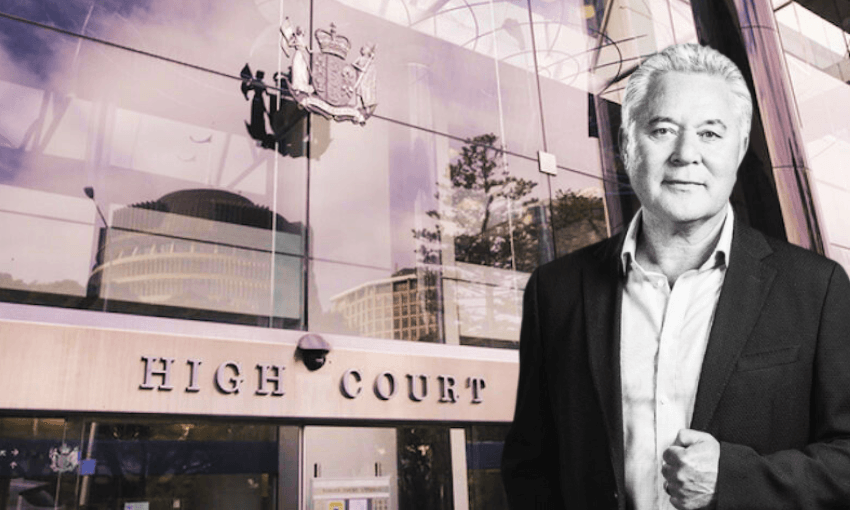

Lawyers acting for the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency chief executive have appeared in Wellington High Court to argue for a judicial review of the decision to award the North Island contract to another provider. Lyric Waiwiri-Smith reports.

John Tamihere’s challenge to the procurement process that saw his commissioning agency lose out on a long-held Whānau Ora contract is a case of concern over “major disruptions to services”, not the grumblings of a “disappointed commercial partner”, his lawyer told Wellington’s High Court on Tuesday morning.

Less than a month after Tamihere’s Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency (WOCA) was told it had lost out on receiving a part of Whānau Ora’s $155m commissioning contract, lawyers for the agency (formerly known as Te Pou Matakana) filed urgent documents in the court on Friday last week requesting a judicial review. Secretary for Māori development Dave Samuels and his ministry Te Puni Kōkiri, the agency responsible for Whānau Ora contracts, were named as the first and second defendants, alongside new contractor Ngāti Toa as the third.

WOCA was one of three providers, alongside Te Pūtahitanga o Te Waipounamu and Pasifika Futures, which had held a Whānau Ora contract since 2014. All three lost their contracts after changes to the procurement process saw the number of commissioned agencies increase from three to four, with services in the North Island to be split into two and locally focused, though WOCA’s lawyers claim the “vast shift” in the system was designed to ensure it would not be eligible for the next round of contracts.

Wendy Aldred KC, representing WOCA, asked the court to consider the contextual issues within the case, arguing her client was not simply a scorned former contractor, but a service whose evidence of reach and success had been overlooked. WOCA was “not just simply a funding vehicle”, Aldred said, but a “network of 113 service providers, providing crucial services to some of Aotearoa’s most deprived areas and most vulnerable whānau”.

“This is a contextual call for the court to make,” Aldred said, though Justice Boldt requested further clarification on what this context might be. “If this was a company like Spark seeking to put out a procurement process, you wouldn’t think that the outcome of that would be judicially reviewable either,” Justice Boldt said.

Aldred drew on a 1,601-page affidavit filed by Maria Halligan, director of funding and contracting at Te Whānau o Waipareira, a subsidiary of WOCA, which included a history of the Whānau Ora contracts. Halligan included a 2010 Whānau Ora taskforce report, which recommended Whānau Ora be te ao Māori-led, to recognise the position of Māori in Aotearoa and te Tiriti o Waitangi.

A separate affidavit filed by Tamihere also covered a history of working with Whānau Ora, and evidence of WOCA’s success in reaching and supporting communities in need. Tamihere had highlighted the vulnerability of those his service supported, whānau who he wrote are “in for a very long winter because of the immediacy of this disruption”.

“So, the plaintiff argues that this is a classic exposition of the first defendant answering or meeting an obligation under Article 2 of the Treaty,” Aldred said. But, Justice Boldt pointed out, the contractors who have replaced WOCA are also Māori.

“You would have a case if the government said, ‘building on the success of our school lunches programmes, we’re contracting this out to Serco … we don’t need to be culturally relevant,” Justice Boldt said. “What we’ve got here are competing providers, all of them – as far as I can see – steeped in te ao Māori, and a decision by the ministry simply to prefer different ones.”

Aldred said the plaintiff had “no allegation of bad faith at this stage”, and preferred to see an application for interim relief progressed to halt Te Puni Kōkiri’s new contracts, which are supposed to come into effect on June 3. She offered that the plaintiff would be willing to foot the bill for financial damages lost as a result, an offer described by the defendant’s lawyer, Tim Smith, as “spectacularly naive”.

“What we’re talking about here is a competitive process, and you’re not happy with the result,” Smith told the plaintiff. He offered to Justice Boldt that Aldred’s position in broadening the commercial contexts of the case clouded the core matter, which is that “as you rightly said, all of the respondents in this context are Māori providers with excellent credentials”.

Smith told the court that if orders were granted in this context, it would only be “stopping the horse that has already started to run”. WOCA’s case hinged on the idea of a status quo not being upheld, Smith said, but the status quo was now the fact that WOCA was no longer the incumbent.

“Let’s just be honest about what’s going on: the main beneficiary of that is the applicant … it can’t be for the benefit of those downstream,” Smith said.

Justice Boldt said the weakest part of the plaintiff’s case, even if accepting the wider context brought forward by Aldred, was that the challenge “simply reverts back to ‘we are the best provider for these services, and why could anyone have chosen not to continue with us?’”

“All the arguments run by my learned friend are fundamentally flawed,” Smith responded.

“You’d be throwing a spanner in the works of a major policy rollout for the benefit of some of New Zealand’s most vulnerable people.”

The case will return to the Wellington High Court on Thursday.