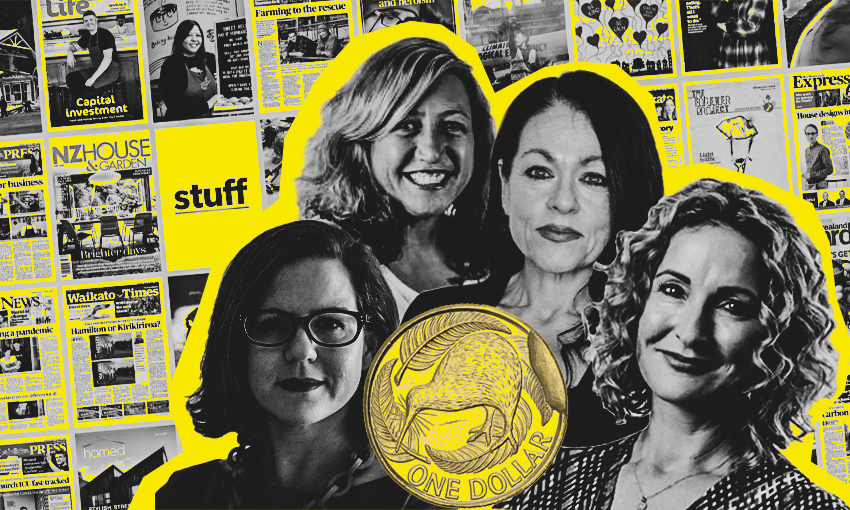

The stakes were existential when Sinead Boucher offered to buy Stuff for $1 in May of 2020. A year on it has completed a remarkable turnaround, says Duncan Greive.

For most of the last decade, Stuff was a paradox: both New Zealand’s largest employer of journalists and a website which seemed to only grudgingly display any pride in its journalism. This was because Stuff was two things which seemed to exist in opposition to one another – one about serving and selling a loyal paying print audience, the other using every trick in the book to generate as many clicks as possible.

Stuff, the company, is a publishing group made up of dozens of metropolitan and regional newspapers. Stuff, the site, is an aggregator of all the news produced from those papers, plus some more from its digital teams. For many years, the site pushed whatever stories were likely to generate the most engagement. The homepage was manifestly optimised for the maximum possible clicks. Each click triggered ad impressions, each ad impression made a tiny amount of money.

It was an era known as clickbait, and almost everyone was doing it – Stuff were just doing it best and hardest. It meant you had to dig deep to find the outstanding journalism the organisation was creating – from the daily news grind to longform investigations, much of which flashed through the homepage, if it made it there at all. The sheer volume at which Stuff produces news meant that a large majority of what it created never saw its homepage, or did so only briefly. And the optimisation model’s bias toward clicks above any other metric meant that a column decrying, say, “Māori special treatment” would look like a hit, regardless of what it did for your relationship with a key audience, or how it made your Māori staff feel.

This had been changing for years, with everything from hiring Ali Mau to run #MeTooNZ to retiring the appalling cartoonist Al Nisbet evidence that Stuff was starting to evolve away from its worst excesses. Yet for all that, no change has come like that over the past year. Since she bought it for $1 last year, CEO and now owner Sinead Boucher has executed one of the fastest and most profound turnarounds in New Zealand business. A couple of weeks back the company celebrated its first year of independence at an event in Auckland. Hosted by a fired up Te Radar, and debuting a new brand feel through a set of hypercolour visuals and text across giant screens, it felt like a celebration of what independence has brought them.

These are 10 key elements which have driven that extraordinary year.

1. All this might never have happened

When Boucher bought Stuff, the company, for less than the price of a single copy of the Timaru Herald last year, it was widely understood as indicating two things. First, that NZME’s attempt to force the government to allow it to buy Stuff had been so poorly received by Nine, Stuff’s Australian owners, that it would rather give it away. Second, that its value had eroded so much that an orderly and clean exit was of greater value to Nine than whatever it might get on the open market.

What has been far less well-covered is just how close the company came to shutting down. At that event in Auckland in early June, Boucher said she had been given word that the decision had been made to follow magazine giant Bauer in winding up the company, “probably the following week”. Thus the purchase was not just bold and brave, but also something which absolutely had to happen. All the jobs and journalism which has followed is built on that decision.

2. Carmen Parahi and Tā Mātou Pono

When Pou Tiaki editor Carmen Parahi was named editorial executive of the year at the Voyager Awards two weeks ago, Stuff staff rose to acknowledge the moment in song. She asked from the stage, “who would have believed that Stuff could get up and sing a waiata Māori at the journalism awards?”

The moment came in tribute to Parahi, who was the driving force behind Tā Mātou Pono, Stuff’s apology to Māori for the way it has covered them historically. It became a deep, often (rightly) uncomfortable dive into their past along with a “hold us accountable” pledge to do better in future. Parahi had assembled an internal group of backers, then made a fateful call to Boucher to pitch the idea. That she got it across the line, and brought so many with her, is a profound testament to her will and skill, and there has been no more deserving winner of that award.

Read more: Leonie Hayden interviews Carmen Parahi

3. Timing is everything

The $1 deal happened during lockdown, with media revenues in freefall and no certainty of outcome. Hindsight reveals this as the perfect time to make the move – both New Zealand and Australia were soon largely out of lockdown’s grip, their economies unexpectedly buoyant. But that Nine were willing to shut Stuff down shows just how tightly fear gripped the media world in that moment, making Boucher’s move even more impressive. Still – so many strange events had to line up to make this possible, proving again that something like luck still plays a profound role in life and business.

4. Emphasising big, statement projects

Tā Mātou Pono is the biggest and most consequential of Stuff’s editorial projects, but there is a long tail geared toward creating impactful journalism. The creation of national correspondent roles has created a pipeline of strong features, and taken back the lead in investigative journalism that was held by the NZ Herald for some time. Stuff has grown a terrific bench of investigative and feature writers, and recruited adroitly along the way, all of which helps lead into…

5. A strong case for reader payments

In the aftermath of the dramatic collapse of Bauer in late March of 2020, all media organisations with reader contributions saw an uplift. Stuff was alone among the big mainstream media in having both a huge digital audience and no ability to directly monetise them. Within a few weeks, that was solved, through the decision to create a PressPatron and push hard for voluntary donations, a la the Guardian. While a paywall would likely be a better strategy given the company’s scope and scale, this model does mesh very well with major projects like Tā Mātou Pono. The reality is that no modern media organisation of any size can survive on advertising alone (on that note: please join The Spinoff Members!), and that media optimised for donations reads very different to that which is optimised to create ad impressions.

6. Concentrating on the core product

For a minute there Stuff flirted with becoming a consumer conglomerate: you could buy internet, power and insurance from Stuff. While that worked to a point, those efforts have largely been sold off or de-emphasised to return to a focus on journalism. This keeps executive eyes on the core product, evident in the rejuvenation of titles like the Sunday Star-Times and Dominion Post, both thriving under new editorial leadership from, respectively, Tracy Watkins and Anna Fifield, who was recruited from the Washington Post in a spectacular coup.

7. The government came through

One increasingly important stakeholder? The government. We’ll never know whether Stuff would have survived the pandemic unscathed without state support, but what we do know is that the wage subsidy, the media support package, the enormous Covid-19 ad spend, and the prospect of the public interest journalism fund all meant the government suddenly played a major role in funding the media.

While journalists and publishers are rightly leery of getting too close to government, when the stakes are existential such support takes on a very different complexion. The key is to hold the line when the fiscal reality changes back, and when bad news breaks. So far, there is no sign of the government’s money impacting the work of Stuff’s journalists – particularly its gallery pack, who remain among the strongest in the country.

8. It’s listening and changing

“All of [Stuff’s] papers were established by settlers, for settlers. That whakapapa has continued right up until this point, and we have maintained that perspective of always protecting the interests of settlers, and now their mokopuna,” Parahi told The Spinoff Ātea’s Leonie Hayden last year. New Zealand journalism has long held the belief that it holds power to account, while often actually reinforcing many stripes of structural power which benefit pākehā, particular pākehā men.

The last decade has seen an accelerating global reckoning, with society and its institutions increasingly coming to terms with their roles in maintaining an ugly and unjust system. For a long time Stuff (like much of our media) seemed like a conservative force, resisting and critiquing attempts to challenge the status quo. Now – in the stories it commissions and the voices it centres – Stuff appears to be listening more closely, and while obviously imperfect, a new direction of travel seems well-established.

Read more: Ali Mau on being harassed and outed in the gossip pages

9. The competition (and its paywall)

The Herald’s hard paywall is at once a very smart and necessary move for its business, and an absolute gift to its key rival. With the core of its best work locked away, only accessible to paying subscribers, Stuff has become the only scale digital news player with all its work freely available to all. So even after famously quitting Facebook, it continues to hold a huge sway over the digital news audience, and thus the national conversation.

10. The pivot to trust

Since becoming owner of Stuff in 2020, CEO Boucher has consistently emphasised trust as the key metric. This represents quite a change – while under Australian ownership, the key word was far more likely to be growth. Trust is an ephemeral quality, though, and while Stuff performed very well at the media awards last month, it also slid out of Colmar Brunton’s most trusted brands survey the week before, after rising the previous two years. It might be a reflection of the fact that telling Tā Mātou Pono, while vital, also resulted in some more conservative subscribers cancelling their subscriptions and viewing the company less favourably as a result.

The pivot to trust over growth is also a reflection that any business with newspapers as its core financial engine is also managing decline in the aggregate. Hard decisions remain in Stuff’s future, and the decline in trust despite an increase in quality shows the complexity of operating media businesses in this era. But a year after it was sold for $1, Stuff is unexpectedly thriving, and showing what can be accomplished in a short space of time when an existential threat is stared down.

Follow Duncan Greive’s NZ media podcast The Fold on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.