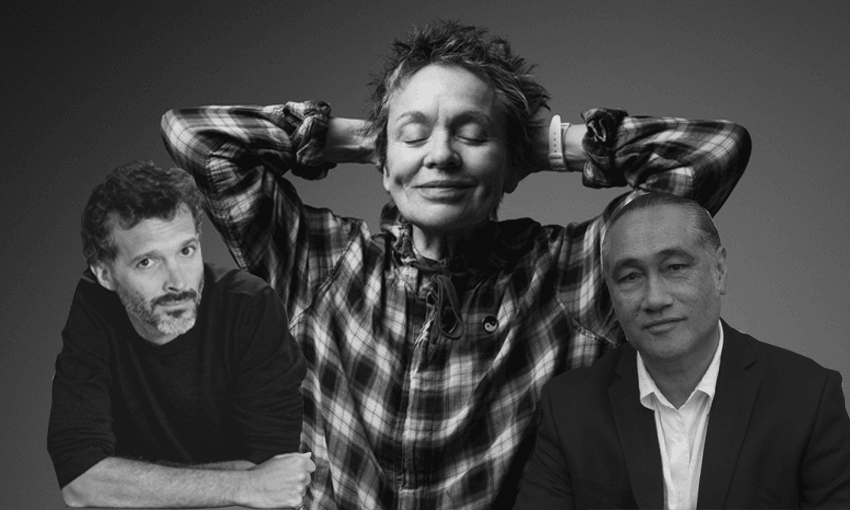

Sam Brooks interviews the three guest curators of the New Zealand Festival of Arts: Bret McKenzie, Laurie Anderson and Lemi Ponifasio.

An Oscar-winning Conchord, the world’s most beloved multimedia artist, and a world-renowned director and choreographer with an attitude. Three weeks, three unique visions of what a festival can and should be.

In 2020, in its 35th year, the New Zealand Festival of the Arts (Te Taurima o Aotearoa) will be handed over to the artists in the service of bringing more artistic voices into the conversation, broadening and brightening the discourse in a way that only a festival can.

These three artists have been invited to curate a week of the festival, each contributing signature selections to the overall programme while giving their week a distinct identity and feel. An arts festival is a platform for extraordinary art, the kind that you often can’t see outside of a festival context. This year, the chance to also be given a degustation of what not just one, but three artists passionately believe in and think that you should see is something that’s rarely done.

I got the opportunity to speak to each of these three guest curators about what they’ve got coming to the festival and what they perceive their role in co-curating the festival to be. Each had a distinct vision for their week, but also a shared understanding of their role in presenting a catalogue that challenges the audience on how they understand art.

LAURIE ANDERSON – Musician and multimedia artist – Week two

When I talk to the curator of the second week of the festival on a Sunday afternoon, I’m nervous. It’s after a few reschedulings, and to be honest, I’m more than a little intimidated. Some of the intimidation comes from having to coordinate an international phone call – she’s calling from her home in New York.

But most of it comes from the fact that it’s Laurie Anderson.

Laurie Anderson is one of those names that your coolest friend goes wild for when it comes up. Not only do they know who she is, but they’ve probably met and partied with her at some point. Arguably the world’s most famous multimedia artist, she’s famous for her eight-minute experimental song ‘O Superman’ that somehow turned into a hit, and her many collaborations with her late husband Lou Reed. This is Anderson’s return to the New Zealand Festival of the Arts after playing the first Festival in 1986.

I needn’t have been intimidated. Anderson’s voice is a blend of gentle and rugged – the sign of a life well lived and well appreciated – and it puts me at rest immediately. It’s a Saturday night for her and she seems almost preternaturally relaxed and, well, cool – an approach she also seems to have towards her week of curating the festival.

“The whole thing is a kind of conversation. I have no idea what’s going to happen, that’s a big thrill to me. Usually I know a little bit or I can guess what would happen, but this time I’m not really sure.”

Of all the artist-curated weeks, it’s Anderson’s that feels like the one that showcases the breadth of an artist’s work. Anderson is a creator or performer in nearly all of the works, with the exception of Lou Reed Drones – a drop-in, provocative sound experience performed by Reed’s guitar technician Stewart Hurwood.

The flagship show of week two is Here Comes the Ocean, a concert performed by Anderson and an ensemble of other musicians, including taonga pūoro composer Horomona Horo.

“Oceans is a combination of songs and pieces that I wrote and that also my husband Lou wrote. It’s sort of strange. It’s a duet in a way, and of course not really because he’s dead, but it’s a kind of a conversation with him.”

The other shows in Anderson’s week include To the Moon, (a virtual reality exhibition at the Dowse Art Museum that’s a collaboration with Hsin-Chien Huang) Concert for Dogs (basically what it says on the joyful, good-boy tin) and The Calling (an improvisational, incantatory performance dedicated to Anderson’s niece, who lost her life in New Zealand a few years ago).

These aren’t things that you’d see in your everyday consumption, even if you were an avid, outgoing patron of art in its many forms. Anderson likes this about festivals – they introduce things to people that they wouldn’t normally see.

“For example, the way music works in New York, it’s very codified. Folks tend to go in groups to see things. They’re opera fans, they’re rock fans, they’re blues fans, they’re experimental fans and they generally don’t mix so much,” she says.

“But a festival gives people the opportunity to say ‘well look, if you can’t afford that $500 for an opera ticket, we’re going to show you operas that have reasonable prices.’ You don’t have to wear opera clothes and go and get a whole new wardrobe to hear that music.

“I think it opens things up for people, and that’s really exciting. Then suddenly, somebody who thought they really hated opera, this 12-year-old grunge guy goes ‘wait a second. My favourite music is Chinese operas.’”

Anderson’s open about the fact that she’s not sure exactly who will come to her events, and seems delightfully calm about that.

“Sometimes I’m very wrong about what people like or I underestimate an audience. For example, there was something recently that I was playing called Songs from the Bardo. This is a very esoteric text and I thought ‘oh, this is really going to be challenging.'”

“The people who came to the show as it turns out, were mostly families. It was sort of like a picnic thing and I thought ‘oh, this is not picnic material. Really. This is really going to be strange’. But I was so completely wrong. People, the families who came, they were amazing. They really listened very carefully and they were very, very responsive.”

Even though it’s the one week of the festival that largely focuses around its curator’s work, it’s also one of the most eclectic – high concept but accessible, collaborative but singular in vision, weird but chill. It’s not at all surprising that Anderson, as both curator of the week and creator of most of the works, has the same approach. As we finish off our phone call, she sums up her vision in her warm voice:

“Hopefully, it’s something that just speaks to people on a very basic level of stories and sounds.”

BRET MCKENZIE – Comedian, actor and composer – Week three

Bret McKenzie needs no introduction. He’s a Conchord, he’s got an Oscar and he’s one of the most famous exports to come out of New Zealand in the 21st century. Which is why I’m alarmed when he’s the one who calls me.

I panic and grab my colleague’s dictaphone and try to find a quiet place to talk as I stutter through greetings and get the recording started. I’m alarmed at how familiar his speaking voice sounds when I’m more familiar hearing his tones backed by guitars (and supported by another distinct Kiwi accent). After the usual pleasantries – it’s a windier-than-usual day in Wellington – we get to talking about his view of the festival.

McKenzie has never curated a festival before and he quickly realised that as a curator, it wasn’t his job to dictate what the work was. He sees his role as facilitator not dictator.

“I prefer it when people just ask me to do what I want to do, so I did that to the artists. I just asked people to do whatever they wanted to do. I didn’t really want to force an agenda onto the people coming to the festival.”

McKenzie comes to the curator job as a Wellingtonian, and someone for whom the festival has been a regular part of the biennial arts diet. It’s from that experience that he hopes to lighten the meaning of what an arts festival can be and attract a new audience.

“Sometimes they can be quite heavy, reading the programme. They’re always really good, but sometimes they seem that they kind of push the audience away. Sometimes arts festivals can be a little highbrow or a little heavy.”

McKenzie’s week is anything but heavy; it’s full of his famous dry humour and wit. And of course a bit of farce and clowning around. There’s Urban Hut Club, a roaming arts treasure hunt along the Kāpiti Coast designed by visual artists Kemi Niko & Co; Släpstick, a mix of clowning glory, music and appropriately, slapstick, from the Netherlands; and a range of late-night gigs including a Sara Brodie-directed concert from Estère and Nadia Reid returning to New Zealand with her new music.

As well as curating week three of the festival, McKenzie also brings one of his own works: a still in progress production of his new musical The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil (adapted from George Saunders’ novella of the same name), commissioned by the UK’s National Theatre and created in collaboration with director Lyndsey Turner and playwright Tim Price.

“It’s a quite surreal political story, loosely about a sort of loser who becomes president of this fictional nation and his brain falls off all the time. So it’s really dark and funny, and I’m really stoked that’s going to be part of the festival.”

It’s also a way for McKenzie to practice one of the other things that he’s preaching for his week of the festival: a chance for artists from across the world to collaborate with each other. The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil has a team comprised of performers and creatives from both the UK and New Zealand, and many of his other shows are also collaborations.

Shades of Shakti is a concert performed by some of Wellington’s finest musicians and sārangī maestro Sangeet Mishra. There’s also a performance from a die-to-see trio: 2019’s most beloved and acclaimed songstress Aldous Harding, indie favourite Weyes Blood and local rising stars Purple Pilgrims.

“I’ve been really lucky with my success overseas and being able to collaborate with people from all over the world. I’ve got so much out of doing that and I’m really stoked that there’s a couple of projects that create that for other local artists. It’ll create a little way to begin relationships for those artists, which I think is really important and special for them.”

McKenzie’s week of the festival sneakily but no doubt intentionally reflects who he is as an artist. It’s a genial, accessible week of work that’s also, on closer investigation, cannily smart. There are some once in a lifetime collaborations to be seen here (I can’t emphasise enough how much of a must-see that trio-concert is) and that’s what makes the festival so special.

Much like Anderson, he sees his ultimate role as connecting audiences to unique experiences.

“With an arts festival, you can’t help but start to think about what art is and what art does. I think the one thing that interests me is the way art can bring people together, so I’m really hopeful that these shows will do that.”

LEMI PONIFASIO – Director and choreographer – Week one

Without a doubt, the person I was most intimidated to meet was Lemi Ponifasio. His CV reads like an ideal travel schedule – he’s staged works at the Avignon Festival (France), the Ruhr Trienelle (Germany), the Venice Biennale (Italy), not to mention countless other festivals around the world. Whenever his work comes to the festival, it’s always been a must-see for me. Nobody makes work like Lemi Ponifasio. It defies form, genre and often description in the best way. God pity the person who has to review one of his works.

Which is why I was surprised to find him an immensely warm, chatty and gregarious man when we met in person in the warm sun of early summer. But then we start talking about art and the festival, the firebrand jumps out. He’s passionate and frustrated.

“What is art in our country? What is our culture? Our society is changing so much with different values, with different races, with different people. How do we prepare cultural infrastructure for that? You can’t just default to the Western image because this image only enhances the prestige of those who are controlling us.”

Our conversation, nearly an hour-long, is full of these sorts of insights – the kind that makes you stop and look at the world from a different angle with better lighting.

He’s conflicted about his role as a curator, or at least, the label of curator. When your work defies and often outright rejects labels, there’s no surprise that you do as well.

“For me, I’m just continuing my work. I don’t even think I’m a curator. I’ve always been the same person doing the same thing, so it’s just happening on a different platform.

“And so they asked me to do that and, of course, I’m very suspicious. But I thought it’s an opportunity for me to place what I’m thinking. It’s urgent right now in such a platform, like the festival, because I’m also a very dissatisfied person with festivals, and how festivals are around the world.”

Talanoa Mau appears to be a direct actioning of that dissatisfaction. It’s a two day gathering where delegations of artists and culture makers from Aotearoa and around the world will give voice to new and unheard ideas, and look critically at what it means to be human in today’s world. The artists invited are a kaleidoscope of the world’s brightest, including raconteur opera director Peter Sellars, author and journalist Chike Frankie Edozien, choreographer Faustin Linyekula, composer and musician Neo Muyanga, and a few of our own shining lights such as Pania Newton, Coco Solid, Dame Anne Salmond and Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal.

“We’ve invited not just the artists, but people who have influence and who are coming from a place of practice. This is not an academic conference where people are just theorising on ideas. These are people who live with these ideas.”

Alongside the conference, Ponifasio is opening the festival with Chosen and Beloved, a live orchestral experience created by him and performed by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. His own award-winning company MAU is premiering their new major work, القدسJerusalem, inspired by the epic Concerto Al Quds by Adonis (Ahi Ahmad Said Esber).

The thing that Ponifasio gets most excited is Te Ata, dubbed as a festival within a festival, taking place in Porirua City. The creative development takes place over the first two weeks of the festival and created with that community alongside artists including US Youth Poet Laureate Kara Jackson, opera singer Jonathan Lemalu and 2019 New Zealand Arts Laureate Jessica Hansell aka Coco Solid. Ponifasio speaks frankly, and bluntly about his philosophy behind the role of the event in empowering a new generation through art. For him, art is about the future being here today.

“These kids are the future, looking at us. They bring in the immediacy of the world that adults are all trying to hide. It’s the same of the artists I’ve invited. These artists are deeply invested and I think they can help us. That’s why I invite them. I don’t care about their work so much. They’re already genius in what they do.”

He’s not wrong about the genius part. Among the artists that are participating in both the conference and the creative development, his week includes two works by international artists, two of the most acclaimed in their fields: opera and dance. One is Kopernikus, a rarely staged opera from Quebecois composer Claude Vivier directed by Peter Sellars, who courts controversy as much as he does rave reviews. The other is In Search of Dinozord, a dance-theatre piece from Faustin Linyekula commissioned by Sellars for the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s ‘Requiem’ that reframes that work through the troubled history of Linyekula’s country, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Our conversation pivots and dives as he talks freely about the state of art in New Zealand and the shopping-trolley approach to programming that a lot of festivals take. Ponifasio wants his programme to be meaningful, to have relevance to our world and the way we perceive it. He wants art to challenge the way we see ourselves.

“The whole point is transformation. If you’re not aiming for that, which is simply the improvement of how you feel about the world or how you see or feel the world, then we’re just part of the distraction. I want art festivals, to speak about art.”

And then, with a gleam in his eye: “I don’t want artists to make a mirror. I want artists to fucking shatter the mirror of society and create new images.”

Over three conversations, each delightful and stirring in their own way, I got three different views and perspectives on what the festival is, and what that festival means to them. Three views that are as different as the weeks they’ve each curated.

It’s no secret that festivals exist as a platform for great art. But with next year’s New Zealand Festival of the Arts, we’ve been given a rare chance to not just see great art, but to view the world through the eyes of three artists who have changed the world, which I don’t say lightly.

‘Icon’ is another word I don’t use lightly. But for just a few weeks in February and March 2020, we have a chance to see the world through the eyes of three icons. It’s a chance to widen our views on what art is, and can be, and for art to smash a few mirrors.

This content was created in paid partnership with the New Zealand Festival of Arts. Learn more about our partnerships here.