For more than a decade, a group of self-motivated ‘Stampers’ has been fighting an insidious enemy in the upper North Island. It’s unclear who, or what, is winning, but they’re not about to give up. Gabi Lardies explains.

In Lloyd Elsmore Park in the east Auckland suburb of Howick, a big, battered red skip is visited by a series of people carrying black rubbish bags, flour sacks and heavy tote bags. From their bags, thousands of lumpy, green, pear-shaped seed pods spill out into the skip.

At Shakespear Regional Park on the Whangaparāoa Peninsula north of Auckland, the local “moth plant lady” spots a great grandmother in a thicket. This moth plant has thick, woody vines. She cuts it, pulls it out from the roots and fishes out its seed pods from the canopy.

On an autumn evening at Bunnings Manukau, an Easter family night is held with crafts and community stalls. One stall has an old-fashioned bird cage full of moth seed pods along with volunteers telling people about the evils of moth plant.

In Hamilton, a volunteer has been knocking on doors in one neighbourhood to offer to remove the weed from gardens. She notices a pattern: when a garden has the weed the occupants are usually renting, so she decides to target property managers, emailing them one-by-one with information on moth plants and how to kill them.

Back in Auckland, on Miro Road in Māngere Bridge, moth plants have flourished among containers at a storage facility. A local asks the business for permission to pull them out. In about two hours on Saturday morning, she and her daughter clear the area.

At 3am, a volunteer lies awake. The sheer quantity of moth plants feels overwhelming. The task of killing them endless. A to-do list of infected sites spirals in their head.

This is the life of a Stamper.

“Rampant”, “cruel”, “smothering”, “noxious”, “poisonous”, “harmful”, “problem” and “irritating” are all commonly used words to describe moth plant (Araujia sericifera) in New Zealand these days, but once it was considered a pretty plant for the garden. In the 1880s, the vine from South America was introduced here as an ornamental, likely admired for its white and pink flowers. By 1888, moth plant had already naturalised and was cropping up in wild and urban areas. Still, seeds were being sold up until the 1970s, for $16.40 a pack, and the plant was promoted as good food for monarch butterflies.

Now, moth plant is an official national pest plant, an official national weed and one of the Department of Conservation’s “dirty dozen”. It is banned from being sold, propagated or distributed, but it’s doing pretty well of its own accord. Those big leathery pods can contain up to 1,000 seeds. Each has a parachute of silky threads and is viable for at least five years. Once they get going, moth plants grow fast. They climb, smother and strangle native trees, block sunlight and take over large areas. Moth plants have a chokehold on the upper North Island, but have been found as far south as Christchurch.

Moth plant haters congregate and organise online, in a 5,000-strong and extremely active Facebook group called Society Totally Against Moth Plant (Stamp). “We are a bunch of randomly accumulated volunteers that live by our own schedules,” says the group’s founder Richard Henty. He is a science teacher based in east Auckland who first learned about moth plant in 2005. The self-confessed acronym lover had formed an environmental group at his school called Women Or Men Becoming Legendary Environmental Saviours – yes, Wombles – and about 200 students had joined. “I thought, what the hell am I going to do with 200 students?” He caught wind that Motuihe Island in the Hauraki Gulf needed volunteers to regenerate bush and began taking the group there on Sundays. When they weren’t planting, they were weeding, and one of the target species was moth plant. Henty began to see it everywhere. “It haunted me every time I saw it.”

He started to remove moth plant as a hobby and got the Wombles helping. But he knew the problem was not one they could tackle alone. In 2012 Facebook was “relatively fresh” and he thought it could be a good way to find people who were also battling against the evil vine. “I started Stamp in the hope of magically finding people. And as it turns out, we didn’t really need much magic. People found us.”

Now, his acronym is a noun and verb. People are Stampers and go out Stamping. Henty describes it as a “pretty gross” and “long-winded” task, though it is still his hobby 20 years since he first learned about the pest. The most unfortunate part of dealing with a moth plant is the white sticky sap it produces when cut. It’s messy and considered poisonous as it can irritate the skin and cause dermatitis. Henty suggests wearing “a lovely pair of long sleeves and long pants that are old and crusty”, gloves and eye glasses. He’s had the misfortune of “goop in the eye” more than once, and says it “sticks your eyelashes together for a day, kind of like PVA glue”.

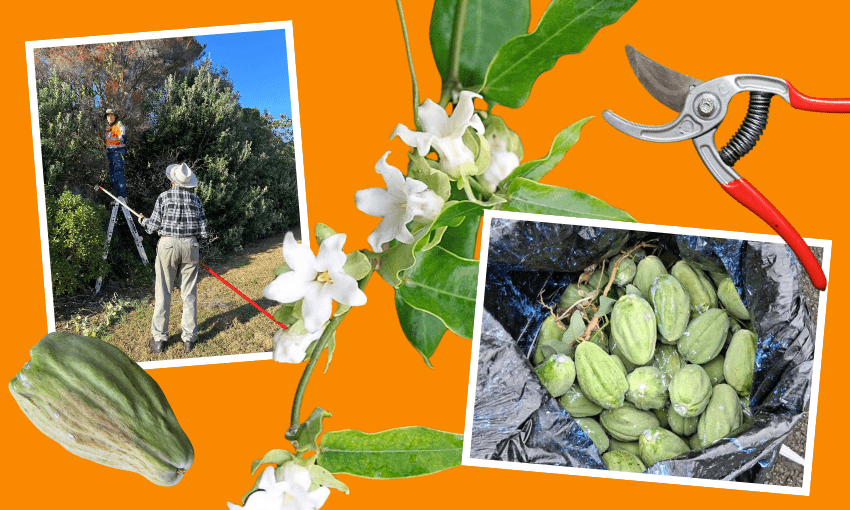

The best way to get rid of a moth plant is to scramble around and find where it’s rooted in the ground, then to pull it right out. This can be tricky as you may see the plant high up in a tree and find it hard to follow the vines to their source. Henty says the second-best option is to cut vines with secateurs and then apply a “blob” of poison. If there are pods, these must be removed, though unfortunately they are often metres out of a normal person’s reach. This does not deter Stampers – most of them have homemade contraptions comprising a long pole with a hook on the end. Henty’s measures six metres and he also has a ladder in the boot of his car.

In some ways, moth plant is an easy weed to remove. You don’t need a chainsaw – a simple pair of secateurs and a small trowel will almost always do the trick. “You can do quite a lot of stuff just walking,” says Henty. “Going for an afternoon stroll you can remove a fair bit of moth plant.” Perseverance is key though – it is not a one-and-done situation. Where there’s a moth plant there are almost certainly more seeds about to burst, so the very best Stampers return to the same locations year after year to keep the green monsters at bay. It’s “quite frustrating”, says Henty. “You kind of wish you could kill it, walk away, never come back.”

Over the years, some structure has sprung up within or alongside Stamp. Sharleen McClay, the coordinator for Pest Free South Auckland, spends about half her year running a moth plant competition, which is supported by local boards. From March to May, teams are encouraged to go podding (collect pods), each counting for a point as long as you take and submit a photo of your haul at the end. Seedlings also count for points. People join as families, friends or groups from schools or early childhood education centres. “We’ve got all these amazing kids and teams out there collecting moth pods,” she says.

Last year, 128,936 pods were collected. This year, McClay has organised for seven 10㎥ skips to be available for competitors to dispose of their pods, and last week, one was filled in a single day. The collected pods will be buried deep in commercial compost where the heat should kill the seeds. There’s no way to deal with pods at home, apart from to seal them in plastic bags and send them off to landfill.

Alongside the competition, Pest Free makes efforts to engage and educate the community. McClay says that now when they have a stall at an event, people no longer mistake the pods for chokos. “The word is spreading – the plant is spreading as well,” she says. Despite the mountains of pods being collected, and the competition being in its fifth year, she says “there’s plenty of pods – we’re at no risk of running out, that’s for sure”.

Between Ōtara and Takanini on the southern motorway, moth plants grip onto the roadside fence. They are covered in pods – but these truly are out of reach for Stampers and competitors, even with their sticks. “No matter how much education we do for people to sort it out in their backyards and neighbourhoods, you’ve then got to also get on board Waka Kotahi for the motorway, New Zealand Rail for along the railway tracks, and then there’s the industrial areas where it tends to just love it and climb all the fences,” says McClay. The lack, or perceived lack, of effort from official organisations is a bitter sticking point for Stampers.

In the case of Auckland Council, David Stejskal, urban forest, arboriculture and ecology manager, says that moth plant is controlled in high-value ecosystems in local parks and reserves. He says that contractors visit areas annually to target vines and seedlings and remove pods, “if present and accessible”. Contractors also respond if moth plant is spotted and reported in maintained reserves. On top of that, moth plant is part of regular management activities in regional parks. In buffer zones around ecologically important parks, council and landowners are responsible for controlling the weed. And, of course, the funding that keeps the moth pod competition ticking can be traced back to local boards and thus the council. Still, Stampers tend to think eradication is preferable over control, and that the contractors aren’t as committed to killing moth plant as they could be.

Despite the years of Stamping and podding, moth plant’s spread does not appear to be letting up. Stampers track it with the help of conservation tech charitable trust EcoNet, using a tool for community-based weed control and data collection. Essentially, the CAMS Weeds Map is an interactive map where people can log viewings of moth plant and their removal activities. When someone reports a location where it’s present, a red dot appears on the map. If a Stamper goes to treat that location, the dot can be changed to yellow. A dot can turn green only when no regrowth occurs. In October, all the green and yellow dots will roll over to purple to prompt volunteers to return and check for regrowth.

Richard Henty, the original Stamper, says the 25,000-ish dots stretch from Kaitaia down to Hawke’s Bay. The task is as daunting as it’s ever been and yet he thinks “we’re making inroads”. In his favourite area of bush, by the Barry Curtis Park creek in Flat Bush, where there are singing grey warblers, crystal-clear water in the stream and the occasional rabbit, he thinks he might be winning. He considers it an annual pilgrimage – one that can take a few days to get through. He remembers that at first many of the large trees were shot through with huge moth plants that he has now killed. “But there’s always plants year after year, so you’ve still got to keep vigilant at it.”