class, answers the question with the kind of detailed intelligence that comes from experience – wild pork is lean and unreliable, often, whereas the well-fed pork you buy in stores is more reliably fatty – and returns to the class at hand. He reminds us that if we’re cooking for friends and family, we can ignore some things he’s saying, but if we’re cooking for competition, as charitably maybe half of these participants would be, then listen to what he has to say.

While he teaches us, he’s surrounded by heavily branded merchandise. Any chance to sell merch, after all. When I sometimes zoned out, because I’m about as likely to step towards a fire pit as I am towards a chia seed salad, I thought about the link between meat and masculinity. Namely, that it’s all in the marketing.

There is nothing inherently masculine or male about meat, just as there’s nothing inherently feminine or female about salads. But still, if you’re a dude out at a restaurant with a lady, you’re more likely to get the steak set before you by a rushed member of the wait staff than the salad. We’re told constantly, through ads, through society, that meat is for men. If you know what you’re doing at the barbecue, you can rest easy. If you can cook a side of steak better than that guy, then you’re more of a man. And if you can cut up the pig at the table in front of the nuclear family, then you’re the very image of the man that every ad you’ve watched your entire life has told you that you need to be.

There’s nothing easier to market to than someone’s insecurity. Question someone’s masculinity, say you can fix it with the right knife, the right barbecue and the right cut of meat cooked exactly right, and here’s the exact cost of all of that, and someone’s insecurity will answer it with their wallet.

As much as it is a chance to give genuinely great barbecue tips, the masterclass is another opportunity to sell. And if you’ve been told all your life that the way to be a better man is to barbecue a bit better, why wouldn’t you spend $245 (including lunch) for the opportunity, especially when you have the chance to spend it with likeminded people? Swap out a few of the nouns, and there’s nothing different here to a wellness seminar where the lecturer is selling their book for a marked-up $50 at the end.

Towards the end of the masterclass, a man at my table exclaimed: “The most you can expect is 10 good tips – who can remember all of this?”

Across the bar, a woman continued to take detailed notes.

‘Tell me out there, people at home. Who would love a soft cock?”

With this exclamation from the host of Butcher Wars, my second day of Meatstock began. I’ve no idea what a soft cock is in this context, but I suspect it’s one of many words that have a different context inside the grounds of Meatstock than they do outside. (See also: poppers.)

Across the way, barbecue legend Diva Q mouthed “Wow!” as she waited to start her demonstration on how to easily spatchcock a chicken. Her tips, in short: butter. Lots of butter. There was a near-perverse joy in watching her crack open a chicken and gleefully say, Southern accent wielded like a stringed instrument, “Crunch a few bones and you’re gonna have a better day.”

After watching Diva Q serve up her spatchcocked chicken, along with a plug for Traeger Grills, I went inside to catch another round of Butcher Wars, featuring a German legend, a Geelong stalwart and a Pukekohe-based butcher who had only been doing it for six months. This last contestant had a supporter in the second row, yelling his support loudly and enthusiastically throughout the half hour. “Let’s go, Poncho!” It was clearly the kind of male friendship that would make even the staunchest bloke shed a hoppy tear.

The stage felt like the great equaliser here. No matter their barbecue-god status back home, on that stage they just had to make the best out of the lamb and pork they’d be given. It’s stressed, throughout, that all the meat used goes to food rescue charity KiwiHarvest.

That might jar a little bit with the next event: the Meatstock Pork Rib Throwdown. Competitive eating is the most visual and literal representation of over-consumption there is. People came from across the country and even from Australia to compete in the Meatstock event, including New Zealand’s top-ranked competitive eater Nela Zisser. The stage is set, the meat is laid down, the spewbuckets are in place. Now they’ve got three minutes to eat as much meat as possible.

Once the contest starts, it’s absolute chaos. People are shoving meat in their mouths, swallowing water, jumping up and down to get the food down faster. There’s a rule that you can chipmunk, which means you can shove as much food in your mouth before the clock runs out, and then you get 60 seconds to chew what’s left and swallow it. In a bizarre way, the Throwdown is the most egalitarian event of the entire day. Whether you’re a man or a woman, you have no advantage. It’s all about how much you can eat (and how much you’ve trained to be able to increase your stomach capacity). The only difference is that men are introduced along with their weight, and women are introduced with their height. You can draw your own conclusions on that one.

As the judging happens, a man next to me scoffs to the people sitting around him. “They’ve only eaten 400 grams!” Wherever you can watch a professional doing the thing they’ve trained their whole life to do, you can find a man in the audience saying to his neighbour that he can do it better. (The man in question later competed in the amateur Pork Rib Throwdown. He tied for second.)

When I walk out of Meatstock 2020, I stop by the Sunfed stall again. I have a bit more plant-based chicken. It’s good, better than I remember from yesterday. It even compares to the chicken taco I had from Miss Moonshine’s earlier in the day. I looked around the rest of the warehouse – a display of classic cars here, a barbershop stall there, Jack Daniels as far as the eye could see. None of it is explicitly just for men, but gender is a construct made up of a whole bunch of different things, after all. Put all the individual parts of Meatstock together and you’ve got a ready-made kit for how to be a man’s man, filled with masculinity from boot to beard. If you can pay the right price, that is.

Sunfed proves that you might be able to take the meat out of meat, but I’m not sure if you could ever take the man out of meat.