The groundbreaking show has had mixed reviews over the past two decades. Madeleine Chapman revisits a classic.

A frequent exercise millennials partake in is to press play on a favourite show or movie from our childhoods only to be shocked by how poorly its aged. When it comes to comedy, the risk of cringing through every racist and homophobic joke is scarily high. And when it comes to bro’Town, there’s no shortage of either. So it was with some trepidation that I pressed play on the first ever episode this weekend exactly 20 years after it first aired.

The review? Plenty of racial stereotypes and lazy gags but still a frontrunner for funniest local show ever made.

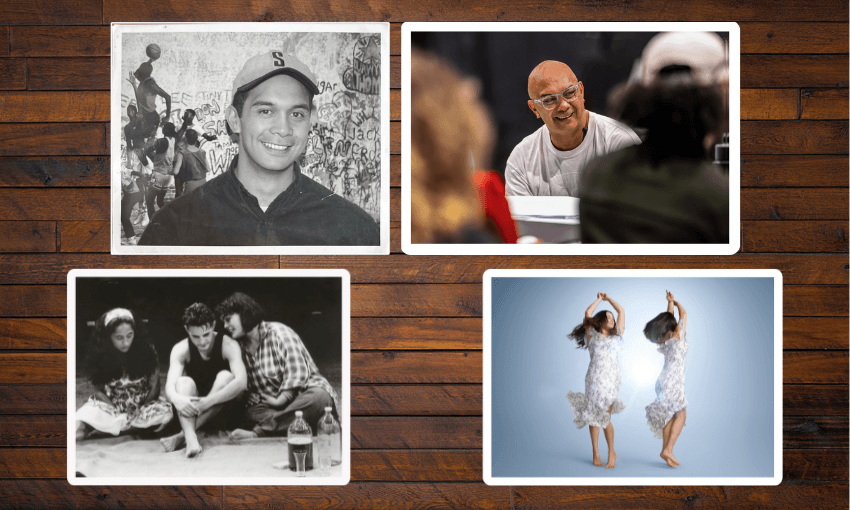

First airing in 2004 and running for five seasons until 2009, bro’Town was the first primetime animated show for New Zealand, airing in the coveted 8pm slot on Wednesday nights. It wasn’t a small investment either – Firehorse Films (run by producer Elizabeth Mitchell) received $1.45m in NZ On Air funding to make the first season with the Naked Samoan, thanks to its lofty aspirations of becoming the local South Park/Simpsons.

It very much achieved that goal, both in its success (it attracted a full third of the viewing audience in its time slot) and in the fact that it received complaints about every single episode in its first season.

I was 10 years old and not allowed to watch TV when the first season aired. I had to go to athletics at the park next door every Wednesday so would run to the park, throw a shot put and run home again to watch each episode on the lowest possible volume and standing with my finger on the power button in case Mum came down the stairs.

Then the next day at school, every brown kid would be reciting the episode line for line, adopting the language until “don’t be racial” stopped being a reference and was just a genuine way to tell someone they’d said something racist.

For Christmas that year I got a bro’Town T-shirt.

It’s easy to think only of the criticisms and misfirings and assume that the show was equally unsophisticated. But as far as social commentary and presenting New Zealand back to itself, what makes bro’Town so jarring to watch now is that it’s almost too realistic, even 20 years on. And its premiere episode is a stunning representation of the whole. I can’t really believe it ever got made.

The Weakest Link

The tone of the show is made clear in its opening scene, set in heaven with Ernest Rutherford, Bob Marley and Sāmoan god (with pe’a) debating the legitimacy of scientology as a religion. I don’t know what was happening in 2004 to inspire the reference but it was equally topical on Sunday when I rewatched the episode.

After the title card, the boys are introduced in quick succession. Mack (effeminate), Vale (dumb, literally), Valea (dumber), Sione (the smart Islander) and Jeff (da Māori). None of these characters are gentle in their representation of classic brown stereotypes, but that’s the point. Today, the caricatures remain. For many Palagi viewers, especially in 2004, those were the only representations of Māori and Pacific people in mainstream media. It’s a perspective within the show that can make or break your viewing experience. If you digest bro’Town believing it’s a display of the creators’ views of different ethnicities and classes, you’ll hate it. If you watch it as a show that takes the white, mainstream views of different minorities and social issues in Aotearoa, and turns them into an uncomfortable – but accurate – caricature, you’ll see the genius in it.

The boys’ dad, Pepelo, is lazy, bigoted and fat, hungry for benefit money. He is ridiculous, but an accurate depiction of what many people think is the norm in brown familites. In fact it was 12 years after bro’Town first aired that some crusty old cartoonists were finally criticised for depicting island families exactly like that (but without the humour). Rather than present a softer, rose-tinted view of themselves, bro’Town instead forced many New Zealanders to confront their own inner thoughts, and it made them uncomfortable. It’s a hard act to pull off, and sometimes the show hit the wrong targets, but what a brave approach.

Jeff da Māori might be a shockingly ashen, snotty-nosed Māori kid with a “mum and eight dads”, but to think he is supposed to represent the show’s take on Māori and Māori struggles would be wilful ignorance. In the first episode alone, perhaps the best and most incisive character is quiz host Robbie Rakete (voiced by Robbie Rakete – the show had an incredible knack for getting every famous person, including then prime minister Helen Clark and even Prince Charles, to voice themselves).

In bro’Town, Rakete is hosting a television show run by Pākehā men. He doesn’t like the boys of St Sylvesters who mostly make fun of him – at one point he yells “bloody immigrants!” in frustration, which made me laugh out loud – but can’t help but want them to succeed. That dynamic, and the clunky execution of Jeff da Māori, is a pretty accurate depiction of the Māori-Pacific dynamic over the years. Always lumped together by Pākehā but with plenty to disagree on between them, and a lot of ignorance from Pacific people (which has come a long way in the past two decades) about the Māori-Crown relationship and Māori as indigenous people.

But where that ignorance can be flinch-inducing in Jeff da Māori moments, the Naked Samoans’ ability to write dialogue that cuts right through the white gaze is second to none. In a clip of Three News, hosted by Carol Hirschfield and John Campbell, the beloved newsreaders put together a classic “low decile school does good” package, except instead of euphemisms, Campbell says the quiet part out loud, referring to St Sylvesters advancing to the quiz finals as “the first really dumb school to win this event”.

When the show producers, drinking a whiskey at the Northern Club, complain about the boys’ success, they ask Rakete to rig the final. He refuses, all morals and staunchness, until they offer him an extra $500,000 and he immediately folds. “Weeelll,” he says, “I suppose the best way to fight the system is from inside so just don’t tell me anything, OK.” Such a line has surely been uttered in boardrooms around the country thousands of times since, and remains one of the best line readings in a long time.

What to leave behind

In saying all of that, the depictions of other New Zealand minorities leaves much to be desired. The early 2000s were a peak for racist Asian jokes, with Pacific people no exception in relishing them. The aboriginal classmate could be edited out entirely and the show would become a lot less racist but otherwise unchanged. In fact, any cultural jokes that fell outside of the creators’ own circles paled in comparison to the nuance and cut-through of their jokes about themselves or about the establishment. A common overexertion of that time in comedy and a belief that if you laugh at yourself you can laugh at others in equal measure.

But despite all the ill-advised attempts to “offend everyone and therefore no one”, the show couldn’t help but be extremely smart writing packaged in the lowest common denominator, with the highest joke-per-minute tally we’ll likely ever see. In a single scene in episode one, Valea wakes up in hospital a genius after being hit by a bus. To test his intelligence, the doctor asks him a series of questions about local history and politics.

In the space of one minute, the show offers a take on:

- hospital staffing shortages (“I get paid by the number of people I treat and send home so we can have the beds”)

- Rogernomics (“an unortuate economic experiment with right wing market reforms which has only increased the gap between the haves and the have-nots”)

- hospital strain again (“If you’ll excuse me I need to go to my other job. Need a cab? I’ll be outside.”)

- Homosexuality (When asked if being a genius means he’s a homo now: “Previously I would have said yes, but now I think homosexuality isn’t a mental illness or a dysfunction but more a normal variation on the human sexuality theme”)

And at the end of the episode, after St Sylvesters win the quiz final thanks to knowledge the boys gained by: watching Sound of Music with a blonde wig on; getting a hiding; being neglected as a child; growing up in a weed house; and hearing their dad complain about losing all his money on the horses, Sāmoan god has a lesson for the kids at home. That “dumbness is in the eye of the beholder” and all that matters is the knowledge you believe to be important.

One of the smartest, and definitely funniest, shows ever produced in New Zealand. If it were made now, it would likely include a more diverse cast of creatives, allowing other funny people from other communities to make their own jokes about themselves. It would be funnier in that sense. But at the same time, it would simply never get made. Certainly not perfect, but when the focus is on the Pacific families and their means of survival in this country, there’s nothing better. Like in episode two when we meet Sione’s scary mum, a character so recognisable it’s almost painful to watch. No other show at no other time could get away with this hilarious (because it’s true) line, yelled by Valea as Sione is being taken home in shame: “Cry on the first hit, they usually stop after that.”

bro’Town always understood its audience and understood that for most Pacific people in New Zealand, humour goes hand in hand with pain. No other local show has illustrated that point so well.