No decision on congestion charging, no cash for clunkers scheme for two years, no political risks taken. Bernard Hickey on the government’s wasted opportunity on climate change.

This article was first published on Bernard Hickey’s newsletter The Kākā.

So much for a climate emergency. The Labour/Green government has unveiled a politically and financially tame Emissions Reduction Plan that offshores a large proportion of our climate spending and backloads most of the costs here to 2024 and beyond.

It has kicked into touch the politically difficult decisions around congestion charges, agricultural emissions and the electricity market. It also chose not to ban the importation of petrol and diesel cars and utes from 2035 nor to shut down connections to the domestic gas network from 2025.

Its flagship “cash for clunkers” scheme isn’t scheduled to start in earnest for at least another two years, with the key decisions on how it will operate, who will be eligible, what types of cars to be exchanged and how much per car it will cost yet to be decided.

What’s in the plan

The ERP includes $2.9b of new spending over four years from a $4.5b Climate Emergency Response Fund (CERF), which is itself funded by revenues from the Emissions Trading Scheme.

However, only $1.17b of that is in the first two years, with most of that used to:

- Subsidise the conversion of industrial coal boilers, mostly in dairy factories ($230m);

- Vaguely fund Waka Kotahi’s efforts to encourage cycling ($373m);

- Subsidise moves to reduce emissions from waste ($100m);

- Pay for research and development to find technologies to reduce agricultural emissions ($92m); and,

- Fill up a past Waka Kotahi funding shortfall caused by low public transport usage during Covid ($47m).

Almost a third of the spending in the first two years is going to help the agriculture sector adjust, even though agriculture has contributed nothing to the current Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) that the spending is coming from, and is not due to be part of the scheme at all until 2025 (the decisions on what form that will take have still not been made.)

Finance minister Grant Robertson said Treasury had advised of an extra $800m in ETS revenues because of higher carbon prices, which offset $840m allocated in December for “international climate finance”, or buying international carbon credits for a market that does not exist yet. Robertson said just $2.9b of the $4.5b fund available had been allocated.

The flagship “cash for clunkers” scheme unveiled in the plan actually only commits $32m to a trial in the first two years for 2,500 vehicles at a cost of $12,800 per vehicle, with decisions yet to made on the remaining $537m to be spent over the following two years. Even so, it would only allow 42,000 clunkers to be traded in for low-emissions vehicles, and only to those households earning less than the median wage.

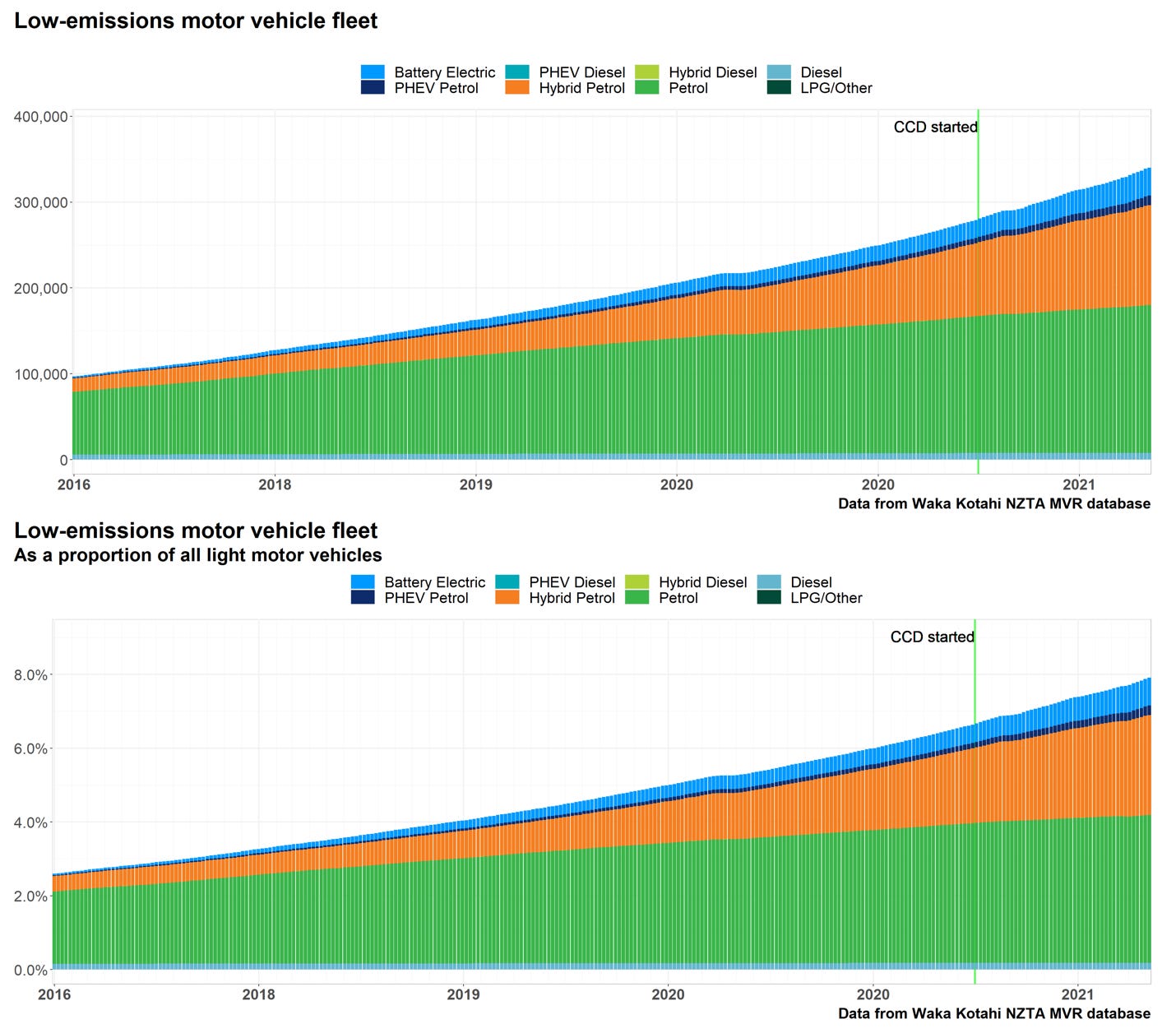

The measures would see just 30% of the light vehicle fleet being electric or hybrid by 2035, with only a 35% reduction in vehicle kilometres travelled. The overall effect of the plan would be to reduce the number of cars on the road by 181,800 by 2035, from a current light vehicle fleet of 4.4m.

The measures to encourage the adoption of electric vehicles and the specific adoption of public transport amount to just $52m of the $2.9b trumpeted. Just $12m is allocated for electric bus purchases, with diesel buses being bought for another three years and still being used until 2037.

What’s not in the plan

The plan was as notable for what was not in it as what was, including:

- No plan to ban imports of petrol and diesel-powered cars by any date, which was recommended by the Climate Commission and widely done overseas;

- A decision not to stop new connections to the domestic gas network from 2025;

- No decisions on congestion charges for Auckland or anywhere else, other than a vague suggestion of more consultation and no action for at least two and a half years;

- No announcement of an extension of the half-price bus, train and ferry fares beyond the current three months;

- No funding for future larger subsidies of public transport to ensure some sort of just transition;

- No significant measures to encourage investment in renewable electricity generation or remove the current one million tonnes of coal currently being fed into Huntly by Genesis Energy to power Auckland; and,

- The assumption about closing the Tiwai Point smelter has been removed from the plan, adding to the burden of moving to 100% renewable electricity and meaning the 30% fall in wholesale electricity prices cannot be relied upon to enable the transition.

My view

The key things to know here are:

- The government had already decided to make its climate spending fiscally neutral, meaning it will only spend the revenues from the ETS;

- It has ruled out borrowing to fund new climate infrastructure or measures to reduce emissions;

- It has also decided to underspend from that fund, effectively tightening fiscal policy by taking in more from the ETS than it is spending;

- Despite being painted as equitable, a full third of the plan’s spending in the first two years goes to the farming sector, who contributed nothing to the ETS, and there is nothing in the first two years to help those on low incomes;

- The government has made no politically painful decisions, kicking the can down the road on congestion charges, road conversions to cycleways, subsidies for electric cars, climate friendly infrastructure and bans on internal combustion engine imports.

The government has done the least it possibly can to meet its limited emissions targets under the Zero Carbon Act, and has done nothing either truly transformational or politically difficult. Its main priority in this plan appears to have been to:

- Reduce government debt now, rather than use the balance sheet to invest for future generations;

- Avoid giving the impression of being “addicted to spending”, as the Opposition has accused Labour of; and,

- Avoid any decision that might alienate or lose the vote of median voters, who mostly live in suburban homes they own and have at least two cars in the driveway – including, possibly, a double cab ute – and who rarely if ever use public transport.

Follow When the Facts Change, Bernard Hickey’s essential weekly guide to the intersection of economics, politics and business on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

Bernard Hickey’s writing here is supported by thousands of individual subscribers to The Kākā, his subscription email newsletter and podcast. You can support his writing by subscribing, for free or as a paid subscriber. There’s a special $30 a year deal for under 30s and a new special $65 a year deal for over 65s who rent and are reliant on NZ Superannuation alone for their income.