Because we all know someone still waiting on ‘evidence’ about climate change.

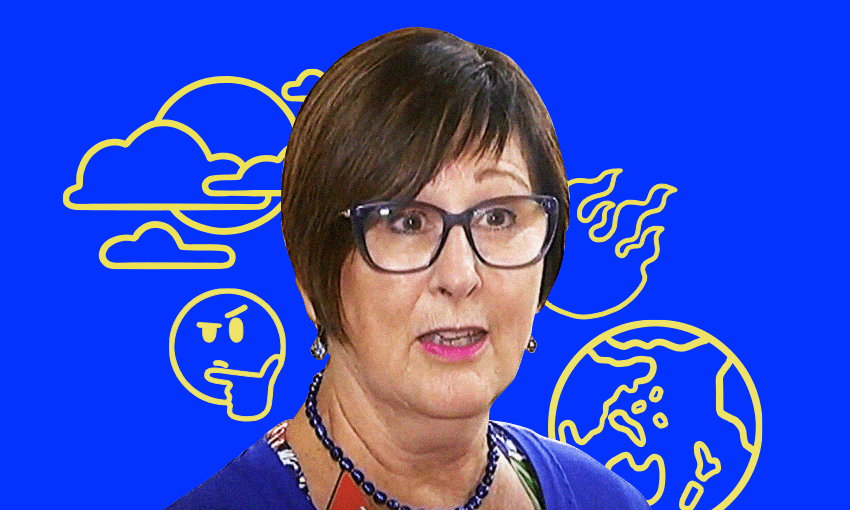

National MP Maureen Pugh began her day on Tuesday by espousing some pretty dodgy takes on climate change. When asked about the correlation between climate change and the impacts of Cyclone Gabrielle, she first said something strange about people in Auckland not pruning their trees and then referred to 2018’s Tropical Cyclones, Fehi and Gita, as “just things that nature throws at us.” Asked if she actually believed in climate change, Pugh said yes.

Things got worse when she was asked about the human impact on climate change. Pugh repeatedly said she was waiting to see “evidence”, as if James Shaw had been nesting on a secret dossier and didn’t want to waste paper photocopying it and sticking it in the internal mail. Pugh then added with a lyrical lilt that “we have cooled and warmed and cooled and warmed over millions of years.” This is where ears pricked up across the nation – who hasn’t heard a member of their extended family mutter that at a barbecue?

“We have an impact, but climate change has been changing for millennia,” Pugh said, doubling down.

Within hours, Pugh was fronting up to media on the cool black and white tiles of parliament with an apology statement that definitely hadn’t been written for her. “I regret that my comments were unclear and would have led some to think that I am questioning the causes of climate change,” she said. “That is clearly not my position. I accept the scientific consensus that human induced climate change is real.” Pugh made this miraculous 180-degree turn in about three hours, and while that’s enough time for 410,958,904 metric tonnes of ice to melt off the world’s glaciers, we’re a bit sceptical.

Unfortunately, just like Maureen Pugh was until Tuesday afternoon, many people remain sceptical about climate change and what is accelerating it. If you have a Maureen Pugh in your life and they don’t have a Christopher Luxon or a Nicola Willis in theirs to supply a reading list, here is a short selection of things to read, watch and listen to share that might help change their mind. If they do it faster than Maureen Pugh, let us know.

The B-B-bloody-C

The BBC’s “What is climate change? A really simple guide” does what it says on the tin. It’s a factual, quick read that has a short, textable summary of what climate change is and why human activity has ramped it up.

NASA’s Vital Signs dashboard

Real time data on the planet’s vital signs from NASA including sea level rise and planetary warming over the last 150 years. A click away is a section labelled “evidence” with a graph that charts atmospheric samples contained in ice cores over the last 800,000 years, succinctly proving that climate change today is not a result of the planet doing its cooling and warming and cooling and warming thang. If your Maureen believes the moon-landing was real and would trust the monitoring provided in hospitals to humans who are ill, this is highly convincing.

This journal article

Get your Maureen a pot noodle and a toga because it is time to go back to uni with this one. “Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming” analysed thousands of research papers examining the causes of global warming, and found that the scientific consensus was clear: “humans are causing recent global warming.” Helpfully, that chimes with the 2,400-page report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change which was summarised and approved by 195 countries.

A human story

If Maureen loves to read, is a fan of autobiography and needs a human lens on this issue, Dave Lowe’s The Alarmist could provide a breakthrough. Lowe sounded the alarm about the climate crisis more than 40 years ago when he began charting atmospheric carbon dioxide above the southern hemisphere. The Alarmist won best first non-fiction book at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards in 2022. This one is particularly good for helping your Maureen understand why some people are quite upset about climate change denial and it’s a cracking read.

Further reading

We asked our terrific books editor Claire Mabey for her best climate change book recommendations and she delivered. The first is Greta Thunberg’s The Climate Book, a collection of over 100 essays by scientists, economists, journalists and historians. One of the essays asks “how can we undo our failures if we cannot admit that we have failed?” Could be good, Maureen! Closer to home Climate Aotearoa edited by Helen Clark “outlines the climate situation as it is now, and as it will be in the years to come.” Finally, if you’re into sleepless nights, The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells will do just the trick.

100 Year Forecast

For Maureens everywhere, we even made our own documentary series back in 2020 looking at the impact of climate change on Aotearoa. The first episode would be a good place to start for your Maureen because it asks the question “how do we know the climate is changing?” and then answers it with what we can only describe as evidence. In just one animated graph, it is extremely easy to see how global temperatures have changed with human-made trends such as the boom in population, the rise of mass production, factory farming, international travel and greenhouse gas emissions. But do watch the whole thing!

Bitches be crying about a carbon tax

Bitches be crying about a lot of things, including whether we should continue to allow scientists to rap, but this two minute tune called “I’m a Climate Scientist” clarifies who we should be listening to on climate change and contains the line “Climate change is caused by people” which is fairly to the point. It’s available to download as a standalone song for the purposes of subliminal influence in the petrol-powered car Maureen is still driving. Released in 2011, it’s twice as old as some of the kids at Granity School on the West Coast whose classrooms could very well fall into the sea because of coastal erosion.

Sir David

If the BBC explainer went down well, you can follow it with a Sir David Attenborough chaser as he explains climate change in six minutes.

TED talks

Maybe your Maureen would prefer to get their climate change information from a nice old trustworthy salt-of-the-earth man named Ted (you don’t need to explain that it actually stands for Technology, Entertainment and Design, we simply don’t have time for that). Pop on a playlist of TED talks for a range of expert-led perspectives on the human impact on climate change, including climate scientist Dr Ilisso Ocko on methane, environmental professor Jaime Toney on why there is so much urgency and climate scientist and author Katharine Hayhoe on why talking about climate change is an essential part of the fight against it.

Climate podcasts

If your Maureen believes the ears are the windows to the facts [citation needed], there are a bunch of very good expert-led climate podcasts out there. Gimlet’s How to Save a Planet sees journalist Alex Blumberg and a “crew of climate nerds” look at the human impact on climate change across every industry from fast fashion to mining. TILClimate is produced by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Environmental Solutions initiative and is now in its fourth season, producing snappy 10 minute episodes across a range of climate change topics.

Talking is also good

As utterly bloody frustrating as it is to still be framing this as a debate in the face of overwhelming evidence, climate change is also frightening and requires change to both adapt to it and try and mitigate it. No matter how accepting you are of the reality we face, most of us would sometimes like to lie under a weighted blanket, watch vintage Attenborough videos of him howling at wolves or the one where a gorilla sticks his bum in Sir’s face and pretend it’s not happening.

If you’re trying to have an entrance level conversation about climate change with your Maureen, don’t go hard on the scientific facts to start. Try an economic or jobs angle. Try personal observations about examples of what climate change is doing in your neck of the woods. It’s more ironic than getting struck by lightning three times when scientists think climate change could be causing more lightning strikes, but we happen to be swimming in those right now.