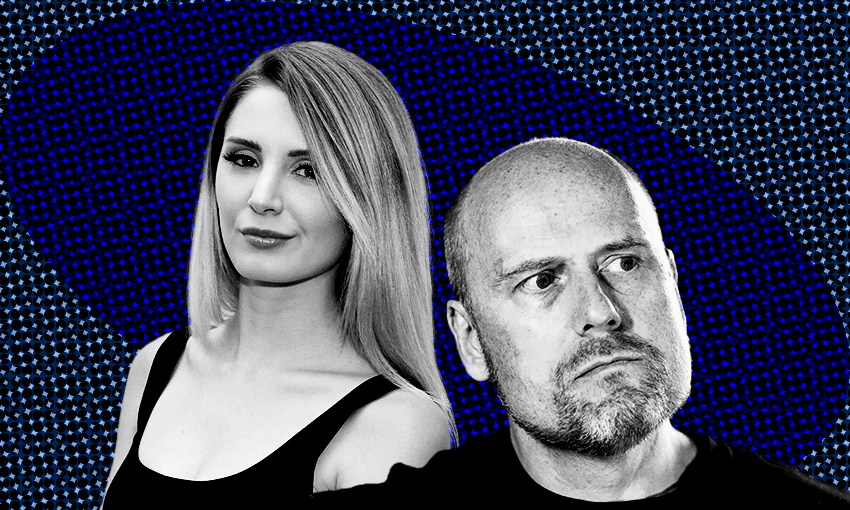

In 2018 Lauren Southern and Stefan Molyneux were sent packing before they could share their wisdom with a paying audience at the Bruce Mason Centre on Auckland’s North Shore. In the name of free speech, was that fair?

Yesterday afternoon, New Zealand’s Supreme Court handed down its decision in Moncrief Spittle v Regional Facilities Auckland, representing the final ripple from the 2018 visit to Aotearoa by Lauren Southern and Stefan Molyneux. At the risk of dragging up some pretty unpleasant memories, here’s a run through of what it all involved.

Who were Southern and Molyneux again?

As I described them in a previous piece, they were two alt-right Canadian grifters busy making money through getting anxious white people to pay them to stoke their fears about their place in a rapidly changing world. Back in the halcyon, innocent age of mid-2018 they rocked up in Auckland with the aim of presenting their travelling road show to anyone prepared to pay their price of admission to the Bruce Mason Centre in Takapuna.

Sounds like an absolutely grand night out (not). Just how terrible was the content on offer?

We’ll never know for certain. Before Southern and Molyneux could share their deeply unpleasant worldviews in Auckland (an indication of its likely content here, with strong trigger warnings for racism), the protest group Auckland Peace Action promised to confront the pair in the streets and blockade entry to their speaking venue. Those promises raised concerns about whether the event could be safely held at the Bruce Mason Centre, which in turn caused Regional Facilities Auckland (RFA) – the Auckland Council-owned company running the venue – to cancel the contract to use it.

Oh dear, what a pity, never mind. But obviously someone did, given that this all ended up in court?

A newly created outfit called the Freeze Peach Cotillion – my apologies, the Free Speech Coalition – decided that it was an outrageous example of Cancel Culture Gone Mad that could not be allowed to stand. This outfit, which subsequently registered as a trade union and changed its name to the Freeze Peach Onion – my apologies, the Free Speech Union – for the absolute LOLs, was headed by one Jordan Williams whom the Court of Appeal has described as having “serious [character] flaws”. It found a couple of convenient individuals prepared to serve as stalking horses and challenged in court the legality of RFA’s decision to cancel the venue hire contract.

Why should I care about any of these people and their shenanigans?

If we must be fair, and I guess we should at least try to be, there is something of a real point of principle involved. All people — even terrible people — have rights and those rights include being able to express their views, as well as the right of others to listen to them (if they want to). Where a public authority – such as the managers of publicly-owned venues – effectively remove such rights, they must provide justification for their actions. Otherwise, we allow those with public power to decide who can and cannot speak in public venues, and that’s a very dangerous path to venture down.

Fine, then, if you’re going to go and get all principled on me. But didn’t RFA have such a justification for their decision?

That really is the crux of the issue. Should the threat of disruptive protest be a sufficient reason for a public authority to (in effect) put an end to expressive activity? Or, does that then create a “hecklers’ veto” whereby those opposed to any given expressive activity can stop it through threatening such disruptive protests? What are the relative obligations of public authorities to protect health and safety, versus their obligations to permit the exercise of fundamental and legislatively guaranteed rights? And, do these calculations shift depending on what the speakers in question want to say, or do public authorities have to be scrupulously “viewpoint neutral” in how they deal with expressive activities?

What did the Supreme Court have to say about all this?

Quite a lot! The Court’s unanimous judgment runs to 137 paragraphs. But, also, not all that much, really. It found that RFA was exercising “public power” when deciding to rent the Bruce Mason Centre, meaning it had a legal duty to respect the expressive rights of those wanting to use it. That’s a good thing, because allowing Councils or other public authorities to escape such legal duties in relation to public spaces simply by setting up commercial companies to manage them would be … undesirable. However, it then held that RFA hadn’t breached its legal duties, because the health and safety issues connected to the potential protests at the venue justified cancelling the event despite the effect on expressive rights. And while RFA could perhaps have followed a tidier process when deciding to cancel the contract for hire, any flaws in how it did so weren’t significant enough to invalidate its decision.

That seems a bit commonsense-y and underwhelming, really.

Indeed. The Supreme Court’s overall approach means that these things will get judged on a case-by-case basis. It rejected a one-size-fits-all approach, such as is seen in the US, where there’s a near absolute duty on public authorities to allow expressive activity to carry on in the face of protests against it. Rather, the relative importance of the expressive activity involved and the risks associated with its exercise must be balanced in each case. And what then really did for the appellants was the event organisers’ decision to advertise the Bruce Mason Center as the venue for the talk without informing RFA about the risk of disruptive protest the speakers’ posed. That then meant that RFA had no real opportunity to manage those risks in an affordable and effective way. Which meant it really was the event organisers’ fault when the contract to hire the venue got cancelled on them.

So, if you want to use a public venue for a controversial event, be open with its management and help them to manage the risks involved?

Pretty much, yep.

Thank heavens that the Free Speech Union fought so hard to have this revolutionary principle recognised in our law.

Indeed. Hope they think that this outcome was worth all the court costs that they will now have to pay to RFA.