What compels someone of significant status in society to break the law, repeatedly, might be the same reason I did as a poor teenager.

Update: Further details have been reported that reveal the supermarket in question did not pass a complaint on to police. This article remains, lightly edited, as a commentary on shoplifting and mental health.

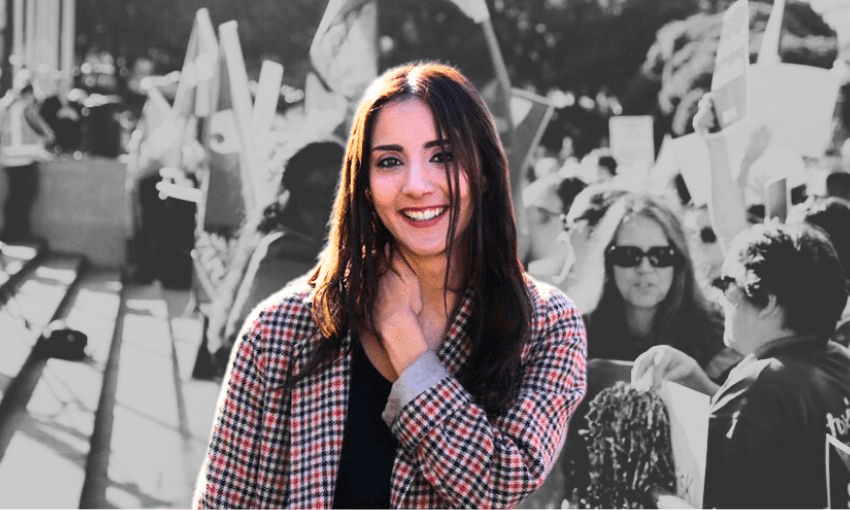

Former Green MP Golriz Ghahraman, who left parliament a year ago today following revelations of shoplifting, is now at the centre of another shoplifting complaint. As reported by Stuff, Ghahraman is under investigation by police for a shoplifting incident at an Auckland Pak’nSave in late 2024, her fifth allegation of stealing. She was convicted on four previous charges in June.

When someone repeatedly does something that they’re not supposed to do – because it is against the law, because they are a former law-maker and lawyer, and because they know better – the typical response is exasperation, akin to wishing your child would just smarten up and learn that bad actions result in bad consequences. Maybe the first response that pops into our heads isn’t “you know what, I think I get why you did that”, because Ghahraman is not supposed to be doing that. But maybe it takes a shoplifter to know a shoplifter.

As a teenager, I stole for many of the same reasons other kids with yet-to-fully-develop brains take five-finger discounts: poor impulse control, the attached thrill and the fact that most of my friends were doing it. But a larger part of this shoplifting was due to having what would be considered a low quality of life: being in a three-person family living in a cramped two-bedroom state home, unpaid bills coupled with empty cupboards, and a general lack of financial stability from living with a solo mother on the dole. Our possessions were secondhand, gifts or nice new things were just about non-existent and for one Christmas, all we got was a single chocolate bar.

Living with limited resources breeds a want to, quite simply, just be like everyone else: a possessor of nice things, and seemingly put-together and stable. In a fucked up way, shoplifting can give you a sense of control, comfort and power purely by finally being in possession of something that represents security, even if it’s a bit of meat from Woolworths – but it’s fucked up, because that comes at the expense of taking something from someone else. In the end though, that still feels better than believing you’re the one whom people are taking from.

Ghahraman, especially at the time of her early crimes, is someone who easily appears to already have it all. As an MP, she was on an annual salary of at least $170,000, and had previously studied at the University of Oxford and worked as a lawyer for the United Nations before life in parliament. On the surface, stealing expensive clothes from expensive retailers when you already have means and status, feels particularly egregious and greedy.

It’s also true that a life of perceived luxury hasn’t always been Ghahraman’s reality. She was famously the first refugee elected to New Zealand’s parliament, having fled with her family from her Iranian hometown, Mashhad, following the Iran-Iraq war to seek political asylum in New Zealand. The war resulted in a million casualties in Iran, and contributed to the displacement of over two million Iranians. When Ghahraman and her family arrived in New Zealand as a nine-year-old, they arrived with only a few small bags; she believed they were just taking a holiday.

“The Islamic regime was in one of its most violent periods in the 1980s when I was born … You see the absolute sea of amputees now in the footage from Palestine, and we were seeing that coming back from the front lines,” Ghahraman told John Campbell in her first sit down interview in 2024. “I have memories of all of that, with big chunks missing as the report [by a clinical psychologist] also acknowledges.” She revealed she had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

As an MP, Ghahraman also received “pretty much continuous” death threats, as well as threats of a physical and sexual nature. In 2019, the intensity of these threats was so great that she required a security escort – online commentary had called to “[hang] her like a lynch mob”. She told Campbell the threats sent her into a fight or flight mode “which you’re meant to be in for a couple of minutes at a time, but I just stayed for six years of it. And you do numb yourself, you do kind of push it down… but it’s gotta come out somewhere.”

Shoplifting is one of the most common crimes in the world, and for many people, a coping mechanism. Ghahraman and I have never got together, braided each other’s hair, and swapped shoplifted items and shoplifting stories. In her own words, shoplifting became an option for Ghahraman because she felt “in crisis”. Coming back to a crowded state house, often with little food and/or no power, made me feel in crisis, too.

Being an MP and being someone living in poverty are two realities that feel worlds away, and conflating my lived experience with Ghahraman’s undermines how uniquely complex both of our situations are. Maybe we could both agree though, that growing from a childhood compromised by cruelty into a successful adult isn’t enough to totally diminish past trauma or our responses to it.

If you grew up feeling like you have no control, and when you’re finally in a position of power, anonymous people are telling you they will take your life, everything must feel somewhat futile. Nicking $9,978 worth of fancy clothing, quite honestly, does seem like the dumbest thing in the world – but at least you look like everyone else you’re interacting with, and at least for a few seconds, there’s a thrill, a sense of power and a way to numb the pain. She says she felt “shame” following her actions, and presumably that shame intensified with a very public conviction. Sometimes those cycles of shame make us revert to the acts that caused us the feeling in the first place.

When we penalise people who commit crimes under distress, that creates another cycle, too. In Aotearoa, 56.5% of people with previous conviction are re-convicted within two years of leaving prison. Recidivism can happen for many reasons, with the most obvious issue being that whatever has caused the person to commit the crime in the first place hasn’t been addressed.

There’s also an inescapable irony in choosing to view Ghahraman’s actions with empathy. The last time I shoplifted, after I was caught by the retailer’s security team, I figured they would call in the police, or worse, my mother. Under fluorescent lights, a very stern guard told me I was too young to mess up my life so they’d spare me a police call, and was sent off with a slap on the wrist. I don’t think many people would have spared a thinkpiece for me.

Editor’s note: due to the level of abuse the writer has received on various platforms, comments have been turned off.