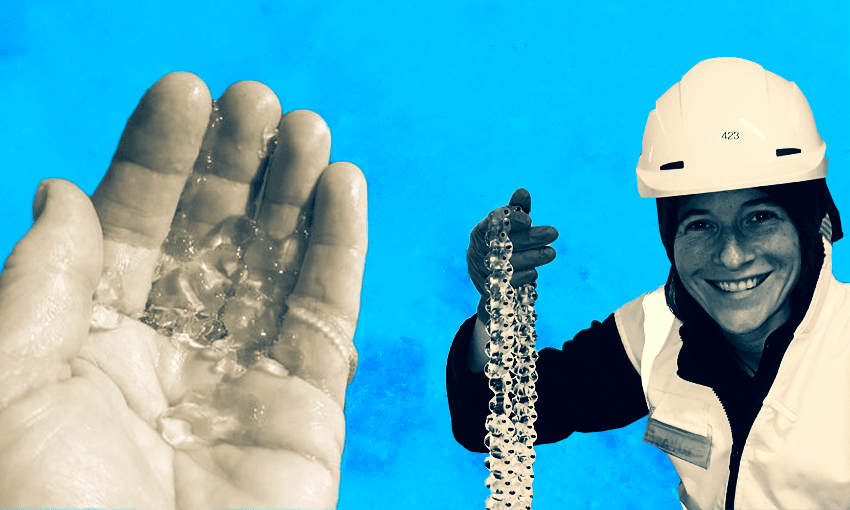

Salps, that’s what – the humble little plankton Emily Writes believes to be our nation’s greatest creature. She talks to a salp expert about the key role they play in our marine ecosystem.

Recently a reader said to me that I’m the only one she knows of who talks about salps. I knew I had to rectify this grave injustice to my favourite plankton by sharing their story with the world.

When I first discovered salps four years ago, I was obsessed. Did you know the largest-known solitary species of salp is called Thetys vagina? I live near a marine reserve where salps are common – often when I’m snorkelling, there are so many that wading through them reminds me of my days on the extreme jelly wrestling circuit.

I am openly a salp enthusiast and all salp enthusiasts know that Dr Moira Décima, assistant professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, is the world authority on salps. To get to interview her is a bit like interviewing a rockstar. She’s the Jane Goodall of planktic tunicate. The Serena Williams of gelatinous zooplankton. I am very grateful she gave her time to answer questions about the best little gender-fluid poop scoopers.

In 2018, Dr Décima led a scientific expedition in New Zealand aboard the NIWA research ship Tangaroa (SalpPOOP expedition – Salp and Particle expOrt Ocean Production). The team looked at the role salp swarms (known as blooms) have on carbon cycling in the ocean (RNZ’s Alison Ballance has an excellent explainer on what they did).

Emily: Hello! I am very excited to be talking to a plankton expert, I didn’t even know that was a thing! Do you have a favourite plankton?

Dr Moira: I have lots of favourite plankton: they used to be krill, but now I really love salps, and pyrosomes!

When I talk about salps, a lot of people think I’m making them up. Like they’re unicorns of the sea, except far less impressive. Salps are real, right? Can you explain what they are?

Salp are definitely real. Of the plankton, they are the most closely related to us – they are in the phylum Urochordata, which is closely related to our phylum Chordata. They are gelatinous, pelagic tunicates. They are closely related to benthic tunicates, what many people might know as “sea squirts”. They have a similar anatomy, with an incoming siphon that pumps water in and one where the water is pumped out. Salps have become modified to live in the plankton, which is why they are clear and almost invisible (can avoid predators). Their siphons are located at opposite ends of their body (which is different from sea squirts) and the water taken in and expulsed helps them swim through the water using jet propulsion. Salps also use this same movement to feed, forcing this water through a feeding mesh that captures most particles in the water. This is why we’ve nicknamed them “the ocean vacuum cleaner”.

Why do we have so many salps in Wellington? Are there salps in other parts of New Zealand?

New Zealand in general has many salps, and they seem to be common on the east coast of Australia as well. We have salps in Wellington, in Goat Island, Kaikōura, Otago peninsula… basically everywhere. The issue is that they are not always there, it takes a combination of oceanographic conditions for them to bloom. Sometimes warm water might bring species down from Australia, other times phytoplankton blooms leads to salp blooms on the east coast of New Zealand. But they are everywhere, just not all the time.

I swim with salps a lot. And I think they have a bad reputation simply because they’re not as majestic as, say, dolphins. But they do more for the environment than dolphins, right? They are actually morally superior to dolphins – is that correct?

Ha, morally superior is a bit of an anthropomorphic view. I would say that all organisms have a role to play in the environment, and dolphins as top predators do as well. At the level of biogeochemistry, affecting carbon transport and other changes in the ocean, salps can have a much greater impact. But food webs need their top predators as well, it keeps them balanced.

But I prefer salps.

So basically, I could start a Swimming with Salps experience and make heaps of money?

I think you should! The problem with such a business is that you won’t be able to predict when and where the salps will be, although we can make some pretty good guesses based on oceanography and on who eats then – that’s how I planned a whole voyage to study them. To me, with their alternation of life stages and forms they are much more interesting than dolphins, but everyone finds different things interesting. Sometimes having background information can make things more interesting as well.

Unrelated, if my child accidentally swallowed six to eight salps while swimming, would that be bad? Is swimming with salps dangerous? Can they swim into any orifices?

Salps are 97% water, sea water. It’s highly unlikely that something bad could happen from swallowing them. If it did, it’d likely be linked to a harmful algal bloom consumed by the salp, and not the salps itself. They are not strong swimmers and they are pretty large, so I think the chance of them swimming into orifices is small.

How can you tell a salp is dead?

It starts to lose transparency and become whitish.

If a salp breaks out of its chain, is it still a salp?

Yes, although many will die after they break out of their chains.

Is a salp sentient?

As all animals, it does feel things. It does not have a “brain”, but rather a more primitive nervous system with ganglia, which means the coordination of these signals is less advanced than in animals that have evolved a brain or central nervous system.

Hypothetically, if my child bought home a large salp in his pocket and made a habitat for it and I explained he shouldn’t ever bring home sea animals and he said he was trying to save it and then we ended up having a pet salp for six months and then I said it had died and we buried it in the garden – could it come back to life? Because someone said they can come back to life and I’m scared?

Salps are actually very fragile. Chances are it will die in your child’s pocket, and if it survives that it will die in your aquarium. They are not meant to really survive out of the ocean, and they are very fragile to being manipulated. No reason to be scared, they can’t come back to life.

I’m glad I’m not going to have a Pet Sematary situation. Anything else you wish people knew about salps?

Their poop feeds the deep ocean! And many fishes that we love to eat in New Zealand – blue warehou, silver warehou – love to eat salps! They play a key role in the New Zealand marine ecosystem because they are reliably present.

Finally, what do we need to do to protect these wonderful creatures?

In terms of protecting salps, we should be protecting the ocean. Salps and many other plankton organisms provide what we call “ecosystem services”, which help maintain the functioning of the planet as know it. Phytoplankton, for example, make 50% of the oxygen we breathe – the other 50% is from land plants like trees.

Salps both help export carbon from the top of the ocean to the deep, increasing the ability of the ocean to absorb the excess of carbon put in through fossil fuel burning, and providing food to the animals that inhabit the deep sea. Salps are also food themselves, as I mentioned earlier, sustaining the tasty fish we like to eat. Protective measures should be implemented for the ocean as a whole, since salps and other short-lived but abundant organisms can’t be protected in the way that large megafauna can. But protecting their environments both protect these organisms and ensure they continue with the ecosystem services that keep the environments we love healthy, and keep our world in balance.