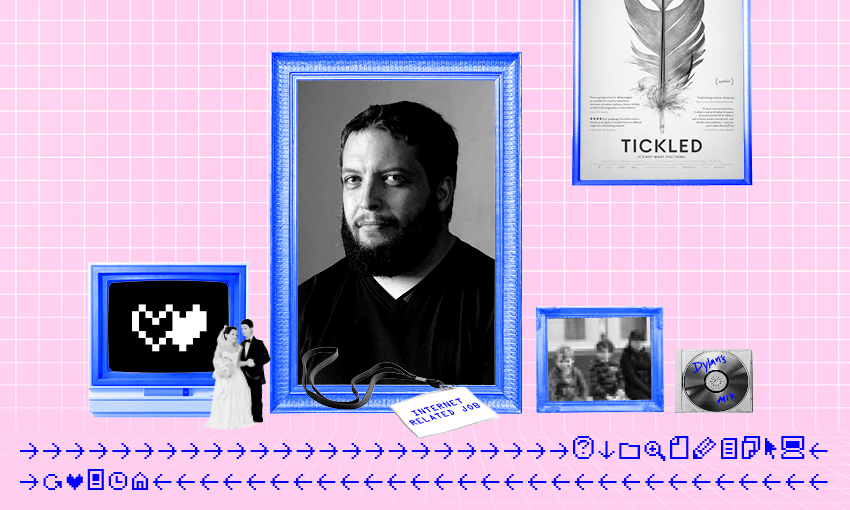

For IRL, Dylan Reeve spends all day writing about how the internet impacts other people’s lives, but he’s never turned the spotlight on his own life before. Until now.

Since September, it’s been my job to write about the ways the internet intersects with our real lives, but I’ve never taken the time to explain how the internet has affected mine. Almost everything in my life is thanks to the internet – and even the nearly-forgotten online technology that predated it.

Before I go all the way back, I’ll get the biggest thing out of the way: my three children, who owe their existence to the internet. In 2002, I joined a website called NZ Dating, the purpose of which is right there in the name. It was a time before swiping and social media, but aside from the cheesy early 2000s web aesthetics, it would feel pretty familiar to today’s dating app users: you see profiles, message the fellow singles who attract your attention and then… just hope, I guess?

I was a little introverted and not exactly filled with self-confidence. I’d met a couple of people from the site, but nothing progressed past a couple of dates. So, while I still held out hope for the future, I wasn’t raising my expectations too high. in March 2003, I messaged “melsy” on the site and she replied soon after. The records of our first messages are long since lost, but my vague recollections are of dorky jokes made and returned – we were on the same wavelength!

With our senses of humour a confirmed match, we agreed to go on the only real-world date that was allowed in the early 2000s: meeting at Borders on Queen Street and seeing a movie together. It was Dreamcatcher (her choice) and it sucked, but I told her she smelled good and, thanks to that winning comment (or perhaps in spite of it), she suggested we go to the Easter Show the following weekend. We got on even better in the fresh air and daylight, and just never stopped hanging out together.

Eighteen years later, we’ve been married for almost 15 years and have three children. Not only is this obviously a very significant part of my personal life, but the realities of starting a family also changed my professional priorities. At the end of 2004, with my first kid on the way, I decided my almost-minimum-wage job, working a night shift making reality TV, wasn’t cutting it. So I hustled for another role, and soon I was handing in my notice and heading to a new job, with a better title, more pay and reasonable hours. Since then, my family has remained a key driver in pushing me forward professionally. And, of course, Mel’s support has been instrumental in encouraging me in many endeavours.

If my marriage and kids were the only thing I had to thank the online world for, that would be enough, but it’s so much more significant than that – I can trace so much of my adult life to the early internet and proto-internet technology.

To explain, we need to go back even further, to a time before anyone had heard of the internet. It was early 1992, and I had recently started intermediate school. Like most boys at my school, I wanted cool shoes (“kicks” as the kids today would say, but we just said “basketball shoes”). There were only two acceptable options: Reebok Pumps or Nike Air Jordans.

I had been saving my money and finally had the cash I needed. My dad drove me to Newmarket to buy the Reebok Pumps I’d settled on. But something happened as we headed towards 277 Broadway: we stopped at a computer store. I’d had my own IBM-clone 286 computer since Christmas 1990, and I was always looking for ways to make it do more, such as with the second 5¼ inch floppy drive I’d recently installed.

In the store I saw a modem for sale; a computer expansion card that could slot into the big beige box and let me connect my computer, through the telephone line, to other computer systems around the world (well, around Auckland, anyway). It cost about the same as a pair of Reebok Pumps. I had a choice to make.

I never did end up owning cool shoes.

The modem offered me the opportunity to call into various bulletin board systems (BBSes) around Auckland; remote computers connected to the telephone network, just waiting for users to call in. Each one had its own collection of text-based games, files to download and message boards. Most of these BBSes only had a single phone line, so getting online required persistence, but armed with a print-out of the regularly updated Auckland BBS text file, I would sit at my computer after school and work my way around the various bulletin boards that formed my growing online community.

I formed many online friendships through this community, but one with a fellow geek who went by the name “Amadanon” became especially influential. My online friendship with Amadanon (real name, Jort) grew over the years until, around the beginning of 1994, we met in real life for the first time. He was a few years older than me at the time and had just got his driver’s licence, and he became my conduit to the real-world manifestation of BBSes: the BBS party.

We would hang out on weekends and go to parties filled with socially-awkward nerds in rundown flats in Auckland’s outer suburbs. The parties were a very eclectic mix of people – the obvious techy types, like veteran computer and communications engineers, but also punks, goths, musicians, artists – the only definite commonality was that we were all comfortable using fairly obscure technology to connect online, and then in person. Looking back, it was probably a pretty strange world for a 13 year old to be a part of, but it was the first time I really met “my people”: geeks.

Around the same time, I was not getting on well at my high school, Takapuna Grammar. I had started my educational life being home schooled; since landing in “proper” school at the end of primary school it was never a great fit, but high school was really where the friction started to get too great.

At that stage, half way through third form, the school and I were at loggerheads: mostly we could not see eye-to-eye on homework. I was smart and kept up in class, but it wasn’t enough for them, and I didn’t see why it shouldn’t be. We could not agree to disagree on the matter.

Jort had attended an alternative high school in Auckland’s Mt Eden. Auckland Metropolitan College (Metro to its friends) was established in the late 1970s as part of an experiment in alternative education. It aimed to cater to kids who weren’t fitting into traditional public schools: Metro had been founded based on the Parkway Programme from the US, which embraced the idea that learning can’t be forced; therefore student choice and life experience were to be the cornerstone of school programmes. Students were encouraged to identify and pursue their interests and only gently prodded towards traditional academic subjects.

The school was the first massively transformative part of my life that I could directly trace to the online world, thanks to my friendship with Jort. Prior to meeting him, neither I nor my parents had heard of Metro. But Jort talked it up, and I soon found myself commuting to Mt Eden every morning.

For me, Metro meant the opportunity to experiment with computers, video production and photography in a way that wasn’t possible at my old school. With some encouragement from me and a few other students, the school bought an expensive Mac computer with video editing software, as well as copies of a reasonably new image editing program called Photoshop. I even did some after school, part-time work with my photography teacher making interactive CD-Roms; a bleeding edge technology at the time.

Did I pay much attention to maths? No. Science? Not a whole lot. But the time I spent at Metro exploring the possibilities of computers and video cameras solidified my interest in a career within the film and television industry. That interest was given a further kick when the school facilitated the production of a student-made short film, in which we were let loose to write, shoot and edit whatever film we imagined using professional equipment and with the light-touch mentorship of established industry pros, including film and television director Matt Murphy.

But before I could make the next step towards the television industry, Jort went on to introduce me to what would become my first full-time job at one of New Zealand’s pioneering internet service providers, ihug. I left school and spent the first five years of my working life bouncing between different roles at the company; all the while teaching myself even more IT skills and leaning on my co-workers for programming tips and systems administration tricks.

After leaving ihug, I briefly worked in marketing and communications before heading back to IT as a programmer. But when that role ended in redundancy, I finally remembered the high-school passion that I’d become so distracted from. I quickly fired off an application for film school, which began just a couple of months later.

Years later, having graduated film school and working a little over a decade in New Zealand’s television industry, I saw a Facebook post from another online friend, David Farrier, about a strange tickling competition. The rapidly unfolding collaboration between David and I on that mystery became the feature documentary Tickled.

The investigative work I accomplished with David on Tickled, and on some subsequent collaborations, led me to spend more time investigating little internet mysteries and writing about what I found. Instead of just working on other people’s creative and journalistic projects, I started working to create my own – a development that led, fairly directly, to the role I’m in now.

My decades spending my days online, and my willingness to let the friendships I’ve formed online merge into my real-life, have ultimately come together to where I am now. I’m spending my days researching and writing about various internet rabbit holes, conspiracies and communities, and thinking about all the many ways the internet shapes our real lives, just as it’s shaped mine. It’s easy to get caught up in the negative things the internet throws at us, but I can just stop and look around me from time to time to get a reminder of the endless good it can deliver, too.

I owe a lot to the internet.