Twenty years ago, Metal Gear Solid 2 predicted a world that was both more ridiculous and less bleak than the one we live in today, writes Sam Brooks.

Warning: Contains major spoilers for a very old game.

Earlier this week Japanese video game maker Konami made a shock announcement. Metal Gear Solid 2 (along with its sequel-prequel Metal Gear Solid 3) would be delisted from online storefronts on November 18 – just days after its 20th anniversary – with the company citing issues emerging from “historical archival footage used in-game”. The announcement was something of an ironic coda to a visionary video game that explored ideas around inheritance, truth and clarity at the dawn of a digital apocalypse.

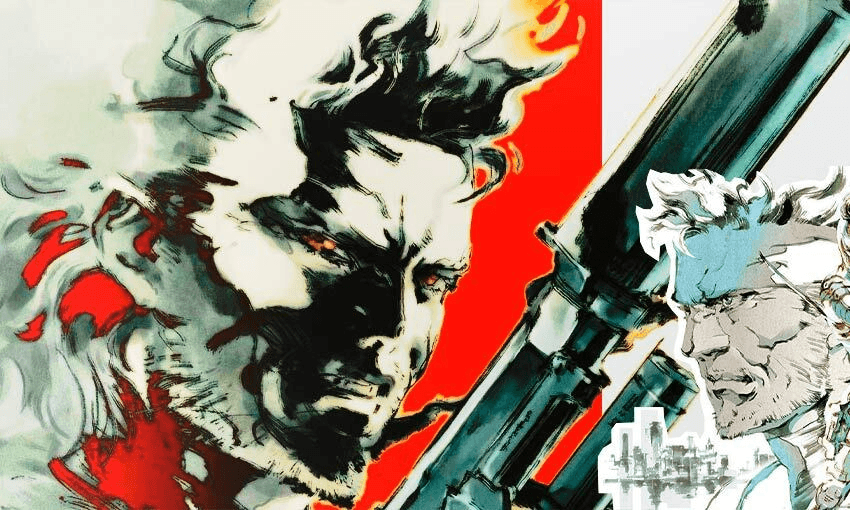

Metal Gear Solid 2 was revolutionary for a lot of reasons. While it wasn’t the first postmodern game, its launch was definitely the first time a highly anticipated, triple-A title embraced postmodernism so fully. Many essays have been written about how it messed with audience expectations and how it pushed the limits of what gaming could do.

That’s not what sticks with me, though. Instead, what amazes me most about the game, created by the once-in-a-lifetime visionary Hideo Kojima, is how accurately it predicted the future. Way back in 2001, when the concept of social media was basically a twinkle in some Harvard sociopath’s eye, Kojima showed us how we would engage with each other, and with the internet. That moment of prescience doesn’t come until the very end of the game, though, so you’ll need a little bit of set up first.

A precis of the Metal Gear Solid 2 plot reads like it could have been ripped from a Tom Clancy novel: a spy has to investigate a terrorist cell holding the president hostage, only to find out that things are much complicated than they seem. In reality, the story is a whole lot weirder: it turns out that the whole mission has been arranged by a series of AIs in order to replicate the events of the first game as closely as possible, to prove that experiences and information can be imprinted on a person to reproduce. (Don’t worry about understanding that, millions of people who have played it right through are still no wiser than you are.)

As Raiden, the game’s surprise protagonist, discovers all this he also realises the mission control that has been guiding him all along – grouchy military guy Colonel Campbell and Raiden’s boundary-less girlfriend Rose – are those very AIs. They go off the rails in a terrifying sequence that involves asking the player to turn off their game and also the Colonel ranting nonsense like “I need scissors61!” in a way that honestly seems tame compared to most Facebook comment sections today. The big revelation, though, happens in an hour-long cutscene where the duo explain their motivations. Yeah, there’s a reason why people weren’t a huge fan of this at the time….

The relevant part is helpfully excerpted in this tweet below:

What's a video game moment that lives in your head rent free?

Here's mine: pic.twitter.com/rKEwivVC8F

— Blessing Adeoye Jr. (@BlessingJr) January 26, 2021

Their motivations are, in short, to create a version of the internet where all the trivial stuff is filtered out from the “truth” so human society doesn’t regress in the then-new social media era.

Essentially, they’re advocating for a form of censorship: they want to restrict memetic developments, and memes. When I say memes, I don’t mean a silly image you share with the group chat, I mean the academic definition of a “unit of information” or a “fact, an opinion, or an ethic that is inherited by future generations” – think genes, but for information. The big difference here is that genetic selection is amoral, whereas memetic selection is moral. Still with me? Great (and look, there’s a reason why this game is used to teach meme theory in universities, this is way more fun than The Meme Machine).

Take this line from the fairly spooky rant excerpted above:

“In the current digital world, trivial information is accumulating every second, preserved in all its triteness … Rumours about petty issues, misinterpretation, slander. All this junk data preserved in an unfiltered state, growing at an alarming rate.”

Now, for contrast, take this quote from a Wired piece from 2015 titled ‘Facebook’s Echo Chamber Isn’t Facebook’s Fault, Says Facebook’:

“Researchers found that users’ network of friends and the stories they see do reflect their ideological preferences. But the study found that people were still exposed to differing points of view … a user’s click behaviour—their personal choices—results in 6 percent less exposure to diverse content for liberals and 17 percent less exposure to diverse content for conservatives.”

To further illustrate, here’s another line from the spooky rant:

“The untested truths spun by different interests continue to churn and accumulate in the sandbox of political correctness and value systems. Everyone withdraws into their own small gated community, afraid of a larger forum. They stay inside their little ponds, leaking whatever ‘truth’ suits them into the growing cesspool of society at large.”

And an excerpt from last month’s Genesis-level flood of leaked Facebook information via NiemanLab:

“The company’s data scientists confirmed in 2019 that posts that sparked angry reaction emoji were disproportionately likely to include misinformation, toxicity and low-quality news … That means Facebook for three years systematically amped up some of the worst of its platform, making it more prominent in users’ feeds and spreading it to a much wider audience.”

Perhaps the bleakest thing about all this is that the dystopic AI of Metal Gear Solid 2 is actually less cartoonishly evil than the real world algorithm that followed it. The fictional AI intends to “wade through the sea of garbage you people produce, retrieve valuable truths and interpret their meaning for later generations”. The real life algorithm takes your racist uncle and amplifies his thoughts on the vaccine, even though his epidemiology skills barely qualify him to trace his stomach ache back to that bad chicken he ate.

Twenty years on, the cruel irony of this game being removed from storefronts, even temporarily, speaks to its strange prescience. But that’s only the half of it. Though Hideo Kojima tried to imagine the darkest, most ridiculous endpoint of communication in the digital age, he didn’t go anywhere near far enough. Give me his dystopia over mine, any day.