Calls are mounting for the government to take a stronger stance in its response to the worsening humanitarian situation in Gaza. But what are its options?

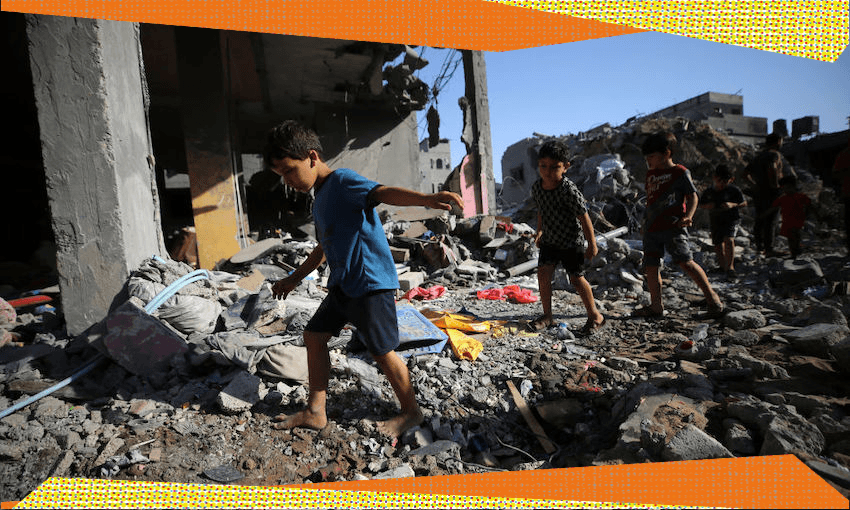

For the past month, social media channels and news outlets have been filled with photographs, videos and testimonies that paint a harrowing picture of the situation in Gaza: entire residential blocks flattened by Israel’s relentless bombing campaign of the besieged strip, children covered in dust and blood being rushed from rubble, rows of dead bodies shrouded in white sheets and inconsolable grieving parents. “This is an avalanche of human suffering that’s 100% man made,” Doctors Without Borders’ Tanya Haj-Hassan told the BBC last week in an interview that was shared widely on social media. “It’s a stain on our collective humanity.”

Israel’s bombardment of Gaza has continued for four weeks in response to Hamas’s October 7 attack in which the militant group killed 1,400 people in Israel, and took 222 hostages, according to Israeli officials. Israeli forces have since killed more than 9,488 people in Gaza, according to Palestinian officials. The supply of basic aid like food, water, fuel and medical supplies to Gaza has been cut off since Israel began its bombing campaign. The question that some are asking in the face of this anguish is whether New Zealand is doing as much as it can in response. And if not, why?

Four weeks of protests in support of Palestine

More than 16,000km away from Gaza, it’s the gulf between the horrors of the worsening humanitarian situation and a perceived lack of action from political leaders that has coloured the mood of recent demonstrations in Aotearoa. Echoing protests around the world, on Saturday thousands gathered across the country in solidarity with Palestine for the fourth weekend in a row. There have been repeated calls for the New Zealand government to demand an immediate ceasefire, as well as long-lasting resolutions to the broader Israel-Palestine conflict which dates back more than a century. Both Te Pāti Māori and the Green Party have backed the call for a ceasefire.

A tempered official response

Underpinning these petitions, protests and posts being shared on social media is the perception that our government needs to take stronger steps to end the war. So what is shaping the government’s response?

Hamas’s October 7 attack occurred just days before our general election. Waikato University law professor Alexander Gillespie believes New Zealand’s response has been coloured by the realities of our transitional political situation, coupled with a desire to not ruffle the feathers of our allies, like the US and UK, who have been outspoken in their unqualified support for Israel.

And for the most part, our leadership has mirrored other western nations’ official response to the ongoing conflict. Since October 7, the response has been largely bipartisan across the two major parties. Both Labour and National leaders immediately and unequivocally condemned the attacks by Hamas and expressed their recognition of “Israel’s right to defend itself”. In outgoing prime minister Chris Hipkins’ initial statement on October 8, he also underscored the government’s concern that the situation could escalate and called for restraint and “the upholding of international humanitarian law by all parties”. Last week, incoming prime minister Chris Luxon once again reiterated support of “Israel’s right to defend itself”, but added that he expected “all parties to act in accordance with international law and demonstrate basic humanity.”

Over the course of this bombardment the government has strayed slightly from New Zealand’s allies by calling for humanitarian pauses and noting the importance of upholding international law. However, neither major party has been willing to condemn Israel’s military response, which has killed thousands, or call for a ceasefire.

The growing call for ceasefire

While there seems to be near unanimous agreement among world leaders that the humanitarian situation in Gaza is intolerable, there’s been vast disagreement over how to break the cycle. Some have called for a “humanitarian pause”, a break in fighting to let aid into the territory, while others have called for a ceasefire, which is considered to be a more permanent solution. Words like “humanitarian truce”, “humanitarian ceasefire” and “a cessation of hostilities” have cropped up too, only adding to confusion.

Just over a week ago, Hipkins and Luxon agreed that New Zealand would vote for a resolution in the United Nations General Assembly calling for a sustained humanitarian truce. It was a notable break from our closest allies, including Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada and Japan, who abstained from voting, and the US, who voted against it.

Locally, outgoing prime minister Chris Hipkins last week told 1News that a ceasefire was not a “realistic prospect” and Luxon has said that the focus at the moment should be on achieving a humanitarian truce. Just days ago, United Nations experts called on Israel’s allies to agree to an immediate humanitarian ceasefire and said time was running out for the Palestinian people, who were at “grave risk of genocide”.

While the calls for the government to demand a ceasefire have grown across the country as they have worldwide, Gillespie advocates what he believes is a pragmatic approach from New Zealand’s leaders. “None of that terminology is that important,” says Gillespie. “What’s important, and the principle that they need to emphasise, is getting humanitarian assistance to two million civilians at a critical time.”

Does New Zealand have any real sway?

New Zealand’s power is limited by the fact that we’re not currently on the UN’s Security Council, which makes binding decisions. On top of that, Gillespie believes there’s a good chance that Israel will not accept a pause, “no matter what you call it”.

Protests have also called on the government to more explicitly condemn Israel’s potential breaches of international human rights law. Rather than rushing to make condemnations, Gillespie argues that the government’s response should push for neutral investigations into potential crimes – such as bombings of hospitals and refugee camps – and stress the general importance of upholding the international rules of law. “No matter which countries and which groups are involved, whether people are or aren’t guilty, we need to echo as loudly as we can that there are rules which are at risk of being broken,” he says.

Has New Zealand done enough?

Robert Patman, international relations professor in the University of Otago’s politics department, sees gaps in our response so far and believes that New Zealand’s independent foreign policy gives the government space to advocate a stronger position on the conflict. “Strangely for a country which I think is deeply committed to fairness, New Zealand has been quite reticent to speak out against measures taken by Israel which are inconsistent with international humanitarian law,” he says.

Though he was impressed by New Zealand’s independent stance calling for a sustained humanitarian truce at the UN General Assembly, Patman believes other opportunities have been missed. “I was a bit surprised that after the New Zealand government said it expected humanitarian law to be observed, that when it became quite apparent it was not being observed and we had almost indiscriminate bombardment of a densely populated area, that we didn’t at least verbally protest.”

While our power to influence on our own is limited, Patman believes New Zealand’s voice is valued among the global community and that we could play a key role in organising with other countries similarly concerned about the situation. This might look like a collective message that “there’s no military solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict” or stressing the “urgent need for a reinvigorated two-state approach”.

“As a small country, we can’t do too much but we can act as a bit of an entrepreneur of ideas,” he says. “It seems to me that one thing New Zealand can do is present itself as the voice of reason.”

Taking a stronger stance undeniably runs the risk of upsetting allies, says Patman, but he questions whether that’s a good enough reason to not follow our own moral compass.

Patman points more broadly to New Zealand’s response to past international situations where human rights abuses were taking place as examples of “where we’ve been prepared to stand up for our principles”. To him, New Zealand’s stance on nuclear security, the 1994 Rwandan genocide (where New Zealand used its position on the Security Council to push for a peacekeeping presence – making it an outlier at the time) and on the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States (where then prime minister Helen Clark criticised the invasion and opposed New Zealand military action in the war) demonstrate this.

“Politics is often the choice between the disagreeable and the intolerable,” says Patman. “You have to work out whether this country should remain comfortably silent while thousands of innocent civilians are killed, or do we risk ruffling a few feathers?”