Our crack team of film critics return with their latest reports from the Film Festival binge-watch.

NZIFF: Birds of Passage, First Reformed, Disobedience, 3 Faces

The Image Book

“This film is quite weird. Sometimes it’s without subtitles, sometimes it’s without sound. That happens.” It’s rare that NZIFF ushers warn an audience before a film, but it’s rare that any film has as flagrant a disregard for technical standards as The Image Book, Jean-Luc Godard’s broken movie for a broken world. From aspect ratios that shift midway through clips and blown-out images, to sound sputtering across surround channels and extreme pixelation, this post-everything collage is as challenging in form as it is in content. Free-associating the entire history of cinema (from Freaks and La Strada to Salo and Elephant) with ISIS videos, paintings, porn, shots of celluloid being handled and Avid-only-knows what else, Godard weaves a web of allusions – to hands, to cinema as a locomotive, to on-screen coupling as a metaphor for cross-cultural violence – as he winds his way to a consideration of Western depiction of the Arabic world. Combining cryptic allusion with dry Gallic wit – breaking down the onscreen title MONTAGE/INTER/DIT could take paragraphs on its own – The Image Book is a dense, angry, sorrowful, confusing and stunning meditation from an elderly genius deep within his own creative world.

Which, to be fair, sounds perilously close to “crawling up one’s own ass”, and I’m sure many might leave this film feeling that way. But however insular it may get, The Image Book ends with moments of clarity that are impossible to dismiss. While most “political filmmakers” spit out agit-prop for pre-sold audiences, Godard digs unsparingly into our very vocabulary of images. If old revolutionaries are supposed to fade away, someone forgot to give Godard the memo, and bless them for it. / Doug Dillaman

Apostasy

There are well-regarded indie dramas that contain less feeling in their entire running time than Siobhan Finneran can convey in a single expression of repressed anguish. Ivanna, her character in writer-director Daniel Kokotajlo’s Apostasy, comes off as strict and humorless but Finneran’s devastating performance is nuanced and complex, and Ivanna’s core of love for her children is evident beneath her often grim exterior. A pleasing restraint characterises the entire tone of this debut feature about a troubled Mancunian Jehovah’s Witness family. The treatment of fundamentalist groups in cinema tends (understandably) towards the judgmental, leaning heavily upon outsider perspectives, with the groups’ more sensationalist aspects used as ammunition. By contrast, Apostasy broaches the ethical and relational quandaries thrown up by this religion’s more difficult doctrines – forbidding blood transfusions irrespective of whether they might be the only life-saving treatment available; ostracism of members ‘disfellowshipped’ due to ‘transgression’ – wholly from the inside. The gain in empathy comes at no cost in incisiveness. Demonstrative drama is kept on a low boil, but Kokotajlo and company employ a range of creative approaches to exacerbate tension. Long-held close-ups of faces, deft yet simple editing, and a mid-film switch of POV from likable younger sister Alex (a quietly assured Molly Wright) to her much less relatable mother Ivanna, all work to lift what could have been a pedestrian drama into a compellingly fraught, honest-feeling investigation into the workings of this niche community. / Jacob Powell

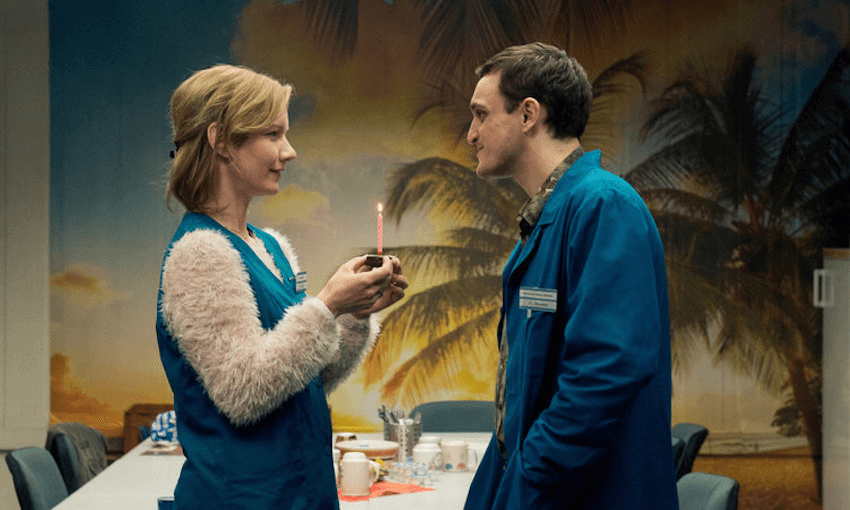

In the Aisles

Opening with a veritable ballet of forklifts criss-crossing darkened supermarkets aisles to Johan Strauss’s ‘The Blue Danube’, director Thomas Stuber signals In the Aisles’ magical realist bent right out of the gate. Muted, yellow-hued lighting in predominantly darkened locales, artfully composed and vignetted frames, smooth camera movement and visual repetitions combine to give the film’s mundane supermarket setting an unexpectedly lyrical quality, similar to that evoked in Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson (2016). This lyricism carries through to the film’s characterisation: when the last customers of the day exit, the floor supervisor swaps the generic store muzak to a JS Bach piece and intones over the tannoy system something akin to “Colleagues! Welcome to the night.”

Franz Rogowski (Germany’s answer to Joaquin Phoenix, also appearing in Christian Petzold’s Transit) lends an unsettled quietude to ‘newbie’ late night shelf-stocker Christian as he learns the ropes and nurses a fast-growing infatuation with co-worker Marion (Toni Erdmann’s Sandra Hüller, giving the role more depth than I suspect was on the page). In the Aisles meanders its way through a pleasing genre blend of deadpan comedy, tragi-romance, and social drama. This movement is mirrored by a cleverly curated soundtrack, which features prominently without being wielded like an emotionally directive bat. Music styles traverse classical, blues, the electronic strains of Son Lux’s ‘Easy’, and back again in an engaging narrative/formal element partnership. / Jacob Powell

Brimstone and Glory

It would be easy for a social issue documentary filmmaker to use Mexico’s fireworks capital, Tultepec, as a symbol for late-model capitalism. Pyrotechnics are both the lifeblood and scourge of the town, with most families having somebody who’s been wounded or killed because of the industry. And yet Tultepec can’t let go of their tradition or their yearly festival celebrating of a mythical past, despite its obvious ongoing harm.

German director Viktor Jakovleski, however, has other plans. Shot over three years of festivals but edited to feel like one week, Brimstone and Glory dispenses with most of the above context after the first five minutes in favour of an immersive sensory experience. Jakovleski brings the full batallion of contemporary documentary camera techniques – GoPros, drones, extreme slow-motion, long motion-controlled tracking shots – along with a percussion-heavy soundtrack that builds both anticipation and tension. With the potential for carnage and the complete disinterest in safety procedures – two stunning head-mounted GoPro shots take viewers high up towers festooned with fireworks, with no safety cables apparent – the sense of possible catastrophe builds (and the occasional actual accident unfolds), but is constantly braided with the swooning beauty of the fireworks themselves. The camera crew seem as blithe to the dangers as the locals, with a finale seeing them embedded like combat photographers as fireworks-laden bull floats (replete with the largest papier-mache scrotums you’ve ever seen) roam the streets of Tultepec. Despite being the least attended screening I’ve been to thus far, Brimstone and Glory received the loudest applause, and deservedly so: it’s a spectacle like no other. / Doug Dillaman