We’re not alone in restricting them to certain sections of the population. But on another important measure Aotearoa is well behind its peers.

With winter approaching in the northern hemisphere my social media feeds are full of people in the USA and Canada off to get their second Covid vaccine booster. They’re getting one of the new bivalent vaccines, rejigged to target either the BA.1 or BA.4/BA.5 Omicron variants as well as the original version of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand, second boosters are available to the severely immunocompromised, people living in aged care and disability care facilities, and people 16 over live who live with a disability, with an at-risk medical condition, with significant or complex health needs, or with multiple comorbidities. Until recently they were also available to people 50 and over, or 30 and over if they work in the health, aged-care, and disability sector. The booster we’re currently using is another dose of the original Pfizer vaccine, rather than one of the newer bivalents. After analysing the data on hospitalisations and deaths during our omicron waves, access to a second booster has just been extended to Māori and Pacific peoples 40 and over. But, as the Manatū Hauora Ministry of Health webpage currently states: “a second booster is not yet needed by younger people who are generally healthy and do not have underlying health conditions. This includes people who are currently healthy and pregnant”.

All that leaves me with two questions. Why have experts in the USA and Canada made second boosters available more widely? And is New Zealand an outlier, or is access to a second booster limited in lots of other countries too?

Is New Zealand an outlier when it comes to access to second boosters?

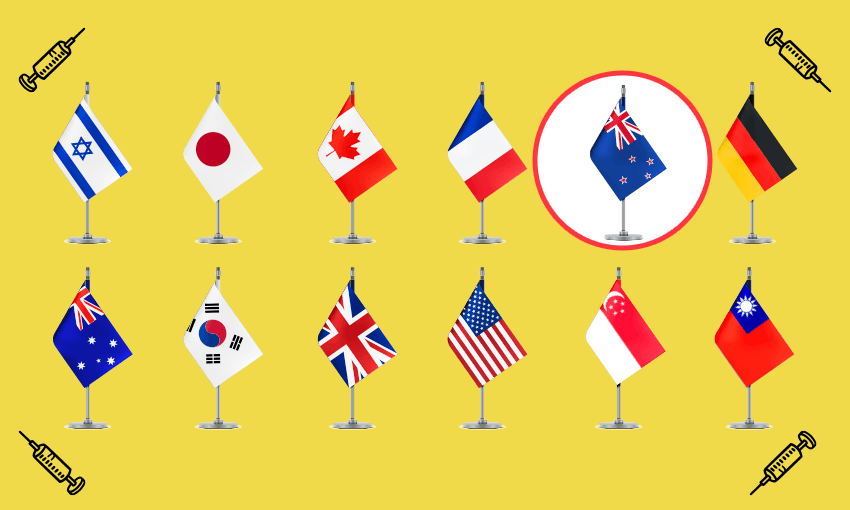

Let’s start with the second question. Are we an outlier when it comes to access to second boosters? To answer that, I turned to Google. Before I show you what I found, I want to put in a brief caveat/disclaimer here. Given there are nearly 200 countries in the world, for the sake of actually finishing this article I limited my search to a small subset of countries. They are the ones I’ve frequently checked our progress against during the pandemic: Canada, France, Germany, Israel, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, the UK, and the USA. I’ve summarised their vaccination policies (at the time of writing…), and New Zealand’s, in the table below. Another small disclaimer: these policies may vary at a state/territory level in those countries where health decisions can be made at that level.

| Country | Vaccinating under 5s? | Second booster? | Bivalent available? |

| Australia | Available for those with certain conditions | Severely immune-compromised; living in a disability care facility; 16+ if living with a disability/at-risk medical condition/complex health needs; 30+ everyone else | Yes (Moderna) |

| Canada | Yes | 12+ (first boosters available to 5+) | Yes (Moderna and Pfizer) |

| France | No | At risk groups; pregnant; 60+ everyone else | Yes (Moderna and Pfizer) |

| Germany | No | 5+ if in at-risk group; those with underlying illness or medical personnel or work in aged care facility, etc; 60+ everyone else | Yes (Moderna and Pfizer) |

| Israel | Yes | At-risk groups; 12+ everyone else | Yes (Pfizer) |

| Japan | No | At-risk groups; 18+ with underlying illness or medical personnel or work in aged care facility, etc; 60+ everyone else | Yes (Moderna and Pfizer) |

| New Zealand | No | Severely immune-compromised; living in a disability care facility; 16+ if living with a disability/at-risk medical condition/complex health needs; 30+ if a health, aged care, or disability sector worker; 40+ if Māori/Pacific peoples; 50+ everyone else | No |

| Singapore | Yes | 18+ if previous dose was 5 months ago | Yes (Moderna and Pfizer) |

| South Korea | No | 18+ if at risk or work/are a patient at a facility with vulnerable people; 50+ everyone else | Yes (Pfizer) |

| Taiwan | Yes | 18+ | Yes (Moderna) |

| UK | No | 5+ high risk or live with someone with a weakened immune system; 16+ a carer or living/working in aged care facility; frontline health/social care worker; pregnant; 50+ everyone else | Yes (Moderna and Pfizer) |

| USA | Yes | 5+ if previous booster was monovalent | Yes (Moderna and Pfizer) |

OK, so when it comes to offering a second booster, New Zealand isn’t an outlier at all. While there are small differences, we’re very much in line with France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, and the UK. I was also curious what different countries are doing in terms of offering Covid vaccines to children under five and again we’re in line with plenty of other countries too. Where we are an outlier is in our lack of access to the bivalent boosters. To be fair, Medsafe only received applications from Pfizer for approval of their bivalent vaccines in the last couple of months, so it’s not Medsafe’s fault we’re behind on that. They still have a process to go through. It does make me wonder whether Pfizer’s lack of urgency to submit a Medsafe application just reflects the fact that we are such a small market and so not a priority.

Why have some countries made second boosters more widely available?

So now we know New Zealand isn’t an outlier in terms of access to second boosters, let’s answer my second question. Why have experts in some countries advised their governments to make boosters more widely available? In Taiwan and Singapore, they’re available for everyone 18 and over. In Israel, it’s 12 and over. And in Canada and the USA, it’s five and over.

I guess the first place to start is with a reminder that each country has convened a group of experts to advise their equivalent of Manatū Hauora Ministry of Health on what their vaccination policy should be. Here in New Zealand, that group is known as the Covid-19 Vaccine Technical Advisory Group, or CV-TAG for short. Groups like CV-TAG are tasked with analysing all the available evidence and then weighing up the potential benefits against any potential harms. They also consider if the potential benefits are worth the resources that will spent to get them or whether those resources would be better off being used on something else. With high inflation and healthcare systems around the world run ragged by the pandemic, we shouldn’t underestimate how influential that last point might be.

Both the US and Canadian experts have made their deliberations publicly available to we can all see what evidence they looked at, and why they believe on balance the benefits of boosting outweigh any potential harms. Before we start looking at the evidence, it’s interesting to see the language the US and Canada are using. They are basically referring to boosters now as “seasonal”, clearly setting the expectation that moving forward a booster for Covid may be needed just like for flu.

OK, back to the evidence. The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) is the group that provides advice to the Public Health Agency of Canada. They’ve stated that the evidence they are looking at relates to the burden of illness, the effectiveness of the original vaccines and whether that immunity is waning, any available animal and human studies on the new bivalent vaccines, as well as the latest evidence on myocarditis and/or pericarditis in relation to the Covid mRNA vaccines. The data includes results from clinical trials in which people had their blood taken after they’d received either the new bivalent vaccines or the older versions and researchers have measured things like their levels of neutralising antibodies. There are also studies, like these from Israel, South Korea, and Canada which have looked at how much second boosters prevented severe illness, hospitalisation, and death. I’m going to come back to this later, as I think what we measure is important.

Both the NACI report, and the report by the US experts (if you’re more of a visual person they’ve put their report up online as a pdf of a slide deck), lay out the knowns and the unknowns. The knowns include things like a fourth dose of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines improving protection against severe disease, hospitalisation, and death in older people, immunocompromised people, and residents of long-term care facilities, as well as the new bivalent boosters triggering high levels of neutralising antibodies both in people who’ve had Covid and those who haven’t. The unknowns of course are things like whether increased levels of neutralising antibodies are actually protective.

One of the things the experts are worried about is whether giving more boosters will lead to lower antibody levels with each new dose – something called immune tolerance. The evidence from the Moderna and Pfizer clinical trials shows this isn’t the case so far.

But the other big worry is the risk of heart inflammation from the vaccines. This is a very rare side effect mainly seen in adolescent and young males. An analysis of all the available evidence by both the US and Canadian experts shows that rates of heart inflammation are lower after a booster dose, compared to after the first two vaccine doses. The data also shows that most people who had developed heart inflammation after being vaccinated had fully recovered at follow-up and reported no impact on their quality of life. The data also shows that the risk of something happening to your heart is as much as five times higher after a Covid infection compared to after vaccination in the group the experts are most concerned about – males in the 12-17 age group.

Taken together, that’s why both groups of experts have decided that the expected benefits of a second booster outweigh the potential harms. Hence the recommendation that boosters be available for almost everyone. Taiwan and Singapore’s experts are being a little bit more risk-averse and limiting boosters to people 18 and over.

There’s more to Covid than the initial infection…

Our CV-TAG and other such groups around the world are taking a much more conservative approach. They seem to have decided that because younger people are less likely to be hospitalised and die from Covid, the benefits of a second booster don’t outweigh the risks. This is where I think its important what we measure when we think about the impacts of a Covid infection. Young people may be less likely to be hospitalised or die, but what about developing long Covid? Might second boosters reduce the risk of that?

There is also growing evidence of people being at increased risk of things like strokes and heart attacks in the weeks and months after catching Covid. Might boosters reduce the risk? Some quite alarming data was recently posted online by the Actuaries Institute’s Covid-19 Mortality Working Group. They’ve analysed Australia latest provisional mortality statistics and calculated excess deaths from a variety of causes. While Covid is currently the third leading cause of death in Australia, deaths from causes other than Covid and respiratory infections are also up. Might these be evidence of the delayed impact of one or more Covid infections?

So, to sum up. Canada, Israel, Taiwan, Singapore, and the US are basically erring on the side of caution in terms of the likely impacts of multiple Covid infections and making second boosters widely available. Meanwhile, we, and places like France, Germany, Japan, and the UK, are taking the opposite approach. Australia is somewhere in between. It’s basically a giant natural experiment and in six months or a year we’ll have more data on which was the right approach.

From all the studies I’ve read about Covid over the last few years, I’d much rather be in the other arm of the experiment than the one New Zealand is currently in.