Clarrie Macklin reviews Dave Lowe’s book The Alarmist: Fifty Years Measuring Climate Change – and explains why, against all odds, it shores him up.

It has been over a year since I finished the two-year-long torment that universities call a master’s degree. My thesis was a trial by ice: I was consumed by Aotearoa’s glaciers and the physics of how they flow. I enjoyed but a single day out on the ice, in Aoraki National Park – my supervisor and I traversed boulders and snow to replace the battery of a lone GPS unit on Haupapa/Tasman Glacier. I loved the adventure; I felt like a real scientist that day. But the rest of my time was spent staring into a screen of lifeless code. My noble quest, from the safe confines of Victoria University, was to build computer models to recreate the flow of Haupapa. The glacier is rapidly retreating, a story that’s echoed across all of Earth’s alpine ice.

Being a glaciologist means coming up against the harsh realities of climate change daily. The anxiety induced by looking at stats on glacial retreat is only made worse when you can’t get your head around your own research. My glacier simulations were constantly crashing and the few that did work showed wildly different flow speeds than what the GPS suggested. With little to no prior experience in glaciology or programming, I was thoroughly out of my depth, drawn on by the idea that we could somehow save the disappearing parts of the world.

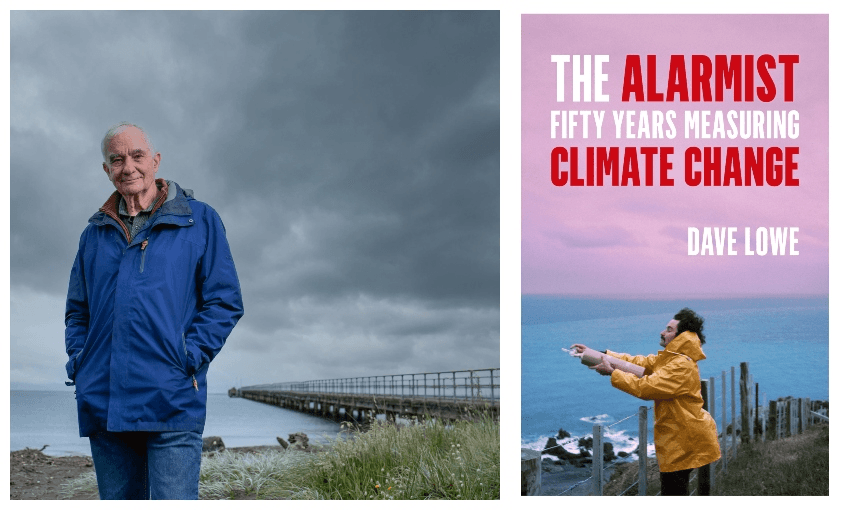

Just as I am beginning to thaw out from the emotional stress, Dave Lowe’s book The Alarmist appears in my life. I’m still fascinated by Earth science, but I’m cautious about coming up against the harsh realities again. An alarmist, a note at the front of the book tells me, is “someone who justifiably raises the alarm about a threat to Earth’s biosphere”. The cover shows Lowe leaning over a number eight-wire fence facing a bitter southerly along Wellington’s south coast. He seems to be in a zen state, holding a flask out to sample Earth’s atmosphere as it whips past. I get the impression he isn’t out to panic me.

Born in New Plymouth in 1946, Lowe is a pioneer of the science underpinning our understanding of the atmosphere’s carbon cycle. He’s devoted his career to researching atmospheric gases and produced a body of work that evidences how human-based emissions upset the balance of Earth’s atmosphere. The Alarmist follows Lowe’s 50-year journey with the atmosphere which has taken him to labs on the California coast, Germany, the Rocky Mountains, on a scientific voyage across the Atlantic, and all the way back home to New Zealand, where he founded a leading atmospheric chemistry group at NIWA. While he has moved on from research, Lowe remains an active educator and advocate on climate change issues.

The book takes me to a time before flash computers and health and safety standards for research fieldwork – a mystical era known as the 1970s. In 1971, on the hills behind the flat I lived in as I wrote my thesis, he took the first measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide in the southern hemisphere, working mostly alone in the barren landscapes of Mākara and Baring Head. This time feels like an era of DIY science. Lowe and his colleagues traversed Wellington’s rugged south coast with equipment they’d built themselves. Spilt mercury shimmered on the floor of a lab where he worked. The scientists of the time had glorious moustaches and windswept hair. Why can’t being a scientist be more like that?

The Alarmist is more than a piece of science history: it’s a memoir, full of humour and enthusiasm, elation and despair. Lowe’s friendships, relationships and struggles are as much a part of this story as the science. There is more than one scene in which he is just having a chat with his scientist mates and mentors, such as Dave Keeling – who, from an observation post in Mauna Loa Island in Hawai‘i, became the first person to observe the trend of increasing atmospheric CO2. (There are a lot of Daves in science, apparently.)

These chats reveal moments of scientific inspiration, yet usually with a beer, chippie bowl, or coffee at hand. This spoke to me. Nearly all of my own breakthroughs with broken glacier simulations occurred away from the computer and in the vicinity of craft beer and Earth Science mates. The science Lowe describes is a monumental achievement; the ordeals he faced as one of the first witnesses of climate change are impressive – I know I’m meant to refer to him as Dr Dave Lowe, but after reading The Alarmist, I feel like he is old mate Dave.

Lowe tells his story as a series of tipping points, moments that shifted his life onto a different path. Many of these tipping points relate to the people he met. As an unhappy teenager, suffering bullying at New Plymouth Boys’ High School – “a hellish experience that imprinted itself forever on my psyche” – he found a mentor in a friend’s dad named Ray. Ray encouraged him to read books, particularly pieces on surfing, the environment, and weather systems. Lowe’s interest quickly grew, taking him through the entire science section at the New Plymouth Public Library, and on to the realisation that he wanted to study science at university. He describes, too, his visceral connection to the Taranaki landscape he grew up in, which led him to a love of surfing. “As a young surfer and ever since, I’ve tuned in to the atmosphere,” Lowe writes. “Watching its changing moods is a rewarding and spiritual experience.” There is a sense in which surfing was formative in his understanding of Earth as precious and finite. The surfboard was a meeting place between the atmosphere, the ocean, and himself.

These tipping points in Lowe’s early life occur shortly after he turns 15 when, “after three years of misery and failure”, he promptly drops out of school. Skiving off to surf, read, and meet new people turn out to be the most useful initial steps in becoming a world-leading scientist. Lowe returns to the same school with a spark. He is determined on getting university entrance and studying earth sciences. He cracks on, even though his hesitant teachers view him as a boy of “broken schooling” – yet, this boy goes on to receive the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his work as a lead author of the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report on climate change. At the time, this report was the most trusted and transparent scientific document on the topic, influencing policymakers and shifting the world towards action against the crisis facing us. Reading about Lowe’s experiences left me wondering how many brilliant kids have fallen through the cracks, without the right inspiring teachers, like Ray, to set them on their quests.

It amazes me to read about Lowe chatting to people about climate issues at student parties in the 1960s and 70s. In murky student flats on our somewhat remote Pacific island, he talked about what would eventually become the most discussed environmental catastrophe to face humankind. Yet, when he brings up carbon in the atmosphere, people simply have no idea what he’s on about.

In 2018, when I was doing my thesis, people knew exactly what I was talking about. At parties, my glacier chats earned me the title of Ice Man, Mr Ice Cold, or simply Dr Freeze. People would ask, “Hey, how are those glaciers doing?” To which I’d say, “Aw, yeah, a bit melty, actually.” “Oh. How fucked are we?” they’d ask, casually anticipating Earth’s collapse. “Not sure exactly,” I’d say, “but we may as well drink up and get lit while we still can.” It has always been hard to come up with messages of hope from inside a field of science where the destruction of Earth’s ice is at the centre of the story.

It strikes me that Lowe, while very forthright about our climate crisis, does not dwell on the more depressing facts. His humour and interactions with people pull the story forward, which I found particularly useful in navigating his account of PhD study in Germany. He had a shocker of a project. First, Lowe uprooted his life in New Zealand for the bitterly cold, bland city of Jülich which was pervaded by smog and a smell “like beetroot being boiled” (a comical misfortune owing to the nearby sugar beet processing plants). His work focused on the life cycle of methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas of which human-created sources include fossil fuel processing, landfills, and agriculture. Lowe’s target: formaldehyde, a chemical that marks the reaction of methane with the atmosphere. However, at that time formaldehyde in the atmosphere had a concentration of around 0.2 parts per billion (about a million times lower than atmospheric CO2 concentration) and no established technique existed to detect it in background air at different heights. After several months of experiments and equipment not working, Lowe reached another low point. Reading this triggered my uni stress, but Lowe’s blunder trying to buy beer, owing to clumsiness with the German language, and being called a “Doofer Sack” (stupid sack) had me chuckling enough to read on. Eventually, despite the odds, Lowe cracks the problem, successfully measures formaldehyde, learns German and defends his PhD speaking it.

Science is relentlessly difficult. Things not working out can create a large personal toll. A month from my thesis hand-in, I still had no results. I was trying to figure out how large rainfall events relate to massive accelerations in glacier speed. We measured GPS positions on the glacier surface within a three-hour window, and calculated speed. During one rainstorm, Haupapa/Tasman Glacier accelerated by over 20 times the background rate. I ran countless experiments on my computer, controlling water pressure beneath the glacier to recreate observations. Ninety-nine percent of my models crashed, which was heartbreaking because they usually had to run overnight. One model broke the sound barrier. The most frustrating part was knowing it was impossible to see what was going wrong. My computer was a black box that worked or failed on its own terms. Likewise, we had no way to put equipment beneath Tasman Glacier to see how water interacted with the hidden ice that slides across the basement rock. The secrets were literally in the dark.

I spent the last month of my thesis frantically running glacier models. I limped around the dimly lit corridors at night after having a wart removed from my feet. I fell ill and wrote up my results and my theory in a delirium. I drank coffee through the night and survived on meagre meals of Weetbix, peanut butter, and Domino’s. It was an isolating, soul-breaking experience, but in my haze, I somehow managed to pull some scientific findings from the darkness.

Lowe’s story shows me there is light in the bleakest reaches of scientific research, and life. He reminds us that cherished research can be destroyed, that cold hard facts can nullify scientific theories, that new approaches must be taken. Like the measuring equipment at Baring Head that often broke and had to be repaired, Lowe had to rebuild himself after years of working long into the nights, after separation from his first wife, after disconnection from friends. In his darkest hour, help comes from an unlikely friendship with an elderly couple. They take him in, listen to him. This gives Lowe hope and a chance to rebuild, and the motive to step back from his work. It was the act of stepping back from science and going on a rollicking OE in Europe that allowed him to gather himself and go on to create the body of work he is now known for – it shows how important people are in the scientific process. Even scientists (especially climate scientists, I think) need a shoulder to cry on for support in those bleakest hours.

By the turn of the century, Lowe had been watching atmospheric carbon increase for 30 years. He’d had to bear the brunt of sceptics, climate change deniers, and indifferent politicians. He had published paper after paper. Raw anger is evident in his writing, particularly towards the end of the book. In his author’s note, he says that he resisted the idea of calling himself an “alarmist”, because of the stigma attached to this term, but that now he describes himself as one – because the alarm is justified. In 1970, when he first began measuring atmospheric CO2, levels were at 321 parts per million (ppm), with a growth rate of 1 ppm per year. “Today, in 2021, the latest atmospheric CO2 measurements from Baring Head are more than 410 ppm with a growth rate of over 2 ppm per year,” he writes. A whole atmosphere has changed in his sight.

The stakes are so high and it sometimes feels like the science world can barely keep up with the rate of change. As a young scientist in glaciology, I felt my studies carried a sense of duty. I remember asking my supervisor about a coding problem I was having. I showed him the troublesome code and he said, “Uhhh, I don’t know – I think you know more about this glacier modelling software than I do.” “Shit,” I thought, “I’m the expert.” It was a horrifying moment. If I didn’t model these glaciers, who would? I felt the weight of the world’s glaciers collapsing on my back, and those deadlines in UN reports – cutting emissions by 2030, carbon zero by 2050 – inching nearer.

I think of my thesis, neatly bound and sitting on my parents’ coffee table. After I finished it, I asked my mum what she thought of it. “I read the first chapter. Pretty bloody depressing, to be honest,” she said, or something to that effect. I saw a sadness in her face that I had learned to numb myself to during my studies. My Mum is smart – she’s a wicked poet and a brilliant career counsellor, which comes in handy for my bi-monthly career crises – but I don’t expect her, or anyone, to read through my 200 pages of incomprehensible equations, parameters, and jargon-infused discussions.

In The Alarmist, however, I learned a lot about atmospheric chemistry while reading a thumping good story about a life in science. Lowe writes beyond disheartening scientific facts and puts the process of learning into the voice of a kind but feisty New Zealand science elder. And after reading his book, I managed to look at my thesis without crying, sighing, or assuming a foetal position on the floor. In fact, I looked through it with renewed interest.

Lowe’s book left me with a dire warning for the future if we do not act. Yet, he does more than just raise the alarm: he also shows us the people around him on his journey through atmospheric science. I thought of my partner who supported me through the bleakest hours of my climate science journey. I remember unloading my glacier worries on her during one of our first dates as we walked to a BYO. “It just feels like the impact of my work is so intangible,” I said. “I just don’t feel like doing all of this work is helping.” She said something along the lines of, “It’s just a drop in a pool of knowledge, but you’ll never know what your research might lead to.” It made me feel better.

The Alarmist: Fifty Years Measuring Climate Change, by Dave Lowe (Victoria University Press, $40) is available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.